|

Isaac Henry Tate By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. Isaac H. Tate: The Postwar Years Back Home in Alabama

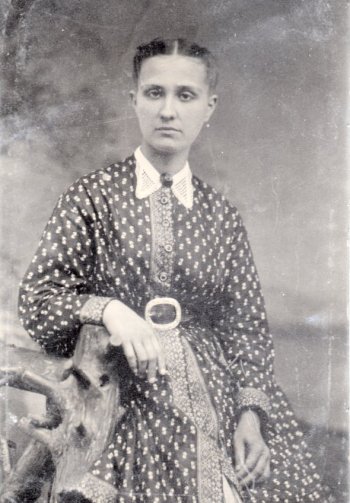

The marriage of Isaac and Sarah Tate provides us with an interesting example of how radically times have changed. In 1865 Alabama, the marriage of a twenty-one year old man to a thirteen-year old girl was apparently not frowned upon. Today, such a union is forbidden by law in nearly every part of the United States, including Alabama, owing not to the fact that they were stepbrother and stepsister but rather to the difference in the couple's ages. We may imagine that the only proviso was that the bride and/or her parents consented. We may be certain however, that there was no immediate need to for a wedding in order to satisfy propriety. Sarah was apparently not pregnant at the time of her marriage to Isaac. Her first child was not born until November 24, 1866-almost exactly one year following the young couple's wedding, which also proves that Isaac's war wound had not unmanned him (as he almost certainly must have worried). In point of fact, during the first twenty-five years of their marriage-from 1866 through 1891-Sarah Tate (see photo below) was almost perpetually pregnant, giving birth to no fewer than fourteen children! Her first child, as noted above, was born when she was only fourteen-years old; the last when she was thirty-nine. Unfortunately, the child-mortality rate during that era was quite high. Of Sarah's fourteen children, only four lived to reach adulthood and of those four, only one was a boy. Tragically, he died at the age of twenty-one, unmarried and leaving behind no male heirs to pass on the family name.

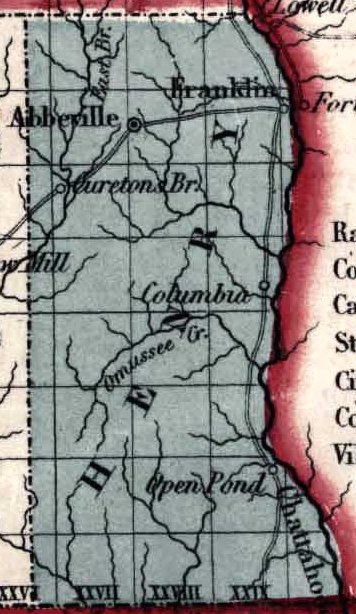

So, despite a large number of births, the Tate household was never overcrowded. Until 1879 there were never more than two living children in the family at any one time. It appears that during the early years of his marriage Isaac H. Tate made his living as a farmer, as did a great many Americans of this era. During the 1860s and 1870s the family lived in Russell County's Wacoochee Valley, in the vicinity of a town called Mechanicsville, which may no longer exist. On December 5, 1866, by an act of the Alabama state legislature, the northern part of Russell County-where the Tate family lived-was formed into a new county named after former Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Portions of neighboring Macon, Chambers, and Tallapoosa counties were also incorporated into this new Lee County, of which Opelika, the largest town, was designated the county seat. It appears that Isaac and Sarah Tate lived at home with their parents for the first seven years of their marriage, either for the sake of convenience, or because they were cash-strapped, or because of a close bond of affection-or in all likelihood, for all three of these reasons. In any case, records on file at the courthouse at Opelika reveal that it was not until December 25, 1873 that the couple finally purchased some property of their own, but even then they did no go far. The land they bought was simply a portion of their parents' own property-152½ acres bounded on one side by the Chattahoochee River, for which they paid $800. About two years later, Isaac slightly increased the size of his farm by paying a Lee County neighbor, K.W. Cone, $85 for an additional 8½ acres of land adjoining his (Tate's) property on the west. The Tate Family in Columbia, Alabama

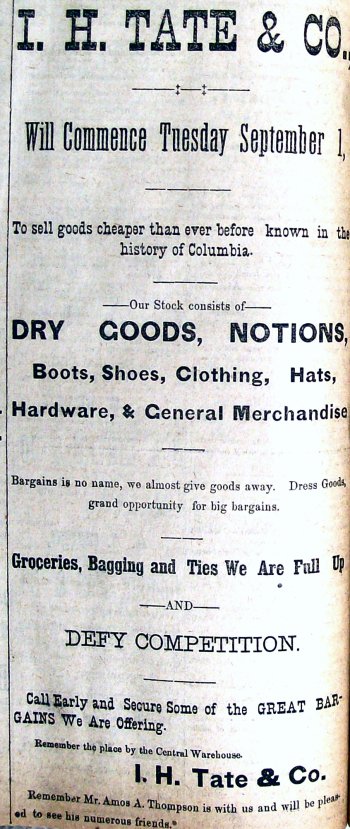

In the absence of any extant personal papers, the public records of Henry County, Alabama are helpful in reconstructing this period in the lives of both Isaac H. Tate and his father Harrison Tate. One of the most important transactions concerning these two men was recorded on April 27, 1881, when together, they purchased a "store house & lot" in Columbia, on Bond Street, adjacent to W.C. Koonce's drugstore, paying $650 to one S. Joseph of Muscogee County, Georgia. Afterward, Isaac opened a general merchandise store on the site, calling it "I.H. Tate and Company." No evidence has been found that his father was a partner or shareholder in the enterprise but it seems likely in view of his involvement in the purchase of the property. Having acquired a place of business, father and son's next step was to purchase a residence. On May 5, 1881, Isaac H. Tate paid John T. Davis and his wife $28 for half of lot no. 8, which lay on the south side of River Street, in the so-called "Davis Addition." Although there seems to be no record of it in the Henry County courthouse, Isaac's father apparently bought the other half of lot no. 8. Four days later, Isaac's stepmother Mary C. Tate paid $150 for the adjacent lot no. 16, located on the southeast corner of River and Davis streets-the latter apparently named for Mr. Davis. Afterward, father and son either built, or hired carpenters to build, houses next door to one another, on their respective pieces of property. Although the Isaac H. Tate house no longer exists, the modest one-story frame house in which Harrison and Mary C. Tate resided was still standing, although slightly modified, as late as June 1997, and may be standing still. After moving to Columbia, Isaac H. Tate sold his farm in Lee County, on December 1, 1881, to one J.H. Howard, for the sum of $800. What prompted this move has been lost to history. Today Columbia, a tiny riverside community with a population of just over 800 residents (according to the 2000 U.S. Census), is situated in Houston County (named for Alabama governor George S. Houston), which was formed in 1903 from the southern half of Henry. We do not know the extent of Isaac's success in his new business during its first few years of operation. Clearly, there were times when sales were in a slump. One advertisement, in the August 1, 1883 edition of the Columbia Enterprise, offered the store's "entire stock of good[s] at cost for the next thirty days," adding: "We mean what we say." Another ad proclaimed:

One of the new company's worst setbacks came in February 1884, when a fire broke out on the premises, causing damage both to his store and its contents. Later that month, the Columbia Enterprise carried a large I.H. Tate & Company advertisement that apologized to other area merchants for "the disastrous effect" that "cutthroat" and "ruinous" prices were almost certain to have on them, but there seemed to be no choice, the ad implied. "These Goods Must Go," it read further, calling attention to several bolts of material of all kinds as well as "notions, shoes, boots, clothing, hardware, and groceries" available "at prices that cannot be met by competition." It finished by directing would-be shoppers to "Call at once at the stand formerly occupied by W.H. Wood," which indicates that the store was so badly damaged it could not be re-opened right away and that Isaac had to operate out of a temporary location instead, at least for the time being. A Memorable Visit to Montgomery In the spring of 1886 Isaac H. Tate accompanied three other Columbia men on a trip to Montgomery, the capital of Alabama. The reason for their journey was to witness the dedication of the spot "on which the monumental tribute to the dead soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy should be placed" (adjacent to the state capitol) and to see and hear former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who had been invited to attend as a guest of honor (and who was also only three years away from the end of his life). A portion of their journey was chronicled in the Columbia Enterprise by one of the party (probably the editor, T.M. Espy), who wrote:

The clouds were black and threatening, the streets were wet and muddy, and the rainfall was steady throughout the day. Flags of all kinds were waving from the top of all the buildings in the city, and decorations of various kinds greeted the eye of the visitor from every view. The day was spent by our crowd in visiting the places of interest in the town. We saw many interesting and historical relics of the confederacy and those who figured conspicuously in it, which had been gathered up by the monumental association from different battle fields of the late war, and parts of the nation. The most prominent among those relics was a small mallet made from the wood of a tree that grew by the grave of Stonewall Jackson, and whose roots it is aid, "absorbed his dust." That evening, at 8 o'clock, Jefferson Davis arrived in the city by train from his home in Beauvoir, Mississippi, along with Montgomery Mayor Reese, Alabama Governor O'Neal, and five other distinguished gentlemen who had traveled with him in his special car. An enthusiastic crowd, a state militia escort, and a 100-gun salute by the Montgomery Artillery Company greeted the former rebel president at the station. Afterward, he and General Gordon, who had arrived a little earlier on a different train, rode together in a carriage to the Exchange Hotel-the same in which he had stayed the night before his February 1861 inauguration, while adoring throngs of Alabamians, no doubt including Isaac H. Tate and his comrades, stood in the rain and cheered the two men as they passed. A Northern reporter who witnessed the scene wrote:

The following day, the rain continued to come "down in torrents, filling the streets with mud ankle-deep, and making everything disagreeable." Then, a little before 1 p.m., "the sun succeeded in getting out so that it could be seen, and its beams flooded the city with all the warmth of a Southern sky." As the center of Montgomery filled with people, the day's events began to take shape.

No fewer than 3,000 people crowded the lawn in front of the Alabama state capitol (the largest number it would hold) as Davis alighted from his carriage and was escorted to the very same portico where he (Davis) had taken the oath of office as President of the Confederate States of America some twenty-five years earlier. By this time the rain had returned, requiring an umbrella to be held over his head as the aging former leader "walked up the incline leaning on the arm of Mayor Reese." Among the guests who sat with him" between the pillars of the central archway" was General and Mrs. Gordon, Mrs. Clement C. Clay, Governor O'Neal, and Minnie Davis, "the only child of her father" who accompanied "him on his trip to learn something of the feeling that is held for him here." When Davis rose to speak, the "applause that greeted him was so tumultuous that several moments elapsed before he could begin." Finally, after the cheering had subsided, he held forth in language that made it clear that neither he nor his adoring listeners, judging by their response, had learned the awful lessons of the past. Apparently, neither he nor one person present on that rainy April day had shed the outdated notions and reckless thinking that had led Southerners a quarter of a century earlier to attempt to forge a nation dedicated, not to the proposition of freedom-although that is how they miscast it, but instead to the perpetuation of chattel slavery. Unrepentant to the last, Davis spoke of that long-ago struggle as if were a glorious thing:

Following Davis's brief remarks, General Gordon embarked upon a much lengthier address, which was prefaced, and periodically interrupted by, cheers, applause, and "rebel yells" from the crowd. Afterward, a reception was held inside the capitol for the two men. Davis' "return to the Exchange Hotel, [at] about 5 o'clock, was a repetition of the triumphal scenes that attended his journey from there." Later that evening, he and his daughter, in company with General and Mrs. Gordon, went to the theater to see a performance that "was gotten up for the benefit of the monument fund." The following day, April 29, Davis and Gordon returned to the capitol grounds, this time to dedicate the site of Alabama's Confederate monument. We cannot be certain, however, if Isaac H. Tate and his friends stayed in town to witness it. According to one reporter: "Many of the visitors from out-of-town [had] returned to their homes." Indeed, there was such a mass exodus that "Special trains had to be run out this morning on all the seven roads centring [sic] here to accommodate those who left."

It seems more likely though, that the Columbia men stayed. Following the relatively "short and simple" ceremony, during which the cornerstone of the monument was set in place and Davis and Gordon both made speeches (Gordon's was the longest, lasting about an hour), the two guests of honor "went into the capitol," where Davis "received the Alabama veterans in a body." It is hard to conceive that Isaac H. Tate, who seems never to have lost pride in his Confederate military service, would have passed up an opportunity to see the former Confederate president up close and perhaps even to shake his hand and speak a few words to him. It is equally easy to imagine that he was among the cluster of old soldiers who "approached" Davis "with hats in hand" as he entered his carriage afterward, and who with "tear dimmed eyes…gave him an affectionate 'God bless you.'" Isaac H. Tate's Other Business Activities

Another one of Isaac H. Tate's property purchases is something of a mystery. On May 1, 1885, in partnership with William C. Koonce and W. H. Thompson, he bought slightly more than 69 acres of land, "known as the McCabe grove," in Calhoun County, Florida-located about 68 miles south of Columbia. Unfortunately, the purpose of this partnership, which appears to have been some sort of joint business venture, has been lost to history. In any event, Isaac H. Tate's connection with it was short-lived. On December 20, 1886, for the sum of $100, he sold his interest in the property to Koonce. On June 8, 1887, in consideration of the sum of $125, Isaac H. Tate sold his own father one-half interest in a house and lot on Broad Street, the original purchase of which seems to have gone unrecorded in county records. Isaac H. Tate seems also to have had at least a little interest in politics and public service. On May 5, 1887, the Columbia Enterprise reported that on Monday, "our town election was held and passed off quietly." John T. Davis was elected mayor and Isaac H. Tate, who received 104 votes, was chosen to serve as one of Columbia's four city councilmen. Isaac H. Tate's 1887 Visit to New York City

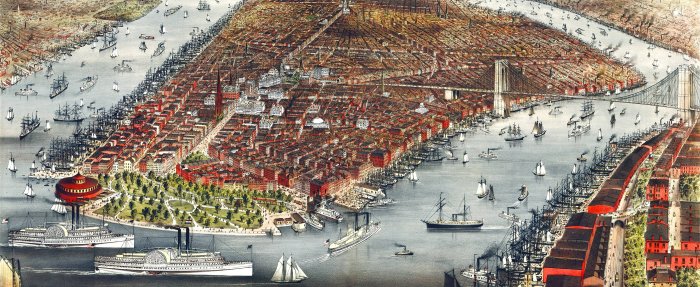

In mid-summer 1887, Isaac H. Tate and three other men-Dr. F. I. Moody, M. W. Kelly, and John R. Kelly ("of Newton" added the Columbia Enterprise)-made an 18-day trip to New York City, to buy "fall and winter" merchandise. Although there were other routes they could have taken, it seems most likely that on the day of departure--Sunday, July 24, 1887--the four men traveled by horse or carriage to Blakely, Georgia, a distance of only fourteen miles, where they boarded a train bound for Savannah, Georgia. (A railroad did not reach Columbia until 1889.) Thanks to The Columbia Enterprise, we know they traveled the rest of the way by sea. On either July 25 or 26 (unless they also had business in Savannah, which would have delayed their departure) they continued their journey aboard one of six passenger vessels operated by the Ocean Steamship Company of Savannah. In all likelihood, they arrived in New York on Thursday, July 28, following a "rough" two-day voyage aboard the steamship City of Savannah.

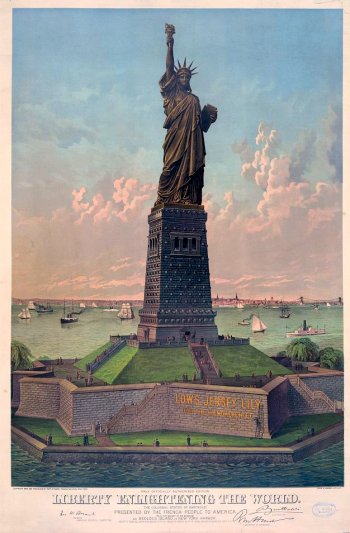

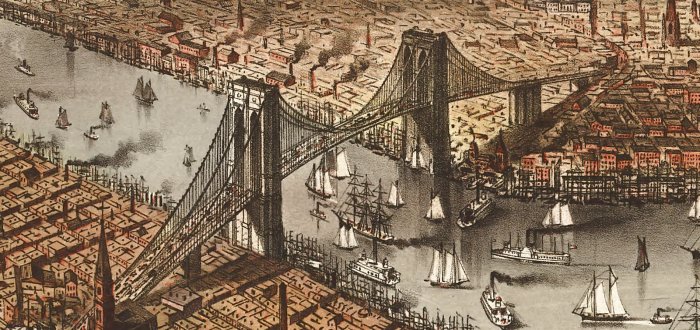

If so, it is also not too much to imagine that he would have visited the Statue of Liberty, which had been erected only a year earlier on what was then still called Bedloe's Island, and which would have still been copper colored, like a new penny, having not yet acquired the light green patina it has today. Standing over 500 feet above New York harbor, what a fantastic sight it must have seemed! Isaac might also have walked across the 5,989 foot long Brooklyn Bridge, which had only been completed four years earlier, and almost certainly he marveled at the many tall buildings that rose to the sky between another great wonder-the elevated railways that crisscrossed the city. Perhaps he found it all just a little overwhelming, having never seen a city of that immensity before. Federal census records reveal that in 1880 New York City had nearly as many residents as the entire state of Alabama! By 1887 that number, slightly more than 1,200,000, had dramatically increased, thanks largely to immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. That too was almost certainly something new and different to Isaac H. Tate-the great mass of humanity arriving at Castle Garden on the tip of Manhattan (Ellis Island was not yet built), pouring off ships from nearly every country on the globe, all speaking different languages and dressed in what probably seemed like strange costumes. In Alabama, people were either black or white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. But here, in New York, there were all kinds of people-Roman Catholics from Poland, Hungary, Italy, and Bohemia, not to mention Jews from Russia, as well as Greeks and Turks.

Isaac and one his companions, John Kelly, apparently left New York ahead of the other two men, returning to Columbia on Wednesday, August 10, "looking fresh and lively." The Columbia Enterprise also reported that they had "a lively time while gone." Owing to another comment in the paper, namely that Dr. F. I. Moody and M. W. Kelly were returning "by way of Savannah" and "will here perhaps today [August 11]," it appears that Isaac and John Kelly took a different route home, possibly by steamship to Mobile, although the newspaper does not specifically say so. A few days later, the Columbia Enterprise included a statement from I. H. Tate & Co. that read: "Having bought our goods in the New York market, and got them very cheap, we are prepared to sell goods closer and cheaper than they have ever before been sold in this city." Another notice in the same edition of the paper added: "I. H. Tate & Co. have a large lot of goods on hand that they are offering below actual New York cost." The same issue observed too that Isaac's father and stepmother, Harrison and Mary C. Tate "left on Saturdays [sic] [steam] boat to visit relatives in Lee County. They will be gone several weeks." The Tate Family Moves To Texas In 1860, Isaac H. Tate's sister Minerva Jane married a Lee County farmer named James Dunlap Smyrl. In 1869 the young couple and their daughter Laura had moved to East Texas, where they and their children (three of whom were born in Texas) took up residence in the Cherokee County community of Jacksonville, later moving to Larissa. "There," according to one of their descendants, "J. D. ran a mercantile business, served as Most Worshipful Master of the Masonic Lodge and served as the clerk for the Salem Baptist Church." About 1878, Isaac's brothers John and James and their families also moved to Texas, settling in Cass County, on the Texas-Louisiana border. Unfortunately for Isaac H. Tate, who had thus far remained in his native Alabama, there were far too many merchants in the little town of Columbia, all vying for (and no doubt extending credit to) the same small pool of customers. By 1888 he was deeply in debt. At forty-four-an age when most men are fairly well settled in life, he was giving serious consideration to joining his brothers and sister in Texas. On March 15, 1888, the Columbia Enterprise reported that the struggling shopkeeper had "returned last Friday from an extended trip to the West. He visited Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas, and reports having had a delightful trip. He was very favorably impressed with the country." It was also noted "Miss Ida Smyrl, of Jacksonville, Texas, came home with her uncle I. H. Tate, and we are pleased to learn that she will spend some time here." Unfortunately, the very same issue also listed no fewer than five recently filed lawsuits against Isaac H. Tate, two of which were reported settled out of court. In the other three cases, juries returned a verdict in favor of the plaintiffs, ordering Tate to pay in one case $1,862.82, and in another, $716.23. The amount in the third case was not noted. On Sunday, July 1, 1888, Isaac H. Tate and his family, accompanied by his niece, Ida Smyrl, departed Columbia aboard a steamboat that would take them at least part of the way, said the Columbia Enterprise, on their journey to "their new home in Texas, perhaps Jacksonville." According to family lore, what little money was left over after settling Isaac's debts was sewn into Sarah Tate's petticoats for safekeeping. The amount and nature of any household effects they might have taken is unknown. All we can be sure that they took was a "crazy quilt" that Sarah had recently sewn together from scraps of cloth and a meager collection of photographs, including one of Isaac in his Confederate uniform, taken when he was only seventeen. At the time of their departure, the family consisted of Isaac and thirty-six year old Sarah, ten-year old Henry Harrison Tate, his fourteen-year old sister Hettie, eight-year old Mamie, and little two-and-a-half year old Alice. Sarah, it should be noted, was almost nine months pregnant with her twelfth child! It is not clear how far the family traveled by steamboat. Certainly, they could not have gone all the way to East Texas by that mode. Many decades later, Alice Tate would tell her grandchildren that she and her family made the journey in a mule-drawn wagon, but of course she was much too young at the time to have any actual memory of it. Unfortunately, the Columbia Enterprise did not indicate which direction the steamboat took them. If they went south to the Gulf of Mexico, they might have taken a steamship from Pensacola, Florida to either New Orleans or Galveston and then traveled either by train or wagon from one of those places to Jacksonville, which is in Cherokee County in East Texas. Another possibility is that they went north, by steamboat to Eufaula, from where they took a train to Texas, which seems most likely in view of the fact that on July 17, only two weeks after they left Alabama, Sarah gave birth in Jacksonville to baby Roy Neil Tate, probably at the home of James and Minerva Smyrl. If they had traveled by wagon they could not possibly have reached Texas so quickly. The Unsettled Years (1888-1891) From July 1888 until January 1891, a period of nearly two-and-a-half years, Isaac and Sarah Tate and their children resided in no fewer than five different Texas communities--Jacksonville, San Marcos, Rusk, New Birmingham, and Vernon--apparently unable to either make a living in any of them or unable to make up their minds where they wished to settle. For some unknown reason the family left Cherokee County almost immediately after baby Roy was born and moved south to San Marcos, the seat of Hays County--located about more than 230 miles from Jacksonville, halfway between Austin and San Antonio. In San Marcos Isaac attempted to launch a new retail business. On August 16 the San Marcos Free Press helpfully announced that "Mr. S. A. Tate having purchased the stock of Mr. Donohoo, may now be found at the old stand of the latter, south side of the public square, with a full choice of family groceries." The misidentification of Isaac as "Mr. S. A. Tate" was almost certainly due to Sarah being named on the deed as purchaser of the property, which was probably done to keep any of Isaac's Alabama creditors from getting their hands on his property before he had a chance to make it pay.

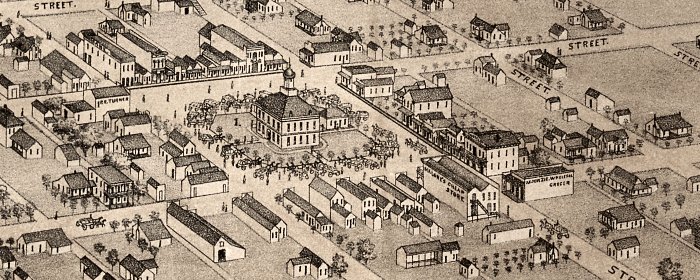

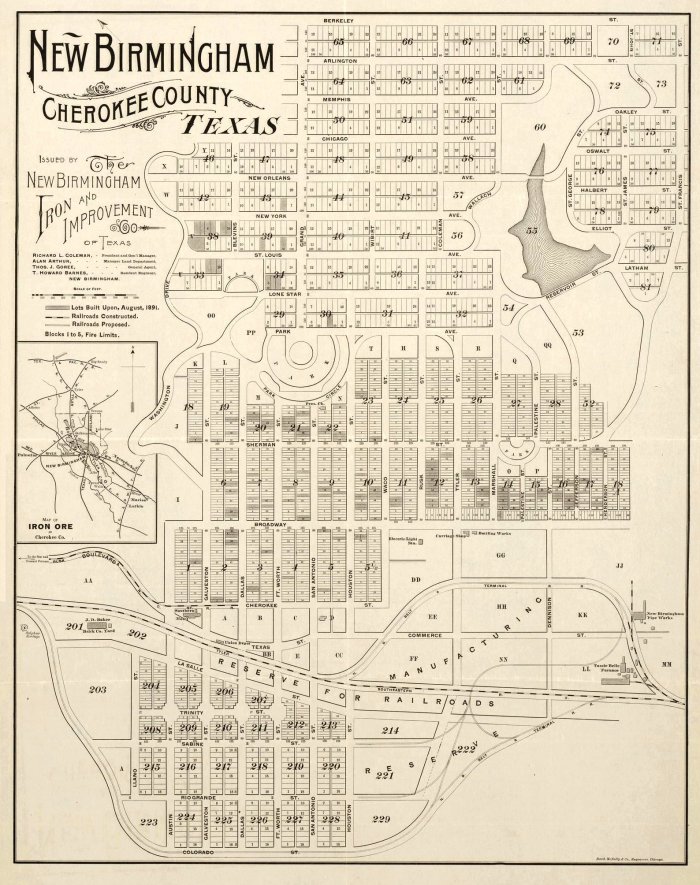

A week later, on August 23, the newspaper gave Isaac a little more publicity, reporting, "Mr. Tate, the new grocery dealer, at Donohoo's old stand, is now well organized and equipped for business," adding: "Give him a trial." Sadly, the same issue also announced that "the infant child" of "our new townsman" had recently died; the sad event having occurred on August 17, exactly one month after baby Roy was born. There seems to be no record of where the child was buried. On September 20 the paper announced "Mr. Tate has moved to the Mosher place, now the property of T. C. Johnson." It was not clear however, whether the move referred to his home or business, although the latter seems more likely. Then, in mid-November it reported "Mr. Tate has sold out his grocery store to our young friends Charlie Steele and Willie Joyce, whom we wish great success." The writer added: "Mr. Tate informs us that he has not decided to his future." It appears that following Isaac's second business failure in less than one year, the Tate family returned to Cherokee County, where they may have lived a while at Rusk while Isaac made a brief trip to Alabama to visit his father and stepmother. Sometime in early 1889 they moved again, this time to nearby New Birmingham, a brand-new community where two entrepreneurs, Anderson Blevins and W. H. Hamman, had recently started a business called the Cherokee Land & Iron Company in order to capitalize on the 20,000 acres of iron ore-rich land they had purchased with the help of investors in New York and St. Louis. Whether Isaac went to work for Blevins and Hamm in their newly-constructed smelting plant or made another attempt to start a small retail business is unknown but it is a certainty that the Tate family was living in New Birmingham, Texas when Isaac made another short trip to Columbia, Alabama in July 1889.

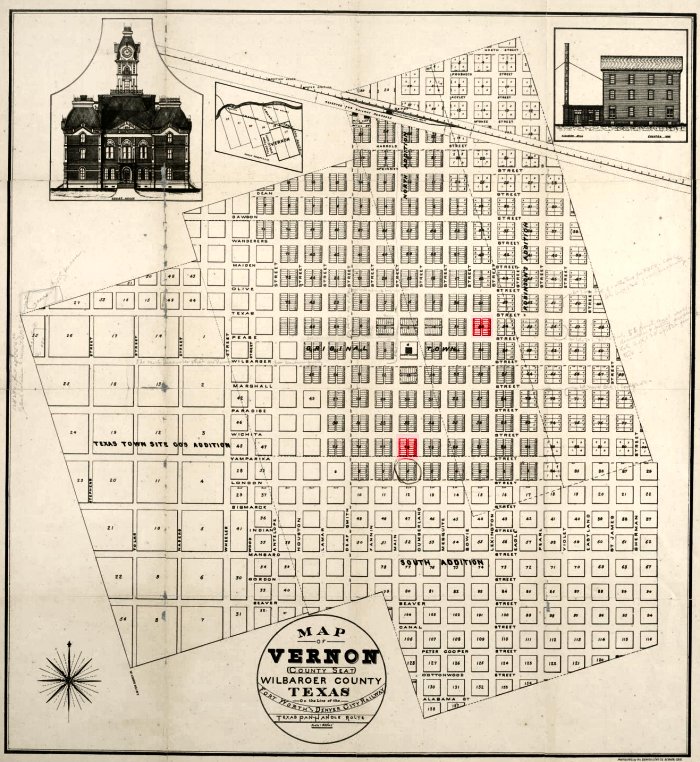

It is easy to see why Isaac and Sarah decided to move to New Birmingham. The place seemed full of possibilities, at least for a while. On May 28, 1889 Thomas R. Connor, "past grand master of the masons of Texas," laid the cornerstone of the Cherokee County courthouse during an "impressive" ceremony in Rusk that was "witnessed by people from all parts of the state." That same day, there was a "grand excursion" to New Birmingham, where "everything in a business way" was "at a high tension" and the "sale of city lots…went beyond the expectations of the most sanguine, purchasers from all parts of the United States being here in numbers." The boom times and rapid growth of New Birmingham makes it more difficult to comprehend why Isaac and Sarah Tate decided to leave Cherokee County sometime during the late summer of 1889 and move again, this time to the North Texas town of Vernon, located about fifty miles west of Wichita Falls. Whatever reason they might have had has been lost to history. As far as it is known, there were no friends or family members living in Vernon at the time, as there were in Cherokee County. Whatever caused them to leave New Birmingham, in the end the move turned out to be a good decision. Although the town grew rapidly and thrived for about five years, it declined nearly as quickly. Today New Birmingham is a "ghost town" with very little left of what was briefly a busy, bustling community. Vernon was likewise on a boom at this time. In October 1888 the Dallas Morning News reported that the "big roller flouring-mill is going up and will be the best equipped and finished…in north west Texas." In another story, which told of the opening of a new iron bridge across the Pease River, the News remarked further: "Vernon is enjoying a genuine building boom. The saw and hammer are heard on all sides, and not a single vacant house in town." A later report entitled "Vernon's Growth" highlighted the construction of a new factory, a steam brickworks, the expansion of the city's streetcar line, and the numerous brick buildings that being erected." The report continued:

On September 4, 1889, Isaac and Sarah purchased (in Sarah's name only) two city lots (nos. 9 & 10 in Block 78) situated three blocks south of the Wilbarger County courthouse, for $175. Whether they lived in a house on this property, which was located at the northeast corner of Cumberland and Wichita streets, or simply bought it as an investment is unknown but they did not hold on to it very long. On January 21, 1890, in exchange for $1,000 in cash and promissory notes, they sold the two lots to a Mr. G. W. Williams, making a profit of $825! On May 9, 1890, after Williams had finished paying off the notes in full, the couple relinquished the property to him. About two weeks later, on February 5, 1890, the couple (again in Sarah's name only) purchased two more city lots (nos. 7 & 8 in Block 60), four blocks east of the county courthouse. It is more likely they actually lived in a house on this property, for which they paid $400, owing to the fact that they remained in possession of it until January 1, 1891, although they actually sold it on October 28, 1890 for $900 ($150 cash and the remainder in promissory notes) to Mr. E. Krohn.

Sadly, during the family's sixteen-months-long sojourn in Vernon, from the beginning of September 1889 through the end of December 1890, there were two untimely deaths in the family. The first occurred on November 5, 1889 when Isaac's sister, Minerva Tate Smyrl, died and was buried at Jacksonville. Chances are, her bereaved brother went back to Cherokee County to attend her funeral. Minerva was only forty-seven years-old when she died. This period was also marked by two happier occasions. The first of these was the birth of Sarah Tate's thirteenth child-a little girl who was named Bessie Fay-on March 2, 1890. Then, two weeks later, on March 14, sixteen-year old Hettie Tate was married to Vernon real estate developer John W. Abbott. This joyous event was unfortunately overshadowed by the death of Bessie Fay on June 15. Less than five-months old, she was buried at Vernon's Eastview Memorial Park, where today her grave shares a marker with Hettie and John W. Abbott's first two sons, both of whom also died in infancy, in 1891 and 1892 respectively. None of their names are given on the marker, a long low piece of white marble. Bessie Fay is identified only as "Infant Dau. of Mr. & Mrs. I. H. Tate."

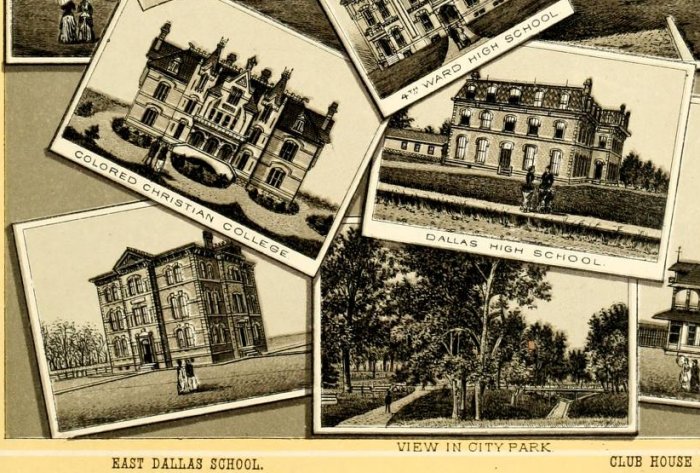

The Tate Family Moves to Dallas In January 1891, Isaac and Sarah Tate made their last major move. Leaving Hettie behind in Vernon with her new husband, they took their remaining children-Henry, Mamie, and Alice-and went to live in Dallas. Again, the reason for this move has been lost to posterity. Perhaps this time they traveled in the mule-drawn covered wagon that Alice seemed to remember years later, although it is more likely they traveled by train. In 1890 Dallas was nothing like the sprawling "metroplex" it is today but compared to Columbia or Vernon it must have seemed enormous, at least to Sarah and the children. (Isaac, of course, had seen New York.) Indeed, it was the big city in 1890-the largest in Texas, with a population of 38,067. (San Antonio was then the second largest city and Galveston, previously number one, had slipped to third place.) There were 300 saloons and beer halls and 572 streets. The most prestigious part of town was at the intersection of Wolfe and Maple streets. On the northwest corner, where the Maple Terrace Hotel now stands, the Dilley family mansion was finished in 1890 at a then unheard of cost of $40,000! Soon after, Maple, Fairmount, Routh and Cedar Springs were also lined with expensive homes. In the spring of 1890 the then-separate town of East Dallas had been annexed by the larger city of Dallas (which accounts for how Dallas came to be the largest city in the state). The East Dallas City Hall, at the corner of Gaston and College, was afterward turned into a school where Alice Tate was later a student. Dallas still had its rural side in those days; Trades Day, or First Monday, was held every month at Chenoweth Brothers feed storage barn and also at Dallas' largest wagon yard, located at Houston and Commerce (site of today's Terminal Annex). Farmers, horse traders, mule-breeders and boys spilled into the alleys and jammed the streets around the site. Today's trendy "West End" consisted mainly of the factories and warehouses of a large farm implement industry. During their first two decades in Dallas the Tates lived at a succession of addresses, which tells us they were renters. Their first home was located at 821 Commerce Street, in what is now the "Deep Ellum" section of the city. They were living there when Isaac received a telegram informing him that his father had died on January 18, 1891 at his home in Columbia, Alabama. There seems to be no record that any member of the family returned "home" for the funeral, but we do know that on April 11, 1891, Isaac inherited $200 from his father's estate, for which he sent his stepmother Mary a receipt. The family's second address in Dallas was 242 Beaumont Street, not far from City Park in South Dallas. Although the Tates lived in a working class section, it was adjacent to a neighborhood full of large comfortable homes owned by some of Dallas' more successful merchants, such as the Sanger brothers, who owned and operated the city's best known department store.

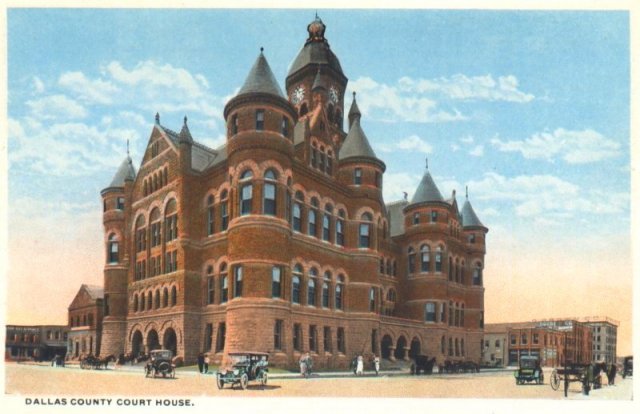

From about 1892 to 1893 the Tates lived just north of today's downtown business district, at 536 San Jacinto. Sarah Tate's last child, a little girl named Ruby, was born soon after the Tate family arrived in Dallas. Born on October 16, 1891, she died less than three years later, on April 18, 1894. The cause of her death is unknown. At the time of her passing, the family resided again in South Dallas-at 648 (now #2508) South Harwood, between Coombs and Clarence Streets. Around this same time (1894) Isaac went back into business for himself-apparently for the last time, and only briefly-selling vegetables at 336 (now #1504) Elm Street in the heart of today's downtown Dallas (near the northwest corner of Elm and Akard Streets). The current use of the site is unknown. During this same period, Isaac's son Henry Harrison, then seventeen years old, worked as a machine hand at the Dallas Box and Woodwork Company on Main Street. Before 1895 the Tate family had moved yet again, this time to 482 Browder Street (now #1814). By this time, young Henry Harrison Tate was working as a clerk and his father, it appears, was no longer in the grocery business (although his actual occupation at this time is unknown). The Browder Street address was in South Dallas-once again near City Park. Between 1897 and 1902 the family resided at 282 (now #3100) Floyd Street, at the corner of Oak and Floyd-just slightly north of today's downtown Dallas. During this period the Dallas Box and Woodwork Company again employed Isaac's son. Isaac himself was a "representative" of The Dallas Weekly Record, a newspaper that is now long defunct. Its offices were located at the southeast corner of Commerce and Houston Streets near the "Old Red" courthouse, which still stands today. Exactly how Isaac "represented " the paper isn't known. Perhaps he sold advertising, or copies of the newspaper itself. Not long after coming to live in Dallas, Isaac had become a member of the Sterling Price Camp of the United Confederate Veterans. This group had been formed in 1889 and counted among its membership some of the most prominent members of Dallas' civic and business community. One of the most outstanding of these was General "Old Tige" Cabell who also served for a time as Mayor of Dallas. General Cabell, each New Year's Eve, would hold an open house for the veterans in his own home. His daughter, Katie Cabell Curry, was very active in the Daughters of the Confederacy-an organization that was very supportive of the veterans.

In 1898 tragedy struck the Tate family. Henry Harrison Tate (seen in photo left)--Isaac and Sarah's only living son--died on November 6 in Lexington, Kentucky. According to family lore, he traveled there with friends to see the horse races and was kicked or trampled by a horse, resulting in fatal injuries. However, the official death certificate says nothing about such injuries. It states simply that he died in the Protestant Infirmary of pneumonia. He was only twenty-one years of age and unmarried. Unfortunately, details regarding this incident are lacking. Neither the Lexington nor Dallas newspapers carried any report. His father had the sad task of traveling alone to Lexington, probably by train. Almost certainly due to a lack of money, Isaac had his son buried in Kentucky rather than bring his body home to Dallas. Nor could he afford a headstone. Henry Harrison Tate's grave, in the Lexington City Cemetery, remains unmarked to this day.

During the 1890s Mamie and Alice Tate attended the Dallas schools. Their grades reflected their intelligence and hard work. Both were students at the East Dallas School (later called Stephen F. Austin), located near their home. Following graduation from Dallas' Bryan High School in 1898, Mamie went on to become the first member of her family to attend college. Amazingly, she not only attended classes at North Texas Teachers College in Denton but also the University of Texas in Austin and in 1904 she was briefly enrolled at the University of Chicago! What makes this achievement remarkable is that she did so during an era when only a very few men, much less women, received a post-secondary education-and especially a woman from a working-class family! How she found the money for college is unknown but it is unlikely that her parents paid for it. In all probability, she won scholarships.

In the fall of 1900 Mamie became a "supernumerary" at Stephen F. Austin School, at a salary of $15 per month, before being promoted to teacher in 1901. Alice went on to attend high school but apparently never graduated. In April 1902, Dallas hosted a grand Confederate Veterans Reunion at the State Fairgrounds (today's Fair Park). Most of the activities were centered around the old wooden exposition building, which stood on the site of the present Centennial Building. Isaac H. Tate, as a member of the local camp, was no doubt a host delegate to the event, which attracted thousands of ex-Confederates from all over the South. It lasted for several days. About 1903 the Tate family moved to 215 Floyd Street (now #2815), between William Tell and Germania Streets, where they lived until about 1905 or 1906. In 1906 Isaac was made a delegate to the Confederate Reunion held in New Orleans. That same year (or possibly in late 1905) the family moved for the last time, to a house that Mamie bought at 1013 Main Street in East Dallas, just a few blocks from Fair Park. (The address was changed in 1913 to #3905.) This was the home in which Isaac and Sarah Tate spent the remainder of their days. At the time they moved in, Isaac was sixty-two and Sarah was about fifty-four. Mamie, who never married, lived with her parents. Located near the corner of Washington and Main in what is now called "Deep Ellum," the house was long ago torn down. The address today is the site of a retail business. 1906 also witnessed the March 18th marriage of Alice Tate to a young man named Herman Butler. After their marriage, Herman and Alice lived at 235 Gaston Avenue, not far from Alice's parents' home on Main Street. Throughout their marriage, reflecting the close ties Alice had with her parents, Herman and Alice Butler never lived far from Isaac and Sarah Tate. In 1901 Isaac had been employed as a laborer with the city street department but during most of the first decade of the twentieth century he worked as a carpenter, literally helping to build Dallas. On some jobs he worked with his son-in-law Herman, and also possibly Herman's father Will Butler. Isaac and Sarah's old age seems to have been relatively uneventful, probably filled with routine. Isaac corresponded with friends and relatives back "home" in Georgia and Alabama. It appears they may have made a trip back east to visit Isaac's youngest brother, "Tommy," who lived in or near Columbus, Georgia. They might also have gone back to visit Columbia, Alabama where Harrison Tate, who had died in 1891, was buried. It is not hard to imagine that Isaac attended the State Fair of Texas each year on Confederate Veterans Day, which was an annual event. For most of the first two or three decades of the twentieth century, ex-Confederates comprised a large portion of Dallas' elderly and were generally well respected by the community at large. Isaac's children were particularly proud of "Papa" and his service to the Southland. In 1914, Isaac wrote to Confederate Veteran magazine. A plea for his fellow ex-soldiers to write to him was carried on page 239 of the May 1914 issue. It read:

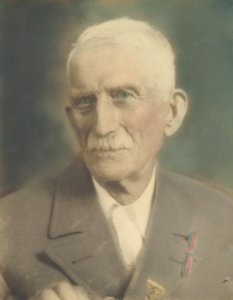

I. H. Tate's Final Years By the mid-1920s Isaac and Sarah were getting on in years. Sarah, called "Gustie" by her husband (because of her middle name Augusta), was reportedly a small woman with a big heart. Her granddaughter, Margaret Butler Ficklin, remembers Sarah as "a little bitty thing" and "the sweetest woman" you would ever want to meet. Sarah very rarely left home, even to go to church on Sundays. On March 29, 1928 she died at home at 3:25 AM. She was seventy-six years old. A year earlier, Isaac Tate had purchased a plot in Forest Lawn Cemetery, which was then far out in the countryside north of Dallas, beyond Bachman's Lake. Today, the site is located at the southwest corner of the busy intersection of Harry Hines Blvd. and Walnut Hill Lane. It was here that Sarah Tate was laid to rest. "Grandpa" Tate, as Margaret Butler and her siblings called Isaac, lived on a few more years after his wife's death. He was a relatively tall man, at least six-feet, but in old age he walked with a pronounced stoop, at least at home. When going out, he would walk stooped over to his front gate. As he opened the gate and stepped out on to the sidewalk, he would straighten his back and walk out tall, proud and erect, his back like a ramrod. Isaac never spoke to his grandchildren about his experiences in The Civil War. If they were around when he and old friends began to reminisce, the children would be shooed away and told to go play. He was a religious man and read his Bible faithfully each day. The Tate house had a big porch on all sides and Isaac kept chairs there. On the front door he had a sign that said he read his Bible from one o'clock to two o'clock and if anyone came by to call on him at that time, the sign instructed them to take a chair and wait. He kept this habit very strictly. Yet he was reticent about discussing religion with anyone. To him, it was a private matter. Unlike Sarah, he attended church regularly and was a member of the Grace Methodist Church for over thirty years. Seemingly an unlikely candidate, Isaac was the first member of his family to fly in an airplane! Sometime, probably in 1931, he went to Dallas' Love Field airport for a half-hour flight over Dallas. An article in a local newspaper reported:

A photograph of the old man accompanied the article. How he came to take the ride is unknown.

His stay was very brief. Perhaps he sensed he had little time left to live and just wanted to die at home. For whatever reason, Isaac wrote a letter to the Comptroller of the Confederate Home on September 30th, which said in part, "I am going back to Dallas to stay." He was discharged the next day, October 1, 1931. He then returned home to Dallas, having spent less than two months in Austin. However, on December 4 he was readmitted, possibly for medical treatment. His stay the second time was longer, until April 1st, 1932 when he was allowed to go home again. That trip was his last. Less than two weeks later, on Tuesday, April 12th Isaac Henry Tate died at his home on Main Street in Dallas. He was 87 years, 5 months, and 12 days old. The following day, April 13, 1932, the old man was laid to rest next to his wife at Forest Lawn Cemetery, following services held at the Ed. C. Smith and Bros. mortuary. He was buried wearing a gray uniform -- an old Southern soldier to the end. A large stone marked "TATE" was erected above his grave, in addition to the smaller ground level stone bearing his name and the years of his life's beginning and end. The large family he left behind attended his funeral; a number of his grandsons were his pallbearers. During his long life Isaac Tate not only witnessed but participated in some of the great events of the history of the United States. He also lived to see great technological advances that were mere fantasies at the time of his birth. A individual who did not believe that a forty-four year old man was too old to pursue a dream, he left the state of his birth to seek a better life in a the fledgling North Texas metropolis of Dallas. His descendants live there still.

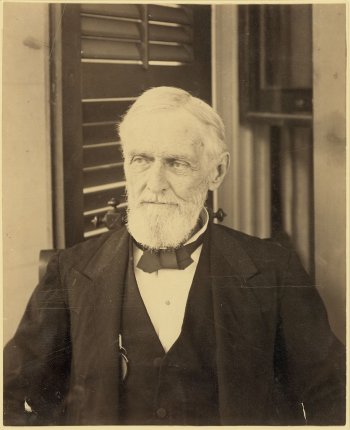

Photograph of Jefferson Davis (above), courtesy Library of Congress. Photograph of Isaac H. Tate in old age (above), from author's personal collection.

This website copyright © 1996-2011 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |

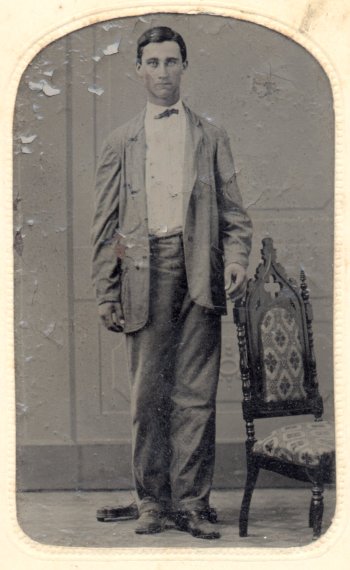

At home in Alabama, the twenty-one year old former soldier (shown right in an undated postwar photograph) married his stepsister, Sarah Augusta West, on November 19, 1865. A month later, on December 23, the new Mrs. Tate, a native of Harris County, Georgia, celebrated her fourteenth birthday.

At home in Alabama, the twenty-one year old former soldier (shown right in an undated postwar photograph) married his stepsister, Sarah Augusta West, on November 19, 1865. A month later, on December 23, the new Mrs. Tate, a native of Harris County, Georgia, celebrated her fourteenth birthday. Nine of the Tate children did not even reach school age, their span of life ranging from one month to about three years. The only one to survive infancy but not to reach maturity was Isaac and Sarah's first child-a daughter named Manerva (or Minerva) who was born in 1866. Manerva died in 1875, just a few months short of her ninth birthday.

The children who survived to adulthood were Hettie, born in 1873; Henry Harrison (the son who died at age twenty-one), born in 1877; Mary Leona, or "Mamie," born 1879; and Alice May, born 1885. The three daughters all lived a normal or slightly longer than normal lifespan. Presumably, Henry Harrison Tate might have done the same had he not met with an accident.

Nine of the Tate children did not even reach school age, their span of life ranging from one month to about three years. The only one to survive infancy but not to reach maturity was Isaac and Sarah's first child-a daughter named Manerva (or Minerva) who was born in 1866. Manerva died in 1875, just a few months short of her ninth birthday.

The children who survived to adulthood were Hettie, born in 1873; Henry Harrison (the son who died at age twenty-one), born in 1877; Mary Leona, or "Mamie," born 1879; and Alice May, born 1885. The three daughters all lived a normal or slightly longer than normal lifespan. Presumably, Henry Harrison Tate might have done the same had he not met with an accident. On Wednesday, July 6, 1881, a notice appeared in the Columbus [Georgia] Examiner, reporting "Judge Harrison Tate and his son Mr. Isaac Tate will soon leave Opelika and move to Columbia, Henry County, Ala., where they propose to engage in the grocery and supply business." This was actually old news. By the time the notice appeared in the paper, they had already moved to Henry County.

On Wednesday, July 6, 1881, a notice appeared in the Columbus [Georgia] Examiner, reporting "Judge Harrison Tate and his son Mr. Isaac Tate will soon leave Opelika and move to Columbia, Henry County, Ala., where they propose to engage in the grocery and supply business." This was actually old news. By the time the notice appeared in the paper, they had already moved to Henry County. The time set for the march to the Capitol was 2 o'clock, but fully an hour before that every window on the route had a half dozen heads in it, and every porch was taxed to its full capacity. The streets too, were thronged. The crowd [which almost certainly included I.H. Tate and his fellows] waited patiently for the blast of the trumpet that told them that Mr. Davis had started. A cavalry troop, their yellow and gold trimmings glittering in the sunshine, then dashed into the square, on which the Exchange Hotel fronts. Then came the Montgomery Greys, escorting Mr. Davis and Mayor Reese. The carriages with the other guests were escorted by the Independent Rifles, another local military company.

The time set for the march to the Capitol was 2 o'clock, but fully an hour before that every window on the route had a half dozen heads in it, and every porch was taxed to its full capacity. The streets too, were thronged. The crowd [which almost certainly included I.H. Tate and his fellows] waited patiently for the blast of the trumpet that told them that Mr. Davis had started. A cavalry troop, their yellow and gold trimmings glittering in the sunshine, then dashed into the square, on which the Exchange Hotel fronts. Then came the Montgomery Greys, escorting Mr. Davis and Mayor Reese. The carriages with the other guests were escorted by the Independent Rifles, another local military company.

Although the general store on Bond Street seems to have been his principal business endeavor, it appears that Isaac H. Tate also speculated in real estate. On December 31, 1886, he purchased a house and lot on Church Street from one W. B. Deal, paying a little more than $258 for the property. A little more than ten months later he sold it to Mr. J. D. Weld for nearly $400 more than he paid.

Although the general store on Bond Street seems to have been his principal business endeavor, it appears that Isaac H. Tate also speculated in real estate. On December 31, 1886, he purchased a house and lot on Church Street from one W. B. Deal, paying a little more than $258 for the property. A little more than ten months later he sold it to Mr. J. D. Weld for nearly $400 more than he paid.

We can only guess how Isaac and his companions filled their time during this visit to America's largest city, apart from purchasing merchandise, nor do we know the name of the hotel they chose, but in all likelihood this was Isaac H. Tate's first and only visit to the city we now call "The Big Apple." It therefore seems probable, even likely, that he made at least a little time for sightseeing.

We can only guess how Isaac and his companions filled their time during this visit to America's largest city, apart from purchasing merchandise, nor do we know the name of the hotel they chose, but in all likelihood this was Isaac H. Tate's first and only visit to the city we now call "The Big Apple." It therefore seems probable, even likely, that he made at least a little time for sightseeing.

In 1897 the Daughters of the Confederacy unveiled a grand monument to the Confederate Veterans in City Park. None other than the widow of Confederate President Jefferson Davis also attended the unveiling, witnessed by literally thousands of Dallasites. Isaac Tate, as staunch a Confederate as any, was surely in attendance, along with members of his family.

In 1897 the Daughters of the Confederacy unveiled a grand monument to the Confederate Veterans in City Park. None other than the widow of Confederate President Jefferson Davis also attended the unveiling, witnessed by literally thousands of Dallasites. Isaac Tate, as staunch a Confederate as any, was surely in attendance, along with members of his family.

In 1915 Isaac had applied for and began receiving a Texas Confederate Veteran's Pension. In 1931, the same year in which he took the airplane ride, he applied for admission to the Texas Confederate Home in the state capital, Austin. Before he could be admitted, he had to submit to a physical examination. It found him to be about five feet, seven inches tall (obviously, he had "shrunk" with age), weighing about 100 pounds. He appeared to be "debilitated." His main health problems were that he had "difficulty at times in starting urine" and "a mild myocardial degeneration." He also had a suspected malignancy of the stomach as well as a hernia. For the latter, he already wore a truss. The doctor who examined him wrote that Isaac was, "A dear old man, who mental facilities are clear. For several months he has had pains in his stomach, nausea and vomiting, fermentation, loss of weight, etc.". Isaac's application was approved and he entered the home on August 13, 1931.

In 1915 Isaac had applied for and began receiving a Texas Confederate Veteran's Pension. In 1931, the same year in which he took the airplane ride, he applied for admission to the Texas Confederate Home in the state capital, Austin. Before he could be admitted, he had to submit to a physical examination. It found him to be about five feet, seven inches tall (obviously, he had "shrunk" with age), weighing about 100 pounds. He appeared to be "debilitated." His main health problems were that he had "difficulty at times in starting urine" and "a mild myocardial degeneration." He also had a suspected malignancy of the stomach as well as a hernia. For the latter, he already wore a truss. The doctor who examined him wrote that Isaac was, "A dear old man, who mental facilities are clear. For several months he has had pains in his stomach, nausea and vomiting, fermentation, loss of weight, etc.". Isaac's application was approved and he entered the home on August 13, 1931.