|

Louis Du Bois and the Blanchan and Crispel Families I am descended from Louis Du Bois by virtue of the marriage of my great-grandfather William Newton Jenkins to Emmerine J. Morrison, daughter of Isaac Fisher Morrison, son of Samuel H. Morrison, son of Elizabeth Haycraft Morrison, daughter of Margaret Van Meter Haycraft, daughter of Jacob Van Meter, son of John Van Meter, son of Jooste Jans van Meteren and his wife Sarah Du Bois, who was the daughter of Louis Du Bois, also known as "Louis the Walloon," an early-day immigrant to America. I am also a Blanchan descendant by virtue of the marriage of Louis Du Bois to Catharine Blanchan, daughter of Mathése Blanchan. Louis Du Bois, a son of Chrétien Du Bois," was born on October 27 in either 1626 or 1627 at Wicres, a small village located in the district of La Barrée, near Lille, in the Artois region of Flanders. Although this spot is now within the boundaries of France, at the time of Louis Du Bois' birth it was part of the Spanish Netherlands, the largest portion of which later became the modern-day nation of Belgium. The Du Bois family were Walloons, a mostly Celtic people with their own unique dialect. The famed nineteenth-century historian William Cullen Bryant described them thusly:

Not all the Walloons went to the free Netherlands (also known as the United Provinces) to escape persecution. Some, explains author Charles W. Baird, sought refuge in a portion of what is now the modern-day nation of Germany:

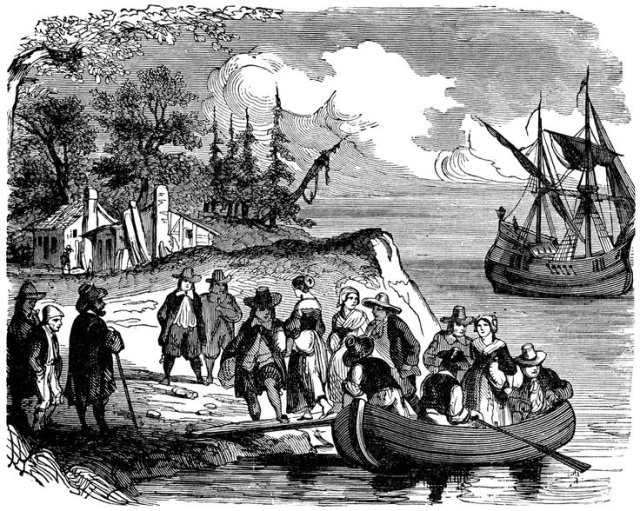

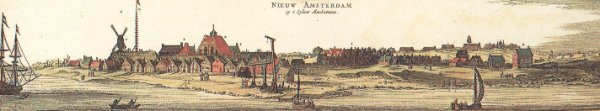

"Long before this," adds Baird, "a little colony of Walloons had come to settle within the hospitable territory of the Palatinate, at Frankenthal, only a few miles from Mannheim, its capital." In the late 1640s however, it was Mannheim, that "now became the home of many French refugees," including Louis Du Bois and the men who would become, respectively, his father-in-law and brother-in-law - Mathése (or Matthew) Blanchan and Antoine (or Anthony) Crispel, who were also natives of Artois. Baird also tells us that it was in Mannheim on October 10, 1655, at the age of about twenty-eight, that Louis Du Bois married Catharine, a daughter of Mathése Blanchan, whom author Ralph Le Fevre describes as "a burgher of that place." It is believed that Catharine was about twenty years of age at the time, having been born about 1635 in Artois. In the years immediately following their marriage, Catherine gave birth, at Mannheim, to two sons: Abraham, born 1657, and Isaac, born about 1659. "The refugees," Baird writes, "found much, doubtless, to bind them to the country of their adoption," where they were "encouraged in the free exercise of their religion." Moreover, he notes: "Openings for employment, if not enrichment in trade, were afforded in the prosperous city." Nevertheless, Baird tells us, these inducements to remain in Mannheim were not enough. "Influenced," he conjectures, "by a feeling of insecurity in a country lying upon the border of France, and liable to foreign invasion at any moment," Louis Du Bois "and certain of his fellow-refugees determined to remove to the New World." The first to make the journey to North America were Du Bois' father-in-law, Mathése Blanchan and his wife Madeline Jorisse, along with their three youngest children, and Du Bois' brother-in-law Antoine Crispel, who had married Maria, Catharine Blanchan's sister. On April 27, 1660 they sailed, probably from Amsterdam, aboard the Dutch West India Company vessel De Vergulde Otter (the "Gilded Otter"). They arrived at New Amsterdam (the present-day city of New York) in June, the voyage having lasted about six weeks. On the passenger manifest, both Blanchan's and Crispel's occupation is given as "agriculturist," i.e., farmer. Not counting Capt. Cornelius Reyersz Vander Beets and his crew, the tiny vessel carried one-hundred-and-eleven persons including a contingent of fifteen Dutch soldiers, one of whom was married and had two children, and ninety-three immigrants, most of whom were Dutch or Huguenot families. Two of the single passengers were Swedish. Although they are not included on the passenger list, which is apparently incomplete, it is believed that Louis Du Bois and his wife and two sons probably followed aboard the ship St. Jan Baptist, arriving at New Amsterdam on August 6, 1661. Here is how Henri and Barbara Van Der Zee, two modern-day authors, have described the arrival of an immigrant vessel in the harbor of New Amsterdam at about this time:

"The colonists of the 1650s and 1660s," the Van Der Zees have added, "must have been astounded by the overwhelmingly Dutch character of the town that had grown up there in thirty-five years." One contemporary visitor wrote" Most of the houses are built in the old way, with the gable end toward the street; the gable end of brick and all the other wall of planks…The streetdoors are generally in the middle of the houses and on both sides are seats, on which during fair weather, the people spent almost the whole day."

The Blanchan and Crispel families apparently did not remain long in New Amsterdam, however. By December 7, 1660, they were in the village of Esopus, "a small settlement of about eighty farmers halfway between New Amsterdam and Beverwyck," far up the Hudson River, where Dominie Blom, minister to the Dutch Reformed Church at that place, noted "their presence at his first celebration of the Lord's Supper." Not surprisingly, Louis and Catharine Du Bois and their two sons also settled in Esopus, following their landing in the New Netherlands a few months later. The original Esopus community, which was apparently nothing more than a collection of neighboring farms, was founded in 1652 by an Englishman named Thomas Chambers. Between that time and the arrival of our Walloon ancestors, the settlement had been raided several times by Indians. In 1658, upon the advice of Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant, the settlers, "sixty or seventy in number," built a new town that was fortified against Indian attacks. Unfortunately, this did not deter the Indians. "Another outbreak of Indian ferocity," writes Baird, "stimulated by the white man's "fire-water and provoked by the brutality of some of the Dutch themselves - occurred in the following year, when a band of several hundred Indian warriors invested the little town for three weeks." Fortunately, a few months before the Blanchan, Crispel, and Du Bois families arrived, Governor Stuyvesant had managed to make peace and put an end to the "Great Esopus War, which," Baird relates, "for many months past, had convulsed all the settlements, from Long Island to Fort Orange, with fear." In 1661, the village of Esopus was re-named Wiltwyck and it is Baird, once again, to whom we turn for a description of what the place must have looked like to our recently-arrived ancestors:

Baird also notes that around this time, yet another fortified town was built in the area. At first the settlers simply called it "Nieuw Dorp" ("the New Village"). Later, they renamed it Hurley. It was here, not long after their arrival at Wiltwyck, that Louis Du Bois, his father-in-law, Mathése Blanchan, and his brother-in-law Antoine Crispel moved their families. Unfortunately, the peace that Peter Stuyvesant had earlier negotiated with the Indians of the Esopus region was not long-lasting. The Indians resented Stuyvesant for sending some Indian prisoners to the Dutch island of Curacao, in the Caribbean. "An additional grievance," apparently, was the settlers building the "New Village" on land that the Indians still claimed. Again we turn to Baird, to tell us what happened at Hurley and Wiltwyck, in the late spring and summer of 1663: Underrating either the courage or the strength of their wild neighbors, the settlers took no precautions against attack, but on the contrary, with strange infatuation, sold to them freely the rum that took away their reason and intensified their worst passions. The time came for an uprising. Stuyvesant had sent word to the Indian chiefs, through the magistrate of Wiltwyck, that he would shortly visit them, to make them presents, and to renew the peace concluded the year before. The message was received with professions of friendliness,. Two days after, about noon, on the seventh of June, a concerted attack was made by parties of Indians upon both the settlements. The destruction of the "New Village" was complete. Every dwelling was burned. The greater number of the adult inhabitants had gone forth that day as usual to their field work upon the outlying farms, leaving some of the women, with the little children, at home. Three of the men, who had doubtless returned to protect them, were killed; and eight women, with twenty-six children, were taken prisoners. Among these were the families of our Walloons: the wife and three children of Louis Du Bois, the two children of Matthew Blanchan, and Anthony Crispel's wife and child. The rest of the people, those at work in the fields, and those who could escape from the village, fled to the neighboring woods, and in the course of the afternoon made their way to Wiltwyck, or to the redoubt at the mouth of Esopus creek. Baird also tells us that the Indians were less successful in their attack on Wiltwyck, although they managed to burn twelve houses and take several more women and children into captivity, for a total of forty-five from both towns. Seven members of the court at Wiltwyck, in a letter to the Council of New Netherland, provided a more detailed account of the attack on their town in their official report, dated June 20, 1663. A portion of the report reads:

A small number of male villagers, some armed, some not, the report added, had managed to come running and put the Indians "to flight." "After these few men had been collected against the Barbarians," the burghers continued, "by degrees the others arrived, who as it has been stated, were abroad at their field labors, and we found ourselves when mustered in the evening, including those from the new village, who took refuge amongst us, in number 69 efficient men, both qualified and unqualified." Their first task, the report revealed, was to immediately replace "the burnt palisades…by new ones." That night, "the people [were] distributed…along the bastions and curtains to keep watch." A month passed before Governor Stuyvesant was able to gather and send a force of English and Dutch soldiers, under the command of Captain Martin Kregier, "for the defense of Wiltwyck, and for the rescue of the prisoners in the hands of the Esopus Indians." During that time, the people of the two settlements rebuilt their fortifications and buried their dead, twenty-four in all. It was also during this period that one of the captured women, Rachel de la Montagne, managed to escape "and was ready to conduct the rescuing party to the Indian fort, thirty miles to the south-west of Wiltwyck, wither the prisoners had been conveyed." On July 27, 1663, Kregier and his men set out. "Tradition," says Baird, tells us that Louis Du Bois "was one of the foremost members of the rescuing party." Unfortunately, by the time they reached the spot where the captives had first been taken, "the Indians had retreated…to a more distant fastness in the Shawungunk mountains. The soldiers, writes Baird, "pursued them, but without success, and after setting fire to the fort, and destroying large quantities of corn which they found stored away in pits, or growing in the fields, the party returned to Wiltwyck." Yet another month passed before some friendly Indians told the soldiers about the location of a new fort the Esopus Indians had built. Writes Baird:

Another version of the rescue credits Catharine Du Bois, Louis' wife, with being the prisoner who sang psalms:

This story, "which is dear to the Huguenot heart of New Paltz (a town that Louis Du Bois later helped to found)," writes Le Fevre, also includes "Louis Du Bois himself killing with his sword an Indian who was in advance of the rest before the alarm could be raised." The death of the Indian, "no doubt a scout…[who] had fallen asleep," it is said, "prevented the news of the approach of the white men being given to their savage foes." The intrepid Walloon is said to have also encountered an Indian woman named Basha, "who had gone to the spring a short distance north of the fort for water." When she attempted to alarm the warriors, "Louis Du Bois shot her with his gun and she fell in the spring, which still bears her name." As Le Fevre points out, Captain Kregier's report contained none of these details. "However," he writes, "we shall not give up the tradition as it contains nothing irreconcilable with the report…which deals mainly with the fighting done by his soldiers, while tradition would dwell more upon the condition of the captives." For the record, here is Captain Martin Kregier's account of the rescue, dated September 5, 1663:

Kregier reported that he and his men afterward cut down the Indian's maize, destroyed any weapons they found, and burned the fort. Before returning to Wiltwyck, they also took a great deal of booty, including deerskins, gun powder, and wampum belts. Although the story about Catharine Du Bois singing psalms prior to being burnt alive at the stake by her captors is a colorful one, at least one historian, E. M. Ruttenber, has given it little credence. His reasons are as follows:

Although Ruttenber himself made an error - the women and children were captured on June 7, not June 19 - this writer believes he is probably correct in his belief that the tradition is without any basis in fact, or that if it is not a complete fabrication, it may be embellishment. Perhaps the women did sing psalms to comfort themselves while in captivity. Baird's account also includes an error: Sarah Du Bois, supposedly taken captive with her mother, was not born until 1664, the year following this incident. We also know, from Kregier's account, that only three Du Bois children were captured. These would have been six-year-old Abraham, four-year-old Isaac, and Jacob, nearly two years of age, the first member of his family born in America. "These troubles over," Baird tells us, "the settlement enjoyed security from savage molestation." This was due in part, he tells us, to the near extermination of the Esopus tribe. This permitted the settlers to "extend their plantations further into the rich lands that were now without an owner." We also learn from Baird and others that in 1677, Louis Du Bois, "with several associates, removed from Wiltwyck to a spot they had discovered during their pursuit of the Indians." It was here, "in the beautiful Wallkill valley," that they "built their homes, near the base of the Shawungunk mountains." In honor of their former home on the Rhine, "and the days of their exile in Mannheim," they called the new settlement "le nouveau Palatinat" or "New Platz," a town that still exists to this day. We also know that the original deed to this land, granted by Governor Andros, is preserved at New Paltz. On March 27, 1694, nearly thirty-four years after coming to America and making his home in the Hudson River Valley of New York, Louis Du Bois wrote a will in which he named as heirs his wife Catrina (Catharine), sons Abraham, Jacob, David, Solomon, Louys, and Matthew, the children of his deceased son Isaac, and his daughter Sarah, who in 1682 had married Jooste Jans Van Meteren (who as small boy had been carried into captivity by the Indians, along with his future wife). A year or two later, he revoked the earlier will, making a different disposition of his estate. The will mentions a farm at Hurley and a lot in Kings[ton?], and land in New Paltz. Sometime after this, he died. The will was proved in court on March 26, 1696 and on July 16, 1697, Louis' widow, Catrina (Catharine) was sworn in as executrix. We do not know when she died. In the Huguenot church on Staten Island, an inscription in a memorial alcove mentions Louis Du Bois. It reads: NEW PALTZ

This website copyright © 1996-2016 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |