|

Isaac Henry Tate By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. Isaac H. Tate in the Civil War, Part Two: 1863 On April 1, 1863, after he had regained his health, eighteen-year-old Isaac Tate said goodbye to his family in Alabama and went to Columbus, Georgia, which lay just across the Chattahoochee River, and enlisted in the Confederate Army again, this time for the duration of the war as a private in Company A, Fifteenth Alabama Infantry-the very same unit to which his brother James was then attached. Isaac and any other new recruits were then sent north from Georgia, probably by train, to Virginia, where the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment was then serving as part of the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Gen. Robert E. Lee. In the spring of 1863 the Fifteenth Alabama, which had previously been part of Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson's Division and already seen some hard fighting in a number of battles, was assigned to Gen. James Longstreet's First Corps, which consisted of three divisions commanded by Gen. Lafayette McLaws, Gen. George Pickett, and Gen. John Bell Hood of Texas. Hood's Division, to which the Fifteenth Alabama belonged, was subdivided into four brigades led by Gen. Evander M. Law, Gen. Jerome B. Robertson, Gen. Richard H. Anderson, and Gen. Henry L. Benning. The Fourth, Fifteenth, 4Fourth, 47th, and 48th Alabama regiments made up Law's brigade. Thus the chain of command for the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment was General Lee, then General Longstreet, then General Hood, then General Law, and then finally, their own Col. James Canty. Company A, also known as the "Canty Rifles," to which young Isaac Tate and his brother James were attached, was led by Major Alexander A. Lowther, who had succeeded the company's original captain, James Canty, a prominent Russell County planter, after Canty was advanced to the rank of colonel. Lowther, who "had seen service in Mexico, and for this reason was believed to be well qualified to command a skirmish company" such as Company A, which was "armed with Mississippi rifles," was then afterward promoted from captain to major. This was an unusual situation because lower ranking captains usually led companies, not majors. Later, on August 14, 1862, Captain Francis K. Shaaf succeeded Lowther in command of Company A.

In all likelihood, young Isaac H. Tate reported for duty with his regiment just in time to take part in the unsuccessful siege of Suffolk, Virginia, which began on April 11, 1863 and continued through April 30 when General Longstreet "received orders from Lee to join him at Fredericksburg as soon as possible." Longstreet, reluctant to abandon a foraging party that was then "miles away on the coast, gathering supplies," sent a message to his commanding officer, asking if he could wait until the foragers returned. On May 1, Lee sent another urgent order, to which Longstreet replied in a similar fashion. In the meantime, federal troops attacked Longstreet's corps, "in a heavy and protracted skirmish, which continued nearly all day," resulting in "several casualties." For a description of this skirmish, we turn to the reminiscences of Pvt. William C. Jordan, of the Fifteen Alabama Regiment's Company B:

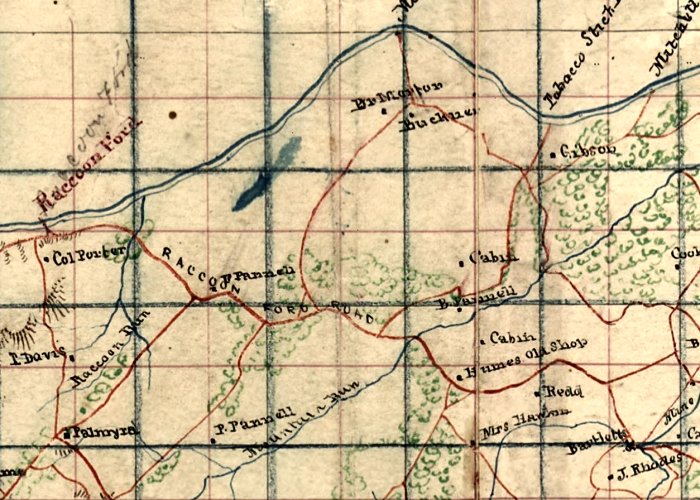

On May 4, according to Col. William C. Oates, who commanded the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment for almost all the entire time that Pvt. Isaac H. Tate served in it, Longstreet's troops, who were then "more than one hundred and fifty miles from Fredericksburg, finally began to move, marching rapidly for "part of the way" and traveling "by railroad a part." On May 5, after passing through Richmond, they reached a plantation called White Hall, "about midway between Richmond and Fredericksburg" wrote Oates, located near Walkerton (then called "Walker Town"), located just south of the Mattapony River in King and Queen County. There, they received the news "that [Union General] Hooker had been beaten by Lee and had recrossed the Rappahannock." The men of the Fifteenth Alabama also learned to their dismay that "the immortal Stonewall Jackson" had been "mortally wounded, which made it a dearly bought victory for the Confederacy." Oates, whose postwar reminiscences leave no doubt that he admired Jackson much more than Longstreet, almost wistfully recalled: "Every battle our regiment had fought [up to that time] was under Jackson. This was his first battle after we left his corps and his last one." While camped at White Hall, which was then owned by a planter named Albert Hill, Captain Oates of Company G was promoted to Colonel and given command of the entire Fifteenth Alabama Infantry Regiment, to succeed Colonel Canty, who was himself promoted to the rank of brigadier-general. It was also at White Hall, recalled Oates, where "the men of the Fifteenth first considered their right to vote, which the legislature had attempted to secure to them by statute." Although the men "held a convention" and nominated their new colonel to run for a place in the Confederate Congress, an honor he declined, the law was never amended to allow them to vote outside their home counties, which they obviously could not do while serving in the army. "After remaining several days at Whitehall," Oates remembered, "we marched to the Rapidan River." From there, he remembered, the Fifteenth Alabama was sent "first to Morton's Ford, where we remained about a day or two," then "ordered to move up the river and encamp at a point convenient to Porter's Ford and to keep a strong picket at the ford, with instructions to resist to the utmost any efforts of the Federals to cross the river at that point." It was here on the south side of the river, recalled Oates, that he and his men "were most pleasantly situated…in a beautiful grove a half mile in rear of the ford," which was actually called Raccoon Ford. Writing about it nearly a half century after the war, it appears that Oates mistakenly recollected that the river crossing at that place was named for the Col. John A. Porter family, one of "the best in Virginia" who lived nearby in a sumptuous residence. Porter's twenty-three year old daughter, Miss Fannie, "was a charming young lady" who entertained Oates "with her sweetest songs" during his "daily visits to the house," where he also "enjoyed…many good dinners." Colonel Oates was apparently so charmed by the place as well as by Miss Fannie Porter that he "would have been willing to have remained at that camp to the close of the war." Many years later he wistfully wondered, "what ever became of Miss Fannie?" William Jordan likewise remembered the Fifteenth Alabama's camp near Raccoon Ford with fondness. "The finest clover pasture I ever saw was there," he recalled, "owned by Colonel Porter and as fine milch cows," which some "of the soldiers would milk…in their canteens." One day, Jordan remembered, he "got a pass to go foraging and got a good dinner at a Mrs. Stringfellow's about one mile from the ford."

Although "the whole regiment liked that camp," recalled Oates, their enjoyment of it was fleeting. In early June, they "were marched down in the fork of the Rappahannock and Rapidan and made a demonstration as though intending to cross the former and attack Hooker." Oates recollected that he "was ordered to take the regiment after nightfall, to a position at a ford and at daylight next morning to charge across the Rappahannock and kill, capture or drive away a regiment which occupied an old canal on the opposite bank, for the purpose of effecting a crossing." With a "battery of General Alexander's artillery…in position on a hill in my rear," Oates made ready but "just before day" orders came for the regiment to withdraw, for reasons that the Colonel never learned. Many years later he remained convinced that if "General Lee [had] persisted in this movement, there would not have occurred the battle of Gettysburg." Following the regiment's withdrawal from their position at the confluence of the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers, they "retraced" their "steps and went into camp between Stevensburg and Culpeper Court House in neighboring Culpeper County. The Battle of Gettysburg

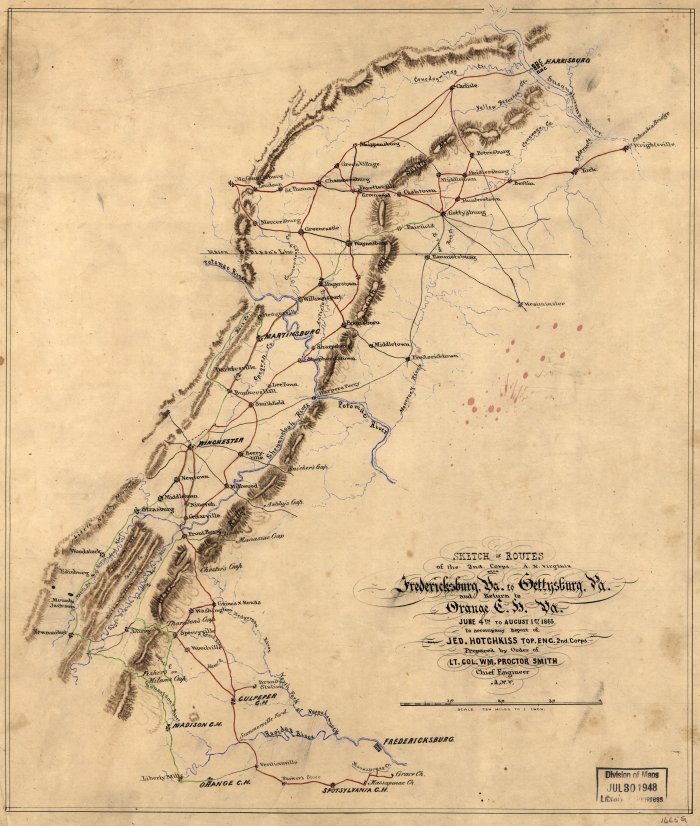

Longstreet's Corps, which included the Fifteenth Alabama Infantry, was still camped in Culpeper County when in mid-June the order came to march north. Their commander, Gen. Robert E. Lee, in a bold but desperate move, had decided to take the war to Pennsylvania, "to let the people of that state fell the scourge of war and imperil the Capital at Washington." There was another reason: At this time, Vicksburg, Mississippi was under siege by federal troops led by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Consequently, recalled Colonel Oates, "the Confederacy was in danger of bisection." Lee's purpose was also to "cause such a withdrawal of troops from Grant's army to send against his and protect Washington as to raise the siege and relieve Vicksburg." It was a grand plan that was ultimately doomed to failure. On June 10, Lee's invasion force, numbering some 75,000 men, began their long march north. To "shield his movement from [General] Hooker, who was then in command of the Union Army, and to keep him in ignorance, as far as practicable," Lee marched his men "through the Shenandoah Valley in rear of the Blue Ridge Mountains." General Ewell and the Second Corps took the advance while the Third Corps, led by Gen. A. P. Hill, and the First Corps under Longstreet, brought up the rear. Not surprisingly, Lee's troops made up a long column, with a supply train of wagons that stretched for seventeen miles! On June 19, recalled Oates, Longstreet's First Corps "held the Blue Ridge at Ashby's and Snicker's Gaps, while Hill, with the Third Corps was passing down the valley in his rear."

On June 20 Isaac Tate and his fellow soldiers waded across the Shenandoah River and on the 23rd, they crossed the Potomac at Williamsport, Maryland. As they moved North toward their rendezvous with destiny, Isaac Tate and his comrades may have either witnessed or been part of an amusing episode that occurred as General Longstreet observed his men wading across the Potomac River at Williamsport. So as not to get their trousers wet, some of the men removed them while wading across the shallow river, and held them bunched up over their heads but as they were making their way to the opposite shore a carriage-full of young Maryland women happened to pass by. The soldiers, of course, were embarrassed to be caught literally with their pants down (or off in this case). This humorous scene was almost certainly forgotten, however, as the Confederates made their way into Pennsylvania and an encounter with the Union's Army of the Potomac became more and more of a possibility. "After crossing the [Potomac] river and marching through Hagerstown [Maryland]," recalled Oates, "Hood had issued to his division several barrels of captured whisky, and the consequence was that there were quite a number of drunken officers and men. This…was the case in the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment." That afternoon, he recollected further, "We marched into Pennsylvania…and went into camp before night near Greencastle." While riding with his adjutant in the countryside that same day, Oates was upset to find "some of the soldiers committing depredations upon the Dutch [actually, German] farmers, which I promptly rebuked, and ordered the men to camps wherever we found them." Thinking perhaps that history might misjudge, Oates added that these so-called "depredations" were nothing more serious than the "taking of something to eat and burning fence rails for fuel." That evening, while Private Isaac Tate and his fellow enlisted men were cooking their dinners over campfires, Colonel Oates "took supper…with some very loyal people to the Union," whose home he had guarded to protect the inhabitants "and their property from trespass and spoliation." The following day, when the Confederates resumed their northward march, they passed through Chambersburg. After closing all their houses, curious townspeople "stood in crowds on the sidewalks and at the upper-story windows to see the 'rebels pass," recalled Oates. Obviously not wanting to incur any ill will, "Guards were stationed to prevent depredations [upon civilian property] by our troops." That night, the Confederates "encamped beyond the town." The next day, Wednesday, July 1, 1863, the greatest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere began. It started when "one of A. P. Hill's divisions learned of a reported supply of shoes at Gettysburg, a prosperous town served by a dozen roads that converged from every point on the compass. Since Lee intended to reunite his army near Gettysburg, Hill authorized this division to go there on July 1 to 'get those shoes.'" Unfortunately for the shoeless Confederate soldiers, "they found something more than the pickets and militia they had expected. Two brigades of Union cavalry had arrived in town the previous day." When "each side sent for help," the Confederates arrived first "and by afternoon had driven the Federals south of town, where they rallied into defensive position on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill." When the sun rose the following morning, after more divisions arrived throughout the night, some "65,000 Confederates faced 85,000 Federal troops" across the farm fields of rural Pennsylvania. The Fifteenth Alabama Infantry Regiment was still in camp outside Chambersburg when the fighting began at Gettysburg on Wednesday. Here is how Colonel Oates remembered the events of that day:

(Note: The "Thad Stevens" referred to above was Senator Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, an ardent abolitionist and anti-secessionist. No doubt the Confederates who fired his property took great delight in doing so.) As he and his regiment came upon the battlefield from the west, Oates observed General Lee and General Longstreet "together on an eminence in our front-on Seminary Ridge." They "appeared to be inspecting with field glasses the position of the Federals." After resting for only "a few minutes," both Hood's Division (of which the Fifteenth Alabama was a part) and McLaws' Division were "moved in line by the right flank around to the south of the Federal position " Oates later recalled "There was a good deal of delay on the march, which was quite circuitous, for the purpose of covering the movement from the enemy." At length, he added, Hood's men "marched across the rear of McLaws [division] and went into line on the crest of the little ridge across the Emmitsburg Road, with Benning's brigade in rear of his center, constituting a second line-his battalion of artillery, sixteen pieces, in position on his left." Afterwards, McLaws' Division "formed his division of four brigades in two lines of battle on Hood's left, with sixteen pieces of artillery in position on McLaw's left." "This line," remembered Colonel Oates, "crossed the Emmitsburg Road and was partially parallel with it." The extreme right of the line, where Law's brigade, which included the Colonel and his men, was situated, "was considerably in advance and north of that road, and its right directly opposite to the center of the Great Round Top Mountain." "My regiment," recollected Oates, "the Fifteenth Alabama, in the center, the Forty-fourth and Forty-eighth Alabama regiments to my right and the Forty-seventh and Fourth Alabama regiments to my left" were "thus formed" when at "about 3:30 o'clock P. M., both battalions of artillery opened fire." As Union artillery opened up a return fire from near the small hill called Little Round Top, Oates and his men "advanced in quick time under the fire of our guns, through an open field about three or four hundred yards and then down a gentle slope for a quarter of a mile, through the open valley of Plum Run, a small muddy, meandering stream running through it near the base of the mountains." Unfortunately, Oates later remembered, the advance was "not skillfully made in all respects" and owing to the failure of brigade commanders to communicate to regimental commanders "as to what was intended to be done" until after the advance was well underway, two companies of the 48th Alabama and three of the 47th, which might have been made a difference to the outcome of the fierce fighting that Oates and his men later encountered, advanced further than necessary and consequently, were not present when they were needed most. As Law's brigade went forward through the shallow valley of Plum Run, Oates and his men saw that they were "a little in advance" of the other regiments, owing to the Fourth Alabama being ordered to attack Federal troops in the boulder-strewn area called "Devil's Den" and the Forty-eighth being "continued as a reserve or second line." This put the Fifteenth Alabama "on the extreme right of Longstreet's column of attack." With "Benning's, the Texas, and Anderson's brigades moved in echelon into the action," it had the effect of making Hood's Division "spread out like the outer edge of a half-open fan, and as the right drove the enemy from the base of the mountain [Big Round Top], each brigade in succession would strike the enemy's line on the flank or quartering, so that as we drove them our line would shorten and hence strengthen." As the Fifteenth Alabama was advancing, General Law, who had succeeded to command of the division after General Hood was severely wounded, rode up to Colonel Oates and ordered him to "hug the base of Great Round Top and go up the valley between the two mountains" until they found "the left of the Union line" and then "do all the damage" they could. Oates later remembered that Law also told him "that Lieutenant-Colonel Bulger would be instructed to keep the Forty-seventh closed to my regiment and if separated from the brigade he would act under my orders." "Just after Plum Run," recalled Oates, "we received the first fire from the enemy's infantry. It was Stoughton's Second Regiment United States sharp-shooters, posted behind a fence at or near the southern foot of Great Round Top." At this point, remembered the Colonel:

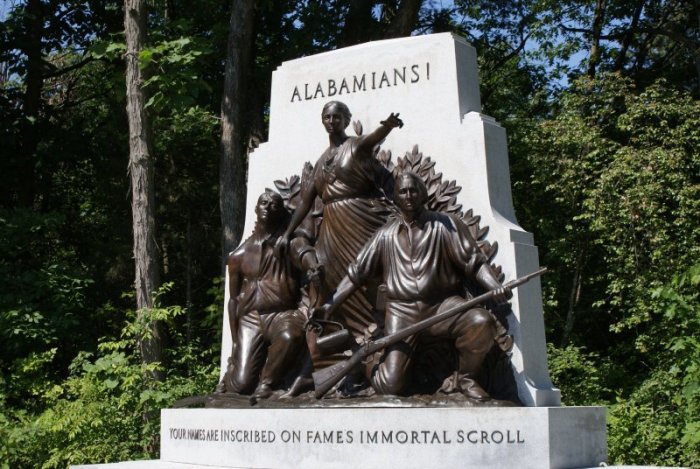

"As we advanced up the mountain," Oates recalled, the Federal troops "ceased firing about half way up, divided and a battalion went around the mountain on each side." To meet them, the colonel "deployed Company A," the company to which Isaac Tate and his brother James were attached, "and moved it by the left flank to protect my right." Meanwhile, Oates and the rest of the regiment continued their "rugged ascent until we reached the top." Here is how one writer described their arrival there: At length Oates' men arrived; sobbing for breath, on the summit of Big Round Top, 305 feet above the plain, the highest point for miles around. Oates let his men rest for a few minutes while he surveyed the scene to the north. Through the foliage he could see all the way to Cemetery and Culp's Hills. There, and down the crest of Cemetery Ridge, Federal troops were digging in; to his immediate front, on Little Round Top more than 100 feet below him, a few Federal signalmen were wig-wagging their semaphore flags. Then, and for the rest of his life, William Oates was convinced at that moment, he held the key to Gettysburg. If a few artillery pieces could somehow be man-handled up Big Round Top and a field of fire cleared by ax men, the Confederates would possess what Oates called " a Gibraltar that I could hold against ten times the number of men that I had." And from that height, the guns could blast the enemy line from one end to the other." Many years later, reflecting on his regiment's arduous climb up Big Round Top (or "Great Round Top" as he called it), carrying "accoutrements, rifles, and knapsacks" while being fired down upon, Oates was astonished but also very proud that his exhausted, thirsty men had been able to accomplish it. "Greater heroes," he wrote, "never shouldered muskets than those Alabamians." He recalled too that earlier, when he and his men were first forming for battle, "a detail was made of two men from each of the eleven companies of my regiment to take all the canteens to a well about one hundred yards in our rear and fill them with cool water before we went into the fight." Unfortunately, he also remembered, "Before this detail could fill the canteens the advance was ordered" and although "It would have been infinitely better to have waited five minutes for those twenty-two men and the canteens of water…generals never ask a colonel if his regiment is ready to move." Consequently, not only did his regiment go into battle without having any fresh water to drink following a forced twenty-five mile march but also the twenty-two men who had been detailed got lost in the woods, "walked right into the Yankee lines and were captured, canteens and all." As Oates' fatigued troops were catching their breath and he surveyed the scene while imagining a Confederate victory, a courier arrived with orders from General Law ordering them to abandon Big Round Top and seize adjacent Little Round Top. Reluctantly obeying these orders, Colonel Oates led the Fifteenth Alabama down Big Round Top into the "saddle" between the two hills. Along the way the Fourth Alabama and the Fourth and 5th Texas regiments joined them. In all likelihood the Confederates expected little or no opposition. Colonel Oates had seen only a few Federal signalmen during the brief ten-minute respite the Fifteenth had earlier enjoyed. No enemy troops were in sight as the men began their ascent of Little Round Top. Then, suddenly with no warning, from behind a collection of large rocks only fifty yards in front of them came an onslaught of what Oates later recalled as "the most destructive fire I ever saw." A soldier in the 5th Texas was more descriptive when he wrote that, "The balls (were) whizzing so thick it (looked) like a man could hold out a hat and catch it full." The Federal troops had only been there a short ten minutes when the Alabama and Texas outfits arrived. Federal General Gouverneur Warren, who had been alerted to the presence of Confederates in the vicinity of Little Round Top by the same signalmen Colonel Oates observed from atop Big Round Top, was the one who had ordered them to go there quickly. The fighting that followed was some of the fiercest that occurred at the Battle of Gettysburg. Facing the 20th Maine, a regiment led by Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, the Fifteenth Alabama staggered back from the initial volley that had caught them unawares. But they quickly reformed and charged again up the hill against an onslaught of bullets so deadly that according to Colonel Oates, "my line wavered like a man trying to walk against a strong wind." When the Alabama troops tried to get around the Federals' left flank, the 20th Maine fell into a V-shaped formation to counter the Confederate movement. A private of the Maine regiment described the battle as "a terrible medley of cries, shouts, cheers, groans, prayers, curses, bursting shells, whizzing rifle bullets, and clanging steel. The air seemed to be alive with lead. The lines at times were so near each other that the hostile gun barrels almost touched." During the fight, Lt. John Oates, the younger brother of Colonel Oates, was shot and mortally wounded. William Jordan recalled that "Captain Brainard of Company G was also killed and Lieut. Coles B. Feagin lost a leg." Shouting, "Forward my men, to the ledge!" the Colonel then fired his revolver and led a surge of Alabamians toward the Federal line, a mere thirty yards distant. Captain Howard Prince of the 20th Maine later wrote, "Again and again, this mad rush repeated, each time to be beaten off by the ever-thinning line that desperately clung to its ledge of rock." The 20th Maine's commanding officer, Colonel Chamberlain recalled how "the edge of the conflict swayed to and fro, with wild whirlpools and eddies. At times I saw around me more of the enemy than of my own men; gaps opening, swallowing, closing again with sharp convulsive energy. All around, a strange, mingled roar." Finally, as the Confederates rallied for yet another charge, Colonel Chamberlain had his men fix bayonets and then shouted for them to charge the Confederate troops. The noise of battle was so loud however that hardly anyone heard him and no one in the 20th Maine moved from their positions until a lieutenant jumped out in front of the line, yelled to his men to follow, and charged alone! For a moment, only a few soldiers followed him and then suddenly the entire 20th Maine, or what was left of it, erupted into a charging line down Little Round Top, led by Colonel Chamberlain with his upraised sword.

At the same time the men of the 20th Maine were charging toward the Alabamians and Texans from the front, Stoughton's Federal sharpshooters came up unexpectedly from behind and also fired on them. It was horrible. Colonel Oates later wrote, "While one man was shot in the face, his right-hand or left-hand comrade was shot in the side or back. Some were struck simultaneously with two or three balls from different directions." At first, Oates was determined to "sell out as dearly as possible" but then changed his mind. Quickly, the order was passed for everyone to get out as best they could and as the Colonel himself described it, when the signal was given, the Confederates "ran like a herd of wild cattle." Private Isaac H. Tate and his brother James were fortunate to be absent from their regiment's bloody confrontation with the 20th Maine. Earlier, when they and their fellow Alabamians were descending Big Round Top, "in rear of Vincent's spur," and making their way into the "saddle" where Chamberlain's men were waiting to ambush them, Colonel Oates had spotted some "Federal wagon-trains" as well as "an extensive park of Federal ordnance wagons" only "three hundred yards distant" and ordered Captain Shaaf "to deploy his company, A," to "surround and capture the ordnance wagons, [and] have them driven in under a spur of the mountain, and detached his company for this purpose." This does not mean however, that these men completely missed the action. When Capt. De B. Waddell was retreating from the battle with the Maine men, recalled Oates, he encountered "Company A coming out of the woods to the east of the position from which we had just retreated." This was the company whose captain I [Oates] had ordered, as we advanced down the north side of Great Round Top, to deploy his company in open order to surround and capture the train of [Union] ordnance wagons. Captain Shaaf claimed that there were Union troops in the woods east of the wagons and he feared capture of his company if he attempted to capture the wagons, and desisted in consequence. He should then have rejoined the regiment but did not. The troops in the woods were Stoughton's sharp-shooters, and perhaps Morrell's company of the Twentieth Maine. Waddell caused the company to take a stand a short distance up the mountain-side, where by their fire they checked and turned back the Maine men who were pursuing my regiment. "The absence of Company A from the assault on Little Round Top, the capture of the water detail, and the number overcome by heat, who had fallen out on scaling the rugged mountain" Oates later recalled, had "reduced my regiment of less than four hundred officers and men who made that assault." Oates himself had been "so overcome by heat and exertion" that he "fainted and fell, and would have been captured but for two stalwart, powerful men of the regiment, who carried me to the top of the mountain, where Dr. Reeves, the assistant surgeon, poured water on my head from a canteen until it revived me." Still feeling fatigued, Oates "turned over command of the regiment to Captain Hill temporarily, with directions to retire to the open field at the foot of the mountain on the line with our advance." This was at dusk, Oates recalled, by which time "the fighting along our line had pretty well ceased." That night, while Private Isaac Tate and his fellow Alabamians "bivouacked for the night" in the little valley below Big Round Top, Federal troops moved in to occupy it. "After all had gotten up," remembered Colonel Oates, he ordered "the roll of the companies to be called." In doing so, Oates discovered that his regiment, which had previously been the "strongest and finest regiment in Hood's division," had been whittled down to about half its original strength of five hundred officers and men.That night, Oates also recollected, a few of his men "voluntarily went back across the mountain, and in the darkness penetrated the Federal lines, for the purpose of removing some of our wounded." Unfortunately, he added, they were discovered by Union skirmishers and were consequently unsuccessful in their self-assigned mission, "but succeeded in getting back to the regiment." Reflecting on the events of Thursday, July 2, 1863, Colonel Oates had nothing but praise for the men he commanded:

Although Confederate General George Pickett's disastrous charge across the open field between the Confederate line on Seminary Ridge and the Union line on Cemetery Ridge has gone down in history as the main event of the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg (Friday, July 3, 1863), it was not the only action occurring. More than twenty years later, in an article written for the Century magazine, former Confederate General Evander M. Law, who commanded the brigade that included the Fifteenth Alabama Infantry, recalled that "little or nothing has been written on the Confederate side" in regard to "the operations of Lee's extreme right wing, extending to the foot of Round Top," which "was held by Hood's division of Longstreet's Corps." In Law's opinion, "This…was really the key to the whole position at Gettysburg" because it was there that "some of the most stubborn fighting of that desperate battle was done, and here a determined effort of the Federal cavalry to reach the right rear of the Confederate Army on the 3rd of July was frustrated." Many years later, William C. Oates recalled that day. "On the morning of the 3rd of July," he later recollected, "Law's brigade still constituted the right of the Confederate line and lay along the second foot, up near the abrupt rise on the south side of Big Round Top, my regiment [the Fifteenth Alabama] on the right." Some "old rocks piled up as breastworks," which were still there decades later when the Colonel revisited the battlefield, marked "the place where the brigade lay." Union cavalry commanded by Gen. Hugh Fitzpatrick "were in the woods just on our right flank, which necessitated the extension of a line of pickets for some distance southward and nearly at right angles to our line." Union sharpshooters positioned on Big Round Top "made it a very precarious business for our men to go down to our rear from water." By chance, a private of the Fourth Alabama, "on picket and acting as a scout on our southern line, overheard in the woods some loud talk between Generals Kilpatrick and Farnsworth and reported it to General Law at once, by which he was enabled to prepare for what was coming-namely a cavalry charge "through our skirmish line" for the purpose of capturing "a six-gun North Carolina battery in our rear." As Farnsworth and his men struggled to cut their way through Texas, Alabama, and Georgia troops who stubbornly resisted the Federal charge, as well as dodge artillery fire from the very battery the Union men were attempting to capture, Oates and the Fifteenth Alabama, which had been ordered to move "from the right…with all possible expedition to the relief of the battery" ran "through an open space and crossed Plum Run," then "rose the ascent in a copse of woods" where they encountered "some eight or ten cavalrymen" who "came in between us and the battery." At that moment, one of the Confederate cannons sent "a double charge of canister-shot at the cavalry, which, missing them, came over our heads and through the ranks, making a noise resembling that of the wings of a covey of young partridges, but did us no damage." In his memoirs, Colonel Oates described what happened next:

Whether or not Private Isaac Tate was one of the Alabamians who fired on Farnsworth is unknown but it's possible he witnessed this event. Afterwards, Oates allowed his men "to rest where they were" and while he was sitting on the field, resting himself, one of his men came up to him "and said, 'Colonel, don't you want that Yankee major's shoulder straps?' holding them up before me." he man was mistaken, Oates later recalled. "He supposed that the dead man's rank was that of major because he had but one star on each shoulder strap-a single star on the coat collar indicating that rank among the Confederates." After taking the straps and realizing that they indicated the dead officer was a Union general, Oates got to his feet and "went to the body," which lay "not more than fifty steps" away." A number of curious enlisted men were also "coming up to it in little squads and looking at the dead man in silent amazement on account of Lieutenant Adrian's statement." In Farnsworth's coat pockets, Oates found some private letters, which confirmed his identity and which the Colonel afterward destroyed "to prevent their falling into the hands of irresponsible parties." Later that afternoon, Oates recalled, the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment was ordered "to take up an advanced position in the woods facing east and at right angles to our line at the base of Round Top, but separated from it by a half mile or more southward." After the Alabamians had obeyed the order, which put them within one hundred yards of "a strong line of dismounted [Federal] cavalrymen," a pouring rain commenced. By nightfall, they were still there, their "surroundings" presenting "the most weird and lonely appearance," with the bodies of dead men lying "scattered through the drear and somber woods" while "fast-scudding clouds overhead shut out all save just enough light, at short intervals, to get a glimpse of the solemn scenes around us." As the hours passed with no new orders, Oates began to think "there was something wrong." When he rode into the woods a little way to investigate he "heard a gun or pistol cap explode a short distance from me." Sending a scout to investigate, the Colonel learned that Federal troops were still "within a hundred yards." It was after nightfall, very dark, with Yankees near to us in front and rear. No orders came and I was satisfied that none would come, except from our enemies, and that would be to surrender whenever they found us isolated from the main body of our troops. I resolved to act upon my own judgement, abandon the post without orders, and get out of there. I knew the penalty for disobedience of orders and abandoning my post in the presence of the enemy-it was infamous death if I made a mistake. I was sure of my position, and I took the responsibility, grave as it was. I therefore drew in the videttes from my left and front, faced the regiment to the right, and ordered the men silently to march after me. No man spoke above a whisper or made any noise. After performing a considerable circuit, the rain pouring down at intervals, we got into the open field and marched westward until we heard troops in our front building breastworks. I did not know which side, but ventured, and to our great relief found our place in the line of Longstreet's corps, and thus escaped from a most perilous situation. We were fortunate too, in reaching that line at our brigade.

Oates later learned that when General Lee had ordered Longstreet to "retire on a line with Hill's corps and fortify his position" in anticipation of a Federal attack, orders had likewise been sent to order the Fifteenth Alabama to withdraw, "but the courier was captured and did not reach me." Consequently, he later recalled: "The Union army had advanced, and I was nearly surrounded, and happened to take the only safe retreat. Had I obeyed orders I and all of those with me would have finished our service as prisoners of war, a thing I always dreaded more than the bullets of the enemy." On July 4, Oates recalled, the Confederates awaited "an attack of Federals, but they came not." William Jordan remembered it as "the coldest fourth of July I ever felt." He also recollected that "some houses between us and enemy, which obstructed our view" were "set on fire and burned" :It was pleasant," he added, "to get near the burning houses to warm." The following day, July 5, 1863, "Lee began his retreat toward the Potomac." At the Battle of Gettysburg the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment began with a complement of 644 men. By battle's end on July 4 they had suffered 72 killed, 190 wounded and 81 missing. Considering the fierceness of the fighting in which the regiment took part, I find it incredible that my great-grandfather survived. When the Confederates began their back to Virginia on July 5, Colonel Oates "rode to our field hospital and saw as many of our wounded as I could before leaving." Remarkably, "Hood's division was not molested by the enemy on its retreat," but it continued to rain so hard that after three hours, the men were allowed to stop and build fires and dry "by them for two hours" before recommencing their southward march. Unfortunately, recalled Oates, when they reached the Potomac River crossing at Williamsport, Maryland, "we found the Federal cavalry, and a rise in the river had broken and carried away or destroyed a part of the pontoons, and the river was not fordable." Expecting an attack by General Meade, who had succeeded to the command of the Union army just prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, Lee's men prepared for a fight that never came (much to the consternation of President Abraham Lincoln, who never forgave Meade for failing to destroy Lee's forces while he had them defeated and on the run). Finally, after several days had gone by, "Lee transferred his army to the Virginia shore," some fording at Williamsport while others "crossed over a pontoon bridge near Falling Waters." In the process, Oates remembered, "General Pettigrew was killed, and by mismanagement of subordinates and a ruse of the Yankee cavalry, Lee lost 2,000 prisoners." "Thus ended the Pennsylvania campaign, the second invasion of Union territory." William Jordan remembered seeing General Lee at Falling Water, where the Fifteenth Alabama crossed the Potomac, "on his horse, on the west bank of the river, having artillery placed in position in the event it was necessary to protect his rear guard and stragglers; he seemed to be intent and eager for the last man to get over, without molestation." Like most Southern soldiers, it seems, Jordan venerated Lee as a "great, grand and extraordinary man." In Jordan's opinion, Lee "was superior to any man that has been tested in America" and "had no equal as a commander, north or south." Upon reaching Virginia, the Fifteenth Alabama "marched leisurely through the Valley and across the Shenandoah," recalled Colonel Oates, "our corps of the army passing through the Blue Ridge at Front Royal and Miles' Gap." William Jordan remembered that Company A, the unit to which Isaac Tate and his brother James were attached, generally took the lead. When Federal troops tried "to impede our march" they were simply "brushed aside." At about noon on July 23, when "the men had just eaten the last rations they had" and the regiment reached the spot where the Warrenton Pike crossed the road they were following toward Culpeper Court House, Oates received orders for he and his Alabamians "to turn square off toward Warrenton for one or two miles until I found a good defensive position, and there to remain to protect the flank of the marching column until relieved." Many years later, he described what happened next in his memoirs:

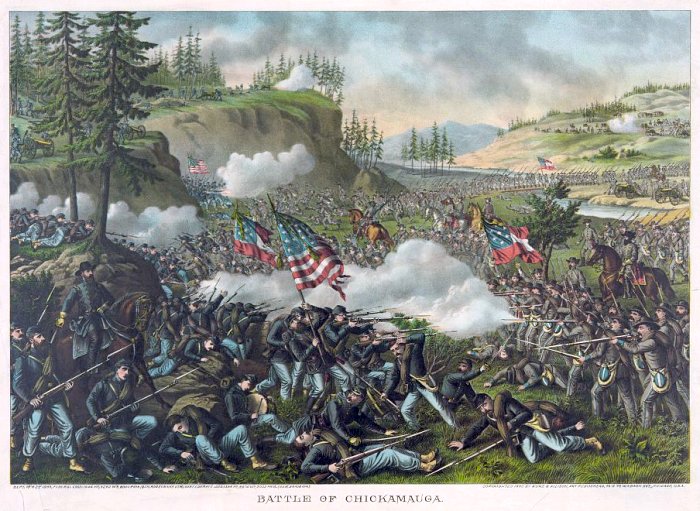

The following morning, Oates allowed his men to breakfast on "a large patch of ripe blackberries," owing to the fact that their "rations were exhausted the day before." Then, at 9 a.m., the men of the Fifteenth Alabama resumed their march. They hadn't got very far however, when they were compelled to fight again, this time with Union cavalrymen led by General Kilpatrick, which were "discovered in battle array up on the side and top of the mountain, with a battery in position that commanded the road." Holding most of his men "in close supporting distance," Oates sent four companies which were successful in driving the Federal troops "to the top." In this effort, one officer was killed and three enlisted men wounded. At this point, Oates and his men were joined by Gen. A. P. Hill's troops, who assisted the Alabama men by opening "an enfilading fire" on the Union battery. Then, just as Oates was about to attack with his "whole regiment," General Benning, "who had turned back when he heard the firing, marched his brigade through the woods right up to the rear of Kilpatrick's men, fired upon them, and killed and wounded about one hundred, when the command fled to a more healthful locality." Afterwards, the Fifteenth Alabama resumed its march once more and upon reaching Culpeper Court House, where they "received rations," Oates' men "ate as only hungry soldiers could." When they were finished, they dug a grave and buried the lieutenant who had been killed (E. P. Head), "was buried with full military honors." After camping at Culpeper for "several days," the Fifteenth Alabama was "moved over on the Rappahannock," where they stayed until early September, "drilling, moving and changing camps occasionally for the health and comfort of the men." The Battle of Chickamauga

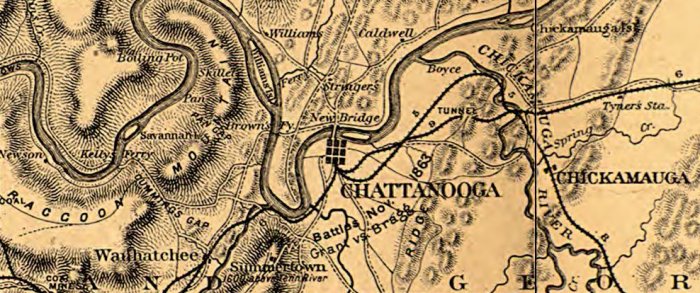

On September 9, 1863, Longstreet's Corps, to which the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment was then still attached, "was ordered to take two divisions-Hood's and McLaws's-and reinforce Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee, which was then in the vicinity of Ringgold, Georgia, to which place it had been compelled to retire before the advance of the victorious army of [Union General] Rosecrans." Traveling more than five hundred miles by train, the troops experienced "no occurrence of sufficient moment" except that when they stopped in some of the towns along the way, they were often treated to "abundant and excellent lunches," which had been prepared by "patriotic people, especially the good ladies." Not surprisingly, this food was "greatly enjoyed" by the men, who often did not know when they would get a chance to eat again. William Jordan, who remembered that the "cars were jammed and packed inside and out, " chose to ride "the entire way on the top of a box car." No doubt he was not alone in what must have been a very windy and oftentimes smoky ride. Upon arrival in Atlanta, which was only a hundred miles northeast of Private Tate's home in Opelika, Alabama, the troops were "delayed about one day on account of crowded conditions of railroads and insufficiency of rolling stock." Finally, the Fifteenth was "transferred down to Ringgold," where they "arrived on the 16th and encamped for the night, but without baggage and camp equipage, which had been left behind." William Jordan recalled that after "passing through the tunnel," they arrived "about 12 o'clock at night" and "stacked arms in an old field." The following day, after the regiment "hastened" to Ringgold in response to an alarm-some Union cavalry scouts had been seen but "disappeared," Oates and his men "marched westward several miles, and passed over ground where Hood," who had arrived earlier, "had fought and driven the Union cavalry." From time-to-time, the corpse of some unfortunate soldier was seen. "We marched and we marched," Oates later remembered, "along the dustiest roads I ever saw, and camped; got up the next morning and marched back again." Unfortunately, he also recollected: "This exhausted the rations, as we marched on the 17th [of September] with only two days' supplies in the haversacks." On September 19, the day the Battle of Chickamauga began, the Fifteenth Alabama "crossed the creek of that name in the woods about 10 o'clock A.M. and went into line without breakfast." They were ordered "to take a position in the front line on the right of the Texas brigade and to act with it." After a while, the Alabamians were "ordered back to the left of Law's brigade when it was placed in the front line." Finally, at 4 p.m., while a "brisk artillery duel was gotten up on our part of the field," the line of Alabama and Texas men "advanced, encountered the enemy, and drove them very easily." When Colonel Perry of the 4Fourth Alabama, who "ranked" Oates somehow became "disconnected" from the fighting, Oates "assumed command of the four regiments of the brigade and soon after crossing the Lafayette Road halted" when no Union troops could be seen. At that moment, the brigade on the left, commanded by Bushrod Johnson, "was fired on from the front and at once retreated across the road and up the hillside with the Yankees in close pursuit." Seeing that "they had passed my line," recalled Oates, "I gave the command 'about face,' which attracted their attention and they fired on my left," killing one officer and one enlisted man. Ordering "the brigade to fall back to the road," Oates called for an immediate halt after "a panic" set in and ordered "the officers to draw their pistols and shoot any man who crossed…against orders." Finally, Oates "moved [the troops] back east of the road, swung back my left a short distance and threw forward eight companies of skirmishers, two from each regiment, and advanced them against the flanks of the brigade which was pursuing Johnson and soon drove it back across the road and into the woods beyond." At nightfall, Oates "sent to division headquarters an order for rations." At that point, his men had not eaten for an entire day. "If anything will make a man hungry," commented the Colonel in his memoirs, "it is hard fighting." Finally, at 1 A.M., the rations arrived "and the men awoke at that hour and ate most ravenously." When the battle recommenced on September 20, recalled Oates, General [Leonidas] Polk, who commanded the right wing, planned "to attack…at daylight and drive Rosecrans's left wing, double it back on his center and cut him off from retreat to Chattanooga, when Longstreet's wing was to advance and crush him." However, although Chickamauga ended up being a Confederate victory, Polk's plan did not work out as he expected. When the assault began at about 9 a.m. instead of daybreak, "the battle raged with varying success" after "Rosecrans, finding the attack aimed at his left, reenforced [sic] it with troops drawn from his right and center." At 11 a.m., when Longstreet discovered what Rosecrans had done, he "ordered his entire wing forward." "The first line," remembered Oates, was "composed of troops belonging to the Tennessee army." Halting "near the Lafayette Road," they laid down and "kept up an exchange of fire with the Yankees at a distance of two hundred yards while the Union men "kept up a lively fire" from "behind the trunks of trees felled the night previous." When Longstreet's corps, which included the Fifteenth Alabama Infantry, began to advance, they "marched over their friends and routed the Yankees without halting, taking a good many prisoners." Oates recalled that when they "crossed the road it raised a tremendous dust and soon after I could see only a few scattering men of the Union army running away." Suddenly, Oates realized that he and his men were on their own, disconnected with anyone "on the right or left." Pausing to look around, he "saw away to my left and front a fight going on; the Federals in solid phalanx along the pine ridge at the edge of a field, with two pieces of artillery in their midst, were beating the Confederates back down the slope toward the open field." The Colonel later wrote that he had no idea who they were "except that they were Confederates" and that they were clearly in need of reinforcement. Taking it upon himself to act without orders, Oates "resolved to go to their assistance. Here is how he described what happened next:

Oates learned later the commander of the Nineteenth Alabama, Col. Samuel K. McSpadden, filed a battle report in which he wrongly (according to Oates) claimed that the Fifteenth had mistakenly fired on the soldiers of his regiment, thinking they were Union men, until he (McSpadden) ordered his regiment's colors to be waved at them, so as to identify themselves as Confederates. Unfortunately, complained Oates, this erroneous version of events was included not only in McSpadden's report but also the reports of several higher-ups, who did not actually witness what happened, "which did me an absolute injustice." Oates also wrote that he never met the colonel of the Nineteenth Alabama except on the battlefield at Chickamauga, when after the Fifteenth engaged the Federals, McSpadden approached him "and told me who he was and the number of his regiment." "Soon after I spoke with Colonel McSpadden," recalled Oates, "one of my men said 'Colonel, the Yankees are coming up behind us.'" Stepping "out of the smoke," Oates immediately saw that the soldier was mistaken. They were "four regiments" of Gen. Patton Anderson's brigade "coming in splendid style, each carrying the Confederate battle-flag." With all these troops now assembled, Oates ordered a charge. "As we moved," he later recollected, "Deas's brigade, and in fact all of Hindman's division joined in the charge, which swept the Federals form that part of the field." In doing so, the Confederates "captured the battery and a considerable number of prisoners and continued the charge for nearly a mile." Following the charge, Colonel Oates found a horse "richly caparisoned standing near where the Federal lines had broken." His hip still hurting from his injury, which made it difficult for him to walk, Oates started to mount the horse when he saw that it was "shot through the pastern joint of one fore-leg." At that moment he also noticed its rider, Union Gen. William H. Lytle, lying on the ground nearby, mortally wounded. "The dying general lay in the hot sun," Oates recalled later. "I took him by the arms and dragged him two or three steps into the shade and left him and started in pursuit of my regiment." After encountering Gen. Zachariah Deas, who agreed with Oates "that our men were going too far and should be halted," he "found my men lying on the side of a hill, resting, and panting like dogs tired out in the chase." After marching his men "back to the scene of the conflict," the Fifteenth Alabama halted and stacked arms, whereupon Oates told his troops "to help themselves to the hats of the dead men and such of the wounded as would voluntarily give them up." They next "marched out to the soap factory or tannery, hoping to learn the whereabouts of Law's brigade" but upon arrival were ordered by Gen. Bushrod Johnson to "march northward through an extensive old field, where the General's own troops, he said, were "very hard pressed and much in need of reinforcement." In obedience to General Johnson's orders, Oates directed his men to move "through the old field" after first detailing a few of them as "a guard for our captured guns." As the Fifteenth Alabama "moved on across the field" they "passed over ground where there had been hard fighting that morning" and the bodies of dead soldiers could be seen. Finally, the regiment came upon some South Carolina troops but none of Johnson's allegedly "hard pressed" soldiers. There were, however, Union troops "in full view from my position" on a hill or ridge that Oates ordered his men to fortify with logs. After convincing the captain of one company of the Seventh South Carolina regiment to join the Fifteenth Alabama in a charge on the Federal line, "the whole regiment moved," but when they encountered heavy fire, all the South Carolinians except the one captain "ingloriously fled." Many years later, Oates regretted that he had forgotten the name of that "brave man," who he afterward mentioned in his official report of the battle. When Oates ordered his men to return to "the top of the hill," they surprised some Federal troops "were within a few steps on the other side." When the Alabamians opened a "very destructive fire," the Union men "broke and retreated in confusion." One Yankee soldiers, remembered Oates, "threw down his gun and sprang through our lines for protection." Lying behind the logs "we had previously placed," the Colonel wrote, the Alabamians and one South Carolina company "kept up a lively fire on the enemy whenever within range." During the fight, which continued for some time," there was "a constant exchange of shots" but at length "our foes retired slowly, firing until they passed out of range." Unfortunately, recalled Oates, the Federal troops "left in our front several of their dead and wounded, who, when the "woods got on fire" were caught in the conflagration. " Move to compassion by "their agonizing cries," the Colonel "sent out some of our litter-bearers to help save the wounded, but being fired upon by the Union soldiers, I withdrew them." In that particular skirmish, the Fifteenth Alabama's own losses were "four or five" killed and "five or six times as many more…wounded." One of the dead, remembered Oates, was a sixteen-year-old lad named Tom Wright, who was shot in the head only minutes after the Colonel had encouraged him with some kind words and a reassuring slap on the shoulder. Oates later remarked: "There were quite a number of young boys in the regiment, and they made better soldiers than a majority of the grown men. They cared but little about home, were always cheerful, generally healthy, and in battle they never knew when they were whipped." They probably also did not comprehend how unfairly their youth and naiveté were being misused by a government that was very clearly on the wrong side of history. After receiving orders from General Law to withdraw from the action, the Fifteenth Alabama carried their dead from the battlefield and after making camp, they "buried them alongside of each other that night." That same evening, a happy Colonel Oates "visited the camp-fire of every company in the regiment." "We had gone through another great battle," he later wrote, "and the lives of many of us were spared, and we were victorious."

The Battles of Brown's Ferry and Lookout Valley After General Rosecrans conceded defeat at Chickamauga and the Union army retreated back across the Tennessee River to Chattanooga, Bragg belatedly went after him. The Fifteenth Alabama, as part of Law's brigade, "went into position" near Lookout Mountain, a tall precipice overlooking Chattanooga. "We were very scarce of rations," Colonel Oates later remembered, "and for a day or two skirmished pretty lively with our Yankee neighbors over a corn-field to see who should have the most corn to parch." Oates added: "I believe we got the most." Shortly after they first arrived near Lookout Mountain, General Law ordered the Fifteenth Alabama to go "down to a little creek and effect a crossing if practicable, and drive the Federals out of their fortifications," with Law to follow "with the other four regiments and a battery of artillery." Here is how Oates described what happened next:

"At this juncture," wrote Oates, "Law's battery opened on the enemy, and their fire of artillery and small arms in reply was very lively for a while." "The creek," he added, "was of horse-shoe shape, the Federal line being across the toe." Owing to the deep water and "precipitous" banks overgrown with "difficult jungles of vine and undergrowth on each side," the Colonel "decided against the practicability of the movement, and so reported to Law, who approved my decision and withdrew us to our camps." In mid-October the Fifteenth Alabama was ordered to join the Fourth Alabama Regiment and "a section of the Louisiana battery" at the east side of the end of Raccoon Mountain in order to "prevent use by the enemy of the wagon road on the opposite side." To reach the position, Oates and his men had to cross "over Lookout Mountain at night, taking the road by the Craven House." It was a difficult climb.

Later that day Oates was ordered "to take command of the [Lookout] valley, not to interfere with the Fourth Alabama where it was stationed, but to picket the river from that regiment up to Brown's Ferry, and to obtain all the supplies I could legitimately." Obeying at once, Colonel Oates "placed five of the companies on picket along the river" while setting up a camp for the reserves in "a central position" in the valley. Owing to the difficulty of obtaining rations, which "had to be brought to us on pack mules from the other side of the mountain," Oates used his initiative to purchase "a small herd of beef cattle and ninety sheep, all fit and nice, from a Mr. Williams," who had kept a farm on a island in the river until Rosecrans' troops showed up. Unlike a mill owner, who refused to grind corn for them, because he was "a Union man" (in consequence, Oates "impressed" the mill and assigned a soldier with milling experience to run it), Williams "was a true Confederate" who agreed to spy on the Federal troops while visiting the island to ascertain the condition of the livestock he had left behind. Amazingly, he was able to go "all about without encountering any guards" and returned to the Fifteenth Alabama's camp to report that the Federals had only a few pickets stationed "at wide intervals."

Encouraged by this news, that very night Oates personally led forty volunteers under cover of darkness, in a clandestine attempt to try to capture or kill the Federal soldiers who occupied the island but just as their boats drew near, the Union pickets fired on them and the Colonel and his men were forced to give up the attempt. The next day, Oates discovered some clothes near the water's edge and some tracks leading to the river, which led him to suspect that a Confederate deserter had swam across and informed the Federals of the planned attack. One night during the time the Fifteenth Alabama was on picket duty in the Lookout Valley, remembered William Jordan, they were "quite friendly and communicative" with Union soldiers on the other side of the river. Our boys would tease them about hardtacks and they would guy us about corndodgers. I stepped out with a pan of eggs and told them to come over, that we had everything that heart could wish; took my empty [brandy] bottle and handed it around to the boys, and all went through the blank motion of drinking. One Yank said, "I believe that fellow has got spirits." I heard what he said and told him to come over. He said he would the next morning, and exchange papers and swap coffee for tobacco, if his colonel would let him and provided we would not take him prisoner. We told him that we would deal fairly and honorably with him. On October 24, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, whose victory at Vicksburg on July 4, 1863 had given the Federal army and navy control of the Mississippi River, arrived at Chattanooga to take over command from General Rosecrans. On that same day, Grant rode down to reconnoiter the north side of the river, where he wondered that Confederate pickets did not fire on him, and decided that Brown's Ferry "was the place" for an attack. On October 27, an apprehension held by Colonel Oates that he and his men were going to be attacked proved accurate. "Just after dark," he later remembered, a courier arrived with a message telling him "that a heavy force of the enemy, infantry and artillery, were attempting to cross the river south of Raccoon Mountain, near Bridgeport," and that the cavalrymen who had been charged with the defense of that point were "powerless to stop them." The message also warned Oates that he and men were in danger of capture. After sending a message himself to General Longstreet, "with a request to send reenforcements [sic] without delay," Oates tried to sleep but was awoken a short time later by one of his men who had rushed to tell him that the Federals had crossed the river and "had driven Captain Feagin and his company away from Brown's Ferry." In reaction to this news, Oates later wrote, "I had the long roll beaten, and gave orders for the men to leave their knapsacks in camp and their little tent flies standing." After leaving a few ill soldiers behind to guard the camp, the Colonel mounted his horse and set out with the rest of his troops to resist the Federal advance, which he had been told consisted of only seventy-five to a hundred men. Owing to a ridge alongside the river, which concealed the invaders from view, the Alabamians did not see or hear the Federals, who were "at work building breastworks," until they were "within twenty steps of them." It was a close call but they were not seen. As quietly as possible, Oates ordered an about face and then after withdrawing his troops "about a hundred yard," decided on a bold move. "I detailed two companies," he later remembered, ordering their captains "to deploy their men at one pace apart and instruct them to walk right up to the foe, and for every man to place the muzzle of his rifle against the body of a Yankee when he fired." One of these companies was Shaaf's Company A, to which Pvt. Isaac H. Tate was attached. Away they went in the darkness. I could hear nothing more than the enemy's hammering and a stick crack here and there. I waited in breathless silence for them to fire, a much longer time than I thought was necessary; but when they did fire it must have done terrible execution, judging from the confusion of the enemy which followed. I could hear some running through the woods, others crying out, "We surrender, we surrender!" an some of the officers, I suppose, crying, "Halt! halt! Where are you going, you d-d cowards?" My companies got inside their works and drove them, capturing eleven prisoners. But the Federal line to my right fired on us heavily, and to meet that I deployed in like manner Company K and put it into the action. Their fire outflanked me on the right. I put in one company after another, until all six of my reserves were into it, and still I could not cover the enemy's front. Company F-Captain Williams-was the last one I put in. The three left companies got inside the enemy's log defenses which they were constructing and drove them toward the river, capturing the ridge west of the gap; but my other three could not drive the Yankees from their position. Company E (Dale County), Lieutenant Glover, of Company B, commanding, had five men killed-all shot through the head, one right after another. I remember now the name of but one of them-David Snell. I had a bullet pass through my left coat sleeve and my horse was shot. Captain Terrell, of Law's staff, arrived, and I sent him for the Fourth Alabama to withdraw and bring it to my assistance. I next sent a courier down the river to withdraw my other five companies and to bring them as speedily as possible, as I knew then that I was contending with a force greatly superior to my own. The fight continued. I went to the right company, as I could not see the officers, and it was not moving forward. As dawn broke, Oates could "see men twenty or thirty steps distant." After watching a sergeant suffer a severe wound while trying to rally his fellow soldiers, the Colonel himself "rushed in among the men and ordered them forward." When Oates and his troops were "within about thirty steps of the enemy," so close that their heads could be seen "as they fired from behind some logs," the Colonel was shot in "the right hip and thigh, the ball striking the thigh bone one inch below the hip joint." Oates later wrote that it felt "as though a brick had been hurled against me" and cursing as he fell, he stopped short of saying "Goddamn," thinking "it would not seem well for a man to die with an oath in his mouth." Seriously wounded and unable to stand without help, Oates was evacuated by some of his men "to a little house, where many of our wounded had been collected in the yard." There, the Colonel sent word to Captain Shaaf of Company A to tell him "that he was in command, and to use his best judgement but not to lose the artillery, which was then firing from an apple orchard one hundred yards from the little house." Eventually, Oates later recalled, "General Law arrived with the other three regiments of his brigade and the Texas brigade." After stopping to consult with the wounded Colonel, who advised him "that he was too late…to accomplish anything" because "a heavy force had already crossed the river," Law had a look for himself from a nearly eminence overlooking the river. He "soon returned," remembered Oates, "and said I was quite right; that they had laid a pontoon bridge, and had then at least a corps in the valley." Upon realizing the situation was hopeless the Confederates began their withdrawal from the valley. While Oates was being carried by eight enlisted men (four Alabamians and four Texans) back over Lookout Mountain to a field hospital, Law "placed his troops in a position to aid the Fourth Alabama" as well as the five companies of the Fifteenth Alabama "which were on picket" as they "retreated eastward along the Raccoon Mountain." Oates recalled, "Captain Shaaf also succeeded in getting out with the six companies which had been engaged and the artillery." He was proud that although the gunners were prepared to abandon "one piece and one caisson," the soldiers of his regiment "compelled the batterymen to carry them out, and both guns and caissons were thus saved from capture." Unfortunately, he added, "the men who were too badly wounded to travel afoot, our dead, our camp and baggage, with all of the men's blankets and clothing, except what they had on, and a considerable quantity of supplies, were unavoidably left to the enemy." Some critics attributed Grant's success in breaking out of Chattanooga, and the subsequent capture of Lookout Mountain by Federal troops, to the failure of the Fourth and Fifteenth Alabama regiments to hold Lookout Valley. Not unnaturally, Oates was displeased by this analysis, which he felt was unfair. "I knew the importance of holding Lookout Valley," he later wrote, but the defeat at Brown's Ferry "was no fault of mine." If anyone could be faulted, he wrote at length in his memoirs, it was General Longstreet as well as Gen. Micah Jenkins (who had replaced General Hood after he was wounded at Chickamauga), two leaders whose "slothfulness and negligence" was "but little short of criminal." I and my command did all that any equal number of men could have done to hold our position and keep Grant's men out of the valley. What more could 250 men have done against 2,500 than mine did? I was not supported, but sacrificed." Oates also blamed Longstreet for the loss of Knoxville, Tennessee, where the Fifteenth Alabama, which was then being led by Major Lowther while the Colonel recuperated from his wound, was sent in November 1863. At that time, the city was occupied by Union troops under command of Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Oates later charged that Longstreet's "slothfulness" at Lenoir's Station, where the General "had seven thousand of the enemy nearly surrounded," resulted in the Federal troops' escape and their subsequent reinforcement of Burnside's forces at Knoxville. Oates claimed that Longstreet likewise lost "the advantage over his enemy" at Campbell's Station and then unjustly blamed it on General Law, with whom he seemed to have a running feud. When Longstreet reached Knoxville, wrote Oates, "he maneuvered and skirmished before the fortifications several days, until the enemy had made them impregnable." His subsequent sending of troops without scaling letters against the walls of Fort Sanders resulted in "failure and heavy losses." Finally, after remaining "around Knoxville until after Bragg was whipped at Missionary Ridge" and Burnside was reinforced, "Longstreet raised the siege on December 8, 1863, and retreated into Eastern Tennessee." Oates was highly critical:

After Longstreet retreated from Knoxville, he took his two divisions (Hood's and McLaws'), which included the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment, and headed up the Holston River valley until he reached Bean Station. There, together with troops commanded by Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, "these divisions were turned against the Sixteenth Army Corps and Burbridge's division, which had followed them from Knoxville." Following "a lively skirmish," remembered Oates, "the Federals declined a regular engagement and withdrew." Afterward, Longstreet's men "crossed the Holston and reached the railroad at Morristown, where he stopped for a time" before continuing "eastward along the railroad some fifteen miles, where he put his troops in winter quarters." Continue to: Isaac H. Tate in the Civil War, Part Three: 1864

This website copyright © 1996-2011 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |