|

The Haycraft Family

The Haycraft Family in London |

James Haycraft, Jr. |

Samuel Haycraft, Sr.

(1752-1823)

By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D.

Samuel Haycraft, Sr., born on November 19, 1752,1 was the middle son of James Haycraft, Jr., a London chimney sweep "transported" in 1744 to Virginia, where he was sold into seven years indentured servitude following his conviction on a charge of burglary (see James Haycraft, Jr.). The name of Samuel's mother is unknown.

Samuel had three siblings: A sister named Catherine who died in infancy and two brothers: James Haycraft III (known in America as James Jr.), born in 1750; and Joshua--born in 1754. Their childhood home was Frederick County, Virginia, where their father is known to have resided in 1760.2

Samuel's mother and father died around 1762, when he was nine or ten years old. "Consequently," Samuel Jr. later wrote, "the children learned nothing about their ancestors beyond the vague impressions formed in infancy." The parents' place of burial has likewise been lost to history. For reasons that can only be guessed, John Neville, a wealthy Virginia planter, took the boys into his care and according to all accounts, "Samuel Haycraft [and presumably also his brothers] received a good common school education, and remained with Col. Nevill [sic] until he was of age, when, with a letter of recommendation, he started out to shift for himself in the world."3

In 1773, when Samuel Haycraft reached his majority, Frederick County, which is located in northwestern Virginia, was situated on the edge of what was then a raw frontier. Even today this area-the Shenandoah River Valley, lies in the heart of some of the most scenic country in North America. On the north it is bounded by the Potomac River, on the east by the lush, forest-covered Blue Ridge Mountains, and on the west by the North Ridge Mountains, also called the "Devil's Backbone." The Great Wagon Road, linking the port of Philadelphia with the colonial "backcountry" as far as South Carolina, once ran through the heart of Frederick County. (Today, it is Interstate Highway 81.) From the early eighteenth century right up to the time the American Revolution began in 1775, thousands of immigrants from England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Germany passed through the Shenandoah River Valley, following the Great Wagon Road, which linked the port of Philadelphia with the "backcountry" of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North and South Carolina. When these travelers reached Frederick County, some liked what they saw and stayed. Others moved on.

One man who liked Frederick County very much was Lord Fairfax, an English aristocrat who owned thousands of acres of land in Northern Virginia and was the only English peer to make his home in America. In 1752, the very year in which Samuel Haycraft was born, Lord Fairfax went to live on a country estate called Greenway Court in Frederick County, where he remained for the rest of his very long life. (He died in 1781 at the age of eighty-eight.) Another well-known gentleman with close ties to Frederick County was future president George Washington, who first visited the Shenandoah Valley in 1748, while on a surveying expedition for Lord Fairfax. Washington ended up staying until 1765. During the very same time that Samuel Haycraft was growing up in that area, Washington maintained a surveying office in Winchester, the seat of Frederick County, and in 1758 and 1761, he was elected to represent the people of that district in Virginia's colonial legislature-the House of Burgesses. One of those people, of course, was Samuel Haycraft. One man who liked Frederick County very much was Lord Fairfax, an English aristocrat who owned thousands of acres of land in Northern Virginia and was the only English peer to make his home in America. In 1752, the very year in which Samuel Haycraft was born, Lord Fairfax went to live on a country estate called Greenway Court in Frederick County, where he remained for the rest of his very long life. (He died in 1781 at the age of eighty-eight.) Another well-known gentleman with close ties to Frederick County was future president George Washington, who first visited the Shenandoah Valley in 1748, while on a surveying expedition for Lord Fairfax. Washington ended up staying until 1765. During the very same time that Samuel Haycraft was growing up in that area, Washington maintained a surveying office in Winchester, the seat of Frederick County, and in 1758 and 1761, he was elected to represent the people of that district in Virginia's colonial legislature-the House of Burgesses. One of those people, of course, was Samuel Haycraft.

Seventeen years before he reached adulthood-when Samuel Haycraft was not yet three years old, Robert Dinwiddie, the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, sent George Washington, at the head of a small band of colonial troops, to build a road to the Monongahela River, near the spot where the French had constructed a stronghold called Fort Duquesne, located at the juncture of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers (on the site of present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Dinwiddie was worried about the growing French presence in the Ohio River Valley, which was then also claimed by the Colony of Virginia. Dinwiddie had also tried, and failed, to build a fort in the disputed region. At the Battle of Fort Necessity, in what is now western Pennsylvania, Washington was defeated in a skirmish with the French and their Indian allies. It was the future president's first military experience. The following year (1755), Gen. William Braddock, commander of His Majesty's British forces in North America, led an army of Regulars and Virginia Colonial Militia (which included Colonel Washington), on a march from Winchester, the seat of Frederick County, into the Ohio River country, in an unsuccessful attempt to dislodge the French from Fort Duquesne. The Battle of the Monongahela, which cost Braddock his life, marked the beginning of a conflict that the Americans called the French and Indian War (known in Europe as the "Seven Years War" since it did not officially begin until 1756). Of course if Samuel Haycraft had caught a glimpse of Washington or Braddock and their men at this time, it is doubtful he would have remembered it later, considering that he was two or three years old at the time. Seventeen years before he reached adulthood-when Samuel Haycraft was not yet three years old, Robert Dinwiddie, the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, sent George Washington, at the head of a small band of colonial troops, to build a road to the Monongahela River, near the spot where the French had constructed a stronghold called Fort Duquesne, located at the juncture of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers (on the site of present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Dinwiddie was worried about the growing French presence in the Ohio River Valley, which was then also claimed by the Colony of Virginia. Dinwiddie had also tried, and failed, to build a fort in the disputed region. At the Battle of Fort Necessity, in what is now western Pennsylvania, Washington was defeated in a skirmish with the French and their Indian allies. It was the future president's first military experience. The following year (1755), Gen. William Braddock, commander of His Majesty's British forces in North America, led an army of Regulars and Virginia Colonial Militia (which included Colonel Washington), on a march from Winchester, the seat of Frederick County, into the Ohio River country, in an unsuccessful attempt to dislodge the French from Fort Duquesne. The Battle of the Monongahela, which cost Braddock his life, marked the beginning of a conflict that the Americans called the French and Indian War (known in Europe as the "Seven Years War" since it did not officially begin until 1756). Of course if Samuel Haycraft had caught a glimpse of Washington or Braddock and their men at this time, it is doubtful he would have remembered it later, considering that he was two or three years old at the time.

By the time that Samuel Haycraft came of age the French had been decisively defeated in battle at Montreal, Quebec, and other places, including Fort Duquesne. When a treaty ending the war was negotiated in Paris in 1763, King Louis XV ceded Canada and all the land west of the Appalachian Mountains as far as the Mississippi River to the British. In a separate treaty, the Spanish received another large tract called Louisiana, leaving the French with no possessions whatever on the continent of North America.

Although the French no longer presented an obstacle to colonial expansion in the west, in 1773 the Indians were still troublesome (although it could also be said that from the Indians' perspective, it was the white people who were troublesome), attacking colonists who were then exploring or moving into the northern parts of present-day West Virginia and Kentucky, not far from the place where Samuel Haycraft had grown up. On 09 June 1774, the Virginia Gazette reported the Indians' intention to prosecute a full-fledged war against the colonists:

An express arrived in Town [Williamsburg] last night from Pittsburg, with Letters to his Excellency the Governour from Captain Connelly, Commandant at that Place; giving an Account that the Shawanese [Shawnee] Indians have openly declared their Intention of going to War with the white People, to revenge the Loss of some of their Nation who have been killed; that they had scalped one of the Traders, and detained all the rest who were in their Towns; that it was expected the Cherokees would join them, as they had sent a [wampum] Belt last Fall to the Northern Nations to strike the white People, which had been received by the Shawanese and Waabath [Wabash] Indians; that the Six Nations postponed their Answer till this Spring; and that there is soon to be a grand Council in the lower Shawanese Town, where about seventy Cherokees and a Number of other Indians are to attend, on the Subject of going to War with the English-Sundry Parties are now gone out, by Order of Captain Connelly, for the protection of the Inhabitants, and are to assemble at the Mouth of Whaling Creek, in Order, if it is judged practicable, to go against the upper Shawanese Town.-The Delawares, who profess to be our Friends, informed Captain Connelly that a Party of Shawanese were now gone against the Settlement; and it is imagined that they will fall upon Green Brier-All the Country about Pittsburg is in a very ruinous and discredited Situation, the Inhabitants having chiefly fled, and forted themselves as low as Old Town on Potowmack [Potomac] River.4

Hard on the heels of this news and reports of actual Indian attacks in July, Virginia's governor, Lord Dunmore (see picture, left), called out the militia. Among the many area settlers who answered the call to arms was twenty-one year old Samuel Haycraft, who enlisted as a private in Capt. William McMachen's company, a body of men that consisted of three officers (a captain, a lieutenant, and an ensign), three non-commissioned officers (all sergeants), and thirty-two privates. One of the sergants was reportedly named John Haycroft (but this is probably a mistake on the part of the person who transcribed the original records, more likely this is either James or Joshua, not John). Another one of our ancestors, Thomas Gilliland, joined Capt. Michael Cresap's company as a private. Both Haycraft and Gilliland were on the pay roll at Pittsburgh (Fort Pitt).5 Hard on the heels of this news and reports of actual Indian attacks in July, Virginia's governor, Lord Dunmore (see picture, left), called out the militia. Among the many area settlers who answered the call to arms was twenty-one year old Samuel Haycraft, who enlisted as a private in Capt. William McMachen's company, a body of men that consisted of three officers (a captain, a lieutenant, and an ensign), three non-commissioned officers (all sergeants), and thirty-two privates. One of the sergants was reportedly named John Haycroft (but this is probably a mistake on the part of the person who transcribed the original records, more likely this is either James or Joshua, not John). Another one of our ancestors, Thomas Gilliland, joined Capt. Michael Cresap's company as a private. Both Haycraft and Gilliland were on the pay roll at Pittsburgh (Fort Pitt).5

The only large-scale encounter of this brief conflict (it was over in a matter of months), which is remembered as "Lord Dunmore's War," was a victory for the Virginia colonial militia. Known as the Battle of Kanawha or Point Pleasant, this clash between colonial militia and Shawnee and Mingo Indians led by a chief called Cornstalk took place in what is now the state of West Virginia on October 10, 1774. Unfortunately, owing to incomplete records, it is difficult to ascertain the extent of Samuel Haycraft's participation in this war. It does not appear, however, that he took part in its most decisive battle.

Precisely what Samuel Haycraft was doing between the time he was released from John Neville's guardianship in 1773 and the outbreak of the American Revolution, apart from his brief service in the Virginia colonial militia during Dunmore's War, is equally difficult to ascertain. He may have worked as a laborer for some farmer or plantation owner, or perhaps he was apprenticed to learn a trade. Unfortunately, we can only speculate and one guess is as good as another.

One thing is certain: On April 19, 1775 the first shots of the American Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. Shortly afterwards, the Continental Congress, to which George Washington was a delegate, convened in Philadelphia and among other things formed a Continental Army with Washington as its leader. The various colonies, including Virginia, also called for men to come to the aid of the Patriot cause and "in the latter part of the winter 1775 or the fore part of the year 1776," Samuel Haycraft once more offered his services, enlisting this time for a term of 2 years and six months as a private in Capt. James Hook's company, 13th Virginia Regiment, under the command of Col. John Gibson.6

Samuel Haycraft's Revolutionary War pension file papers, combined with muster rolls that have survived to the present day, reveal that although some companies of the 13th Virginia took part in the battles at Brandywine and German town (and also suffered through the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge), he was stationed "on the Frontier,"7 where for most of the young soldier's term of service Hook's company formed part of the garrison at Fort Pitt, where today only a stone and brick blockhouse, built in 1764, still stands to remind the citizens of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania of the origins of their city.

Fort Pitt, named for British Prime Minister William Pitt, lay at the tip of a triangular point of land, where the waters of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers flow together to create the Ohio River. It was here, at the so-called "Forks of the Ohio," in 1753, that the French first built a wooden stockade called Fort Duquesne, to bolster their claim to the Ohio River country. Five years later, during the French and Indian War, the French burned Fort Duquesne and then abandoned the site upon the approach of a superior British force. Between 1759 and 1761, at a cost of about £60,000, British soldiers constructed the solid five-pointed, star-shaped fort that Samuel Haycraft came to know well during the Revolutionary War after it fell into the hands of the State of Virginia. It is quite possible however, and even likely, that Samuel actually first saw the fort during his brief service in Lord Dunmore's War in 1774. In any event, here is a description of it:

The earth around the proposed work was dug and thrown up so as to enclose the selected position with a rampart of earth. On the two sides facing the country, this rampart was supported by what military men call a revetment,-a brick work, nearly perpendicular, supporting the rampart on the outside, and thus preventing an obstacle to the enemy not easily overcome. On the other three sides, the earth in the rampart had no support, and of course, it presented a more inclined surface to the enemy-one which could readily be ascended. To remedy, in some degree, this defect in the work, a line of pickets was fixed on the outside of the foot of the slope of the rampart. Around the whole work was a wide ditch which would, of course, be filled with water when the river was at a moderate stage.8

In 1772, three years prior to the start of the American Revolution, the British army abandoned Fort Pitt. The following year, "it was re-occupied and repaired by Dr. John Connelly, under orders from Lord Dunmore, Governor of Virginia."9 In 1774 the governor used it as a staging point for an attack on the Indians during the war that bears his name. (During that time, the governor's name was also temporarily attached to the Fort.) Interestingly, it was Samuel's former guardian, John Neville, at the time a captain in the Virginia Militia, who in August 1775 led approximately "one hundred armed men" from Winchester to Fort Pitt to take permanent possession of the deserted fort for the colony of Virginia, which it claimed was located within the boundaries of Augusta County. This action reportedly "created quite a considerable excitement" among the leaders of the colony of Pennsylvania, which also claimed the territory on which Fort Pitt was located.10 Neville, who was afterward commissioned a general in the Continental Army, also served on a committee for the district in which the fort was situated, the purpose of which was to prepare for defense and if possible, to make peace with the Indians of the region, which was done in 1776 when Neville met at Fort Pitt with a chief named Kiashuta and several other chiefs, promising that the Americans would not "march an army through" Indian land "unless we hear of a British army coming this course; in such case we must make all haste to march and endeavor to stop them." Jacob Van Meter, Samuel Haycraft's future father-in-law (and another one of our ancestors), who then resided near Garrard's Fort in what is now Greene County, Pennsylvania, also served on this committee.11

As the Revolutionary War progressed, "Fort Pitt seems to have risen in importance in the estimation of Congress, and demanded a more imposing force for its defence than the command of Major Neville." Consequently, General Lachlan McIntosh, with portions of the 8th Regiment of Pennsylvania and 13th of Virginia, were ordered there,"12 which brings us back to Samuel Haycraft.

Somehow, during the time he was helping to guard the frontier at Fort Pitt, Samuel Haycraft happened to meet eighteen-year-old Margaret Van Meter (also spelled Van Metre, Vanmeter, etc.), daughter of a former Frederick County, Virginia colonist named Jacob Van Meter, who in the late 1760s or early 1770s had taken up residence in what was then called the "Ten Mile Country," on land that was then being claimed by both Virginia and Pennsylvania. Perhaps they first saw one another when Margaret, also known as "Peggy," accompanied her father to Fort Pitt on business of some sort. In any event, the two young people met (Samuel was then only twenty-six), fell in love, and on 9 September 1778 they were married at Fort Pitt "by a Baptist Preacher by the name of John Corbly," with Samuel reportedly wearing his colonial militia uniform. Afterward, Margaret later testified, she and Samuel lived together at Pittsburg-the frontier settlement established in 1760 outside the walls of the fort-until her husband was discharged upon the expiration of his term of service, on 2 August 177913 (which means he probably enlisted in February 1776, which is close to the time he later remembered).

Later in life, when Samuel Haycraft applied for a federal pension based on his Revolutionary War service, certain individuals signed affidavits attesting to it. One was his brother-in-law Isaac Van Meter, who remembered that Samuel had also been stationed, for several months after his marriage, at a log stockade called Fort Laurens, located on the Tuscarawas River in what is now the state of Ohio. Named for Henry Laurens of South Carolina, who was then President of the Continental Congress, Fort Laurens was built in 1778 by Gen. Lachlan McIntosh, to serve as a "stepping stone" for an attack on the British garrison at Fort Detroit, in present-day Michigan.14 Van Meter also recalled that his brother-in-law frequently spoke "of the hunger and hardships he suffered at that post [Fort Laurens] and that he also complained that he "never had received his arrears of pay for his service and clothing and back rations." George Bruce, a fellow veteran, who likewise signed an affidavit on Samuel's behalf, corroborated Van Meter's testimony, recalling that "in the later part of the year 1778 and part of 1779" Samuel Haycraft had been "stationed on the Tuskaraway [sic] River at Fort Laurance [sic], in a light infantry company led by Capt. Thomas More, and that during that time, the soldiers had been "reduced almost the whole of the winter on half allowance of flour and meat." Bruce also remarked that "for a considerable time" the garrison had been "surrounded by a large company of Indians who prevented us from getting a supply of provisions."15

The story of Fort Laurens, the only American fort to be built in the Ohio country during the Revolution, is well documented. Throughout the war, the British encouraged several tribes in what is the state of Ohio to attack colonial settlements. In consequence of this situation, in 1778 General McIntosh planned a "formidable incursion into the Indian country" in order to "destroy their towns and crops." Before doing so, he had a "a regular stockaded work, with four bastions and defended by six pieces of cannon" constructed at the confluence of the Ohio and Beaver rivers (in what is now the town of Beaver, Pennsylvania), about thirty-four miles north of Fort Pitt. The new fort was named Fort McIntosh.16

In September 1778, before marching into Indian country, McIntosh took the precaution of meeting at Fort Pitt with the Delawares, who were a friendly tribe, to "obtain their consent to the passing of troops through their territory." Then, in October, "Gen. McIntosh assembled one thousand men, at the newly erected fort, at the mouth of [the] Beaver, and commenced this expedition," which unfortunately, as one observer has written, "seems to have been unproductive of any good effect."17

The season was so far advanced that the army only proceeded about seventy miles west of Fort McIntosh and halted on the west bank of the Tuskarawas river, a little below the mouth of Sandy creek. Here they built a fort on an elevated piece of ground and named it Fort Laurens. Colonel John Gibson was left in the fort with one hundred and fifty men, and the army returned to Fort Pitt.18

One of these one hundred and fifty men (another source says there were one hundred and eighty) was Samuel Haycraft, who also almost certainly took part in the construction of Fort Laurens, which was recollected many years later by John Cuppy, another veteran of the expedition:

Where Fort Laurens was built, [there] was no timber, on a high bank, and a barren back for half a mile or more; and the men had to carry in the timber, four or five to a stick. Made mostly of large, hard-wood timber, split, some six inches thick, bullet proof, planted in trenches three feet deep, solidly packed around, and extending fifteen feet above ground…the fort, which was on the west bank of the Tuscarawas, enclosed about an acre of ground and was the longest on the river. No pickets along the river bank, no high overlooking ground either near Fort McIntosh or Laurens. The gate was on the west side of the fort, no spring; relied upon the river for supply of water. There was one block-house, about 20 feet square, which was directly to the right of the gate, and next to it, and formed a part of the outside in place of picketing: the block-house, about six feet above the ground, the block-house was made a foot wider on the wall side, and made to over-jut, so if Indians came up, the garrison could shoot down through this open jut directly upon an enemy below; and the floor of puncheons on a level with the over-jut; and the timbers built up some eight feet, so as to completely protect those within from the enemy without, and port-holes all around about five feet from the floor, and some two or three feet apart, through to which for the garrison to fire in case of any attack, with a rude roof slanting one way and that within the fort…There were also 2 cabins built on each end of the fort, not quite together and in a line with the picketing, and helped to form the enclosure, and also had over-jutting, and with port-holes; but smaller than the block-house; and these were for shelter and provision.19

During the building of the fort, before Samuel Haycraft and some 150 of his comrades were left behind, the army was "encamped in the open ground in a semi-circle around Fort Laurens, some distance from the fort, but not so far back as the woods, in tents; every mess, composed of six or seven men, had a tent." All their baggage, Cuppy recalled "was packed on horses."20

Throughout this time, Cuppy likewise remembered, the "Indians were entirely peaceable" Not only were there were "no attacks from them," he said, but they "frequently visited the camp, and brought fine fat haunches of venison, bear meat and turkies, and presented [them] to the officers, who gave them some of their too beloved fire-water in return." The former soldier also recollected seeing the Indians, "both men and women," dancing "a hundred or more together, the taller taking the lead, and others falling into the circle, according to their height, the shortest bringing up the rear, and dancing around in the circle, to the rude music derived from beating upon a kettle by an old Indian, intermingled with occasional yells." Cuppy also remembered that Simon Girty, a Scots-Irish frontiersman that lived among the Indians, was present.21 Girty, who at the outset of the war was a friend to the Americans, afterward turned against them.

Informed of McIntosh's expedition, Gen. George Washington made it clear that he considered both Fort Laurens and Fort McIntosh to be "material posts." He was particularly anxious that Laurens, most probably due to its distance from any other fort, "be sufficiently garrisoned and…well supplied with provision that it may not be liable to fall through want in case of attack."22 Unfortunately, that is not what happened. In January 1779, when hostile Indians learned that the soldiers in the fort were not only few in number but also short on supplies, they decided to take advantage of the situation. Here is a description of the subsequent siege of Fort Laurens, according to one account:

The first hostile demonstration of the forest warriors was executed with equal cunning and success. The horses of the garrison were allowed to forage for themselves upon herbage, among the prairie grass in the immediate vicinity of the fort-wearing bells, that they might be the more easily found if straying too far. It happened one morning in January that the horses had all disappeared, but the bells were heard at no great distance. They had, in truth, been stolen by the Indians and conveyed away. The bells, however, were taken off, and used for another purpose. Availing themselves of the tall prairie grass, the Indians formed an ambuscade, at the farthest extremity of which they caused the bells to jingle as a decoy. The artifice was successful. Sixteen men were sent in pursuit of the straggling steeds, who fell into the snare. Fourteen were killed upon the spot and remaining two taken prisoners; of these latter, one of whom returned at the close of the war, and of the other nothing was ever heard.

Toward evening of he same day, the whole force of the Indians, painted, and in full costume of war, presented themselves in full view of the garrison, by marching in single files, though at a respectful distance, across the prairie. Their number, according to a count from one of the bastions, was eight hundred and forty-seven-altogether too great to be encountered in the field by so small a garrison. After this display of their strength, the Indians took a position upon an elevated piece of ground at no great distance from the fort, though on the opposite side of the river. In this situation they remained several weeks, in a state of armed neutrality than of active hostility. Some of them would frequently approach the fort sufficiently near to hold conversations with those upon the walls. They uniformly professed a desire for peace, but protested against the encroachments of the white people upon their lands-more especially was the erection of a fort so far within the territory claimed by them as exclusively their own, a cause of complaint-nay, of admitted exasperation. There was with the Americans in the fort, an aged friendly Indian named John Thompson, who seemed to be in equal favor with both parties, visiting the Indian encampment at pleasure, and coming and going as he chose. They informed Thompson that they deplored the continuance of hostilities, and finally sent word by him to Colonel Gibson, that they were desirous of peace, and if he would present them with a barrel of flour, they would send in their proposals the next day. The flour was sent, but the Indians, instead of fulfilling their part of the stipulation, withdrew, and entirely disappeared. They had, indeed, continued the siege as long as they could obtain subsistence, and raised it only because of the lack of supplies. Still, as the beleaguerment was begun in stratagem, so was it ended.23

Some accounts of this episode report that a small contingent of British soldiers under the command of Captain Henry Bird also took part in the siege of Fort Laurens. "However," states one source, "it would appear that he remained at Sandusky, directing the raids [against the Americans], and watching to prevent the anticipated American march against Detroit."24

Shortly after the apparent withdrawal of the Indians, Colonel Gibson, worried that his "provisions were…running short," sent "a detachment of fifteen men" led by "Colonel Clark, of the Pennsylvania line" to Fort McIntosh, as an escort for "the invalids of the garrison." The move turned out to be unwise because unknown to Gibson, "the Indians had left a strong party of observation lurking in the neighborhood of the fort."25 Consequently, "the escort had proceeded only two miles before it was fallen upon, and the whole number killed with the exception of four-one of whom, a captain, escaped back to the fort." Afterward, "the bodies of the slain were interred by the garrison, on the same day, with the honors of war". Soldiers were also "sent out to collect the remains of the fourteen who had first fallen by the ambuscade, and bury them." No doubt to their horror, the burial party discovered that wolves had been eating the flesh of the dead soldiers. After interring their fallen comrades, the men set traps "upon the new-made graves." The next morning, "some of those ravenous beasts were caught and shot."26

Afterward, as Samuel Haycraft seems to have remembered for the rest of his life, the "situation of the garrison" became "deplorable." "For two weeks the men had been reduced to half a pound of sour flour, and like quantity of offensive meat, per diem; and for a week longer they were compelled to subsist only upon raw hides, and such roots as they could find in the circumjacent woods and prairies."27 One man later recalled that near the end of four-week-long siege, the men "had to live on half a biscuit a day-then the last two days washed their moccasons [sic] and broiled them for food, and broiled strips of old dried hides." He also remembered that when two soldiers "stole out and killed a deer" and then "returned with it, it was devoured in a few minutes, some not waiting to cook it."28

Finally, General McIntosh "most opportunely arrived to their relief, with supplies and a reinforcement of seven hundred men." Unfortunately, due to "an untoward incident" that caused "the loss of a great portion of their fresh supplies," the soldiers "came near to being immediately reduced to short allowance again."29

These supplies were transported through the wilderness upon pack-horses. The garrison, overjoyed at the arrival of succors, on their approach to within about a hundred yards of the fort manned the parapets and fired a salute of musketry. But the horses must have been young in the service. Affrighted at the detonation of the guns, they began to rear and plunge, and broke from their guides. The example was contagious, and in a moment more, the whole cavalcade of pack-horses were bounding into the woods at full gallop, dashing their burdens to the ground and, and scattering them over many a rood in all directions-the greater portion of which could never be recovered. But there was yet enough of provisions saved to cause the mingling of evil with the good. Very incautiously, the officers dealt out two days' rations per man, the whole of which was devoured by the famishing soldiers, to the imminent hazard of the lives of all, and resulting in the severe sickness of many. Leaving the fort again, General M'Intosh assigned the command to Major Vernon, who remained upon the station several months. He, in turn, was left to endure the horrors of famine, until longer to endure was death; whereupon the fort was evacuated and the position abandoned-its occupation and maintenance, at the cost of great fatigue and suffering, and the expense of many lives, having been of not the least service to the country.30

During the siege of Fort Laurens, Col. Daniel Brodhead wrote to General Washington from Fort Pitt to inform him that General McIntosh "is unfortunate enough to be almost universally Hated by every man in this department, both Civil and Military." Adding that he did not think it was possible for McIntosh to "do any thing Salutary," Brodhead added: "There is not an Officer who does not appear to be exceedingly disgusted, and I am much deceived if they serve under his immediate Command another Campaign."31 Considering the suffering they had been made to endure and the loss of several of their comrades' lives for no apparent good reason, enlisted men like Samuel Haycraft almost certainly felt the same way. In light of this seemingly universal opinion and also because McIntosh had reportedly asked to be relieved of command, the Continental Congress passed a resolution on 20 February 1779 recalling him and permitting General Washington to appoint Brodhead as his replacement.

It is also not hard to imagine that upon Samuel Haycraft's return to Fort Pitt on April 7, 1779,32 his young wife greeted him with tears of joy and relief that he had survived an ordeal that had proved deadly to others.

There are three extant Revolutionary War muster rolls in the National Archives with Samuel Haycraft's name on them. The oldest is dated March 17, 1778, showing him present at Fort Pitt as a member of Captain Russell's company. The second, covering the months of April and May 1779, records his presence at Fort Pitt as a member of Captain Springer's company. The final roll showing him present at Fort Pitt as a member of Lt. Ephraim Ralph's company, in the newly designated 9th Virginia Regiment is for July, August, and September 1779. (Note: On 12 May 1779 the13th was reorganized as the 9th Virginia Regiment.) This third muster roll also shows, following what was hopefully a relatively uneventful four months his return from Fort Laurens, Samuel Haycraft was discharged upon the expiration of his term of service on 2 August 1779.33

Earlier, on 3 May 1779, Major (formerly Captain) Brodhead wrote to General Washington informing him that Fort Laurens was to be abandoned on 25 May and regarding a seemingly unrelated topic, he expressed concern about the "Great numbers of the inhabitants" of the region around Fort Pitt that were "daily moving down the Ohio to Kentucky and the Falls," which in the Major's opinion, was something that "greatly weakens the frontier."34

In spite of any misgivings entertained by Major Brodhead, Samuel Haycraft and his bride were not long in joining this exodus. In March 1779, Haycraft's father-in-law, Jacob Van Meter, along with several other members of the Goshen Baptist Church, of which Van Meter was a deacon, received letters of dismission from their church after first obtaining "recommendations from the County Court of Monongahela to pass [with their families] unmolested to the Falls of Ohio." The others included John Corbly, the minister who had performed Samuel and Peggy's marriage ceremony, Abraham Van Meter, Isaac Dye, John Eastwood, Abraham Holt, John Holt, and Robert Tyler.35

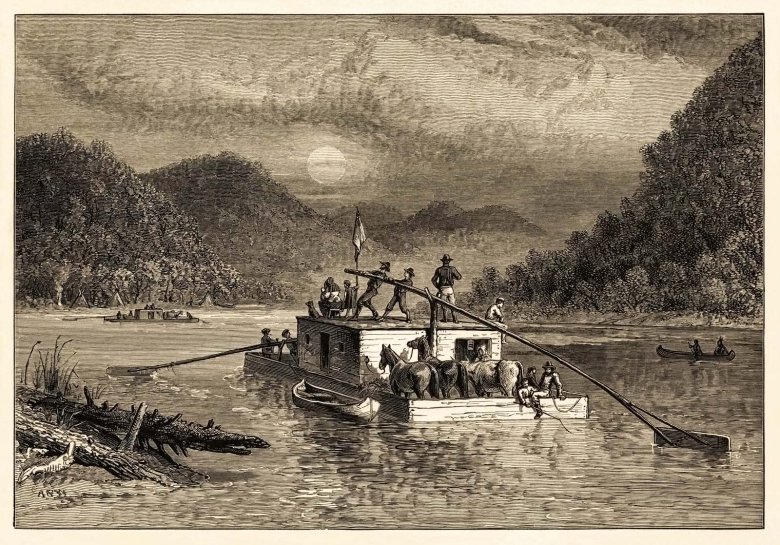

In 1779 Kentucky was a virgin territory that lay just to the west of the Appalachian Mountains. The now-legendary pioneer Daniel Boone had settled there only four years earlier, after passing through the famed Cumberland Gap. Unlike Boone however, the Van Meter family and their friends planned to enter Kentucky from the north by traveling down the Ohio River from Pittsburg.36

David McClure, author of Two Centuries in Elizabethtown, has described the Van Meter expedition's not-uneventful trip down the Ohio River to Kentucky:

Minutes of a Court held for Yohoghania County, Virginia March 23, 1779 (this prior to the date when that section was established as part of Pennsylvania) granted permission to pass unmolested to the Falls of the Ohio. On September 18, 1779, Jacob Van Meter and his family had been granted certificates of dismission by the Goshen Baptist Church. Soon twenty-seven house boats were, under the direction of Jacob Van Meter, Sr., floating down the Ohio, bringing the families and all their household goods, livestock and anything they could pile on the boats. All of the Van Meter children, with [the] exception of daughter Eleanor, accompanied their parents, together with their husbands and wives. One babe in arms was in the party, the little daughter of Lieutenant John Swan, Jr., and his wife, Elizabeth Van Meter. Swan was sitting on deck on one of the boats with his little girl in his arms when he was struck by an Indian arrow, fired from the river bank. His wife grabbed his gun and began helping the men ward off the attack. Another tragedy struck the party. Mary Van Meter's husband, David Henton, fell into the river while helping unload the boats and was drowned. Henton's death left his widow with two children, Hester Henton, born January 9, 1775, who would marry Walter Briscoe, and John C. Henton, born November 9, 1778, who would marry Catherine Keith.37

Another author, Howard L. Lecky, has also described the incident that resulted in the death of John Swan, Jr. It is included here because it provides us with a more detailed account than McClure's. Writes Lecky:

With members of his own and his wife's families, John Swan, Jr., with his wife and small children were floating down the Ohio River to take up land [in Kentucky], and when a short distance below Fort Pitt, while John Swan, Jr., was fast asleep on the flat boat with his young daughter in his arms, he was shot through the breast by an Indian on the shore. So fatal was the shot that those aboard were unaware of the incident until the child cried out: "Oh! Papa has been shot and warm blood is running over me." The party on board made ready to repel an attack and began a vigorous fire at the enemy on the shore, the newly-made widow of John Swan, Jr., loading guns for Joseph Hughes, brother-in-law of the dead man, until they drove off the raiders. The party then sadly proceeded to their destination.38

McClure goes on to report that others in the party were "Stephen Rawlings, father of Edward Rawlings, who had married Rebecca Van Meter, together with his family…So was Jacob Van Meter, son of Henry Van Meter, one time ensign in Clark's Illinois Regiment and later a captain of Jefferson County Militia." Two families of Negro slaves "belonging to the senior Van Meter" also made the trip. McClure notes that in Jake Van Meter's will there was a provision "that they were to be set free upon the death of his wife" after serving her during her lifetime "but if she lived until they were thirty years old, they were to be given their freedom."39

Another slave who traveled to Kentucky in this party was "General Braddock," (named for the famous British general killed in the French and Indian War) who belonged to Jake's son Abraham Van Meter. McClure reports that the slave had gained both his nickname and a degree of fame for killing nine Indians. Many years later, after his master was killed by Indians at Boone's Fort, "General Braddock" was "set free forever." He afterward married a woman named Becky Swan (apparently a slave or former slave belonging to the Swan family) and settled on a farm near Elizabethtown, Kentucky.40

Unfortunately, more than Indians troubled the Van Meter party on their journey to Kentucky. As it turned out, they had inadvertently chosen to travel during a period time of severe wintertime weather that was ever afterward known as "the Hard Winter of 1780." Seventy years later, one writer recalled its adverse effects on travelers:

The winter of 1779'80, was a marked era in the history of the West. It proved to be uncommonly severe, insomuch that it was distinguished as the Hard Winter. The rivers, creeks, and branches, were covered with ice of great thickness, where the water was sufficient; while the latter were generally converted into solid crystal. The snow, by repeated falls, increased to an unusual depth, and continued for an extraordinary length of time: so that men, and beasts, could with much difficulty travel; and suffered greatly in obtaining food, or died of want and the cold, combined.

Many families traveling to Kentucky, in this season, were overtaken in the wilderness, and their progress arrested by the severity of the weather. Compelled to encamp and abide the storm, the pains of both hunger and frost were inflicted on them, in many instances, in a most excruciating degree. For when their traveling stock of provisions was exhausted, as was soon the case with many, and some of these without a hunter or live stock; they were left without resource, but in begging at other camps. And even, where there were hunters, they found it extremely difficult to traverse the hills for game, or to find it when sought; while in a short time, the poor beasts, oppressed by cold and want of food, soon became lean, and even unfit for use, or unwholesome, if eaten. Such also became the case with the tame cattle of the emigrants-many of them died for want of nourishment, or were drowned by floods, as they happened to be on the hills where there was no cane, or on the bottoms which overflowed, on the breaking up of the ice. And it is a fact, that part of those dead carcasses became the sole food of some of the unfortunate and helpless travelers. Their arrival in Kentucky, when effected, offered them a supply of wholesome meant, but corn was scarce, and bread, at first obtained with difficulty, soon disappeared and could not be procured.

The very great number who had moved into the country, from the interior, in the year 1779, compared with the crop of that year, had nearly exhausted all that kind of supply before the end of the winter, and long before the next crop was even in the roasting-ear state, in which it was eaten as a substitute for bread, there being of that article none to be had, until the new crop became hard. And while the corn was growing to maturity, for use, wild meat, the game of the forest, was the only solid food of the multitude; and this, without bread, with milk and butter, was the daily diet of men, women and children, for some months. Delicate or robust, well or ill, rich or poor, black or white, one common fare supplied, and the same common fate attended all. The advance of the vernal season brought out the Indians, as usual; and danger of life and limb, was added, to whatever else was disagreeable, or embarrassing in the condition of the people.41

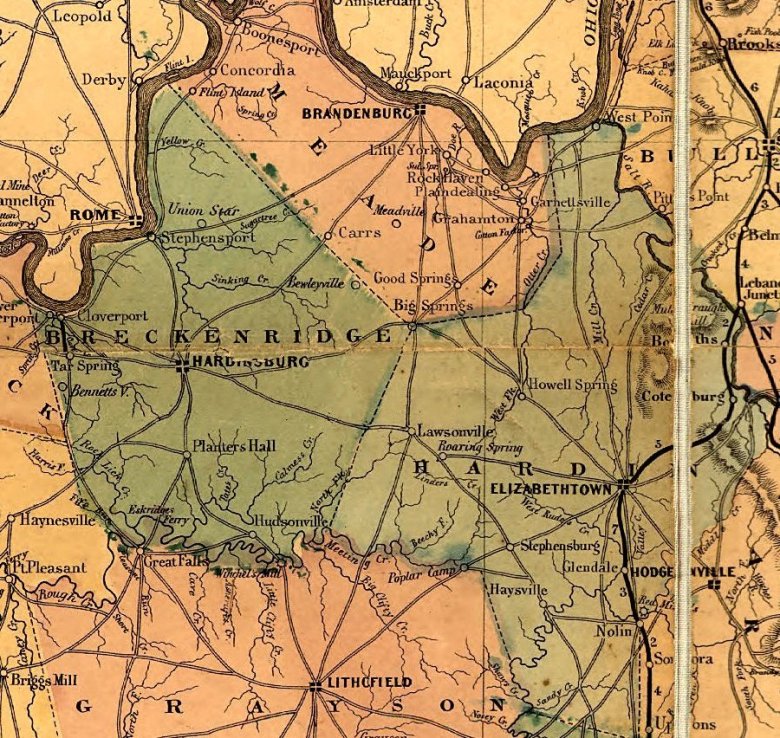

Despite these hardships, in the spring of 1780 the Van Meter party reached the Severns Valley, in what was then Jefferson County, Kentucky.42 Jefferson County records reveal that Jake Van Meter, Stephen Rawlings, and Edward Rawlings all bought land from John Severns, for whom the valley was named. To protect themselves from Indians, they immediately built wooden "forts" (probably log blockhouses). Van Meter's fort was located, according to one source, "near the big spring at the power house on Leitchfield road, for a long time the source of the Elizabethtown water supply."43

This map of Kentucky was made in the late 1700s, before Hardin County and Elizabethtown were established. Courtesy Library of Congress.

In his celebrated History of Elizabethtown Kentucky, which was first published as a series of late nineteenth century newspaper articles, Samuel Haycraft, Junior wrote that "Captain Thomas Helm, Colonel Andrew Hynes and Samuel Haycraft [Senior]" were also "early settlers" of the Severns Valley-a statement confirmed by land grant records on file in records of the Library of Virginia for Helm and Hynes (but curiously, not for his father). He added: "Each of these persons built forts with block houses. The forts were stockades, constructed of split timber-then deemed sufficient for defense against the Indian rifles. The sites were well-selected, each on elevated ground, commanding springs of never failing and excellent water."44 Employing language that was typical of the nineteenth century (most notably his use of the word "savages" as a name for the Indians), Samuel Junior went on to describe the living conditions that his parents and the other early settlers of the Severns Valley experienced:

The forts formed a triangle, equidistant a mile apart. Captain Helm's fort occupied the hill on which Governor Helm's residence now stands. Colonel Hynes' was on the elevation now occupied by J. H. Bryan, formerly by Ambrose Geoghegan, Sen., and for many years by John H. Geoghegan, Esq. Haycraft's fort was on the hill above the Cave spring, in which the flesh of many a deer, buffalo and bear were preserved for use, as salt in these days were not to be had. There were no other settlements at that time between the falls of the Ohio and Green river. Those forts were subject to frequent attacks by the Indians. The report of a gun at either of these forts was the signal by which the other forts were warned of danger and summoned to the aid of the besieged fortress, which was promptly responded to. Many were the inroads made by savages upon the infant settlements at that early period. Soon after a hardy set of adventurers came in and settled around the forts, consisting of the Millers, Vertreeses, Vanmeters, Harts, Shaws, Dyers, &c., who assisted in repelling the attacks of the Indians. Many deeds of daring valor were performed by those sturdy pioneers. It cost some blood. Henry Helm, son of old Capain Thomas Helm, was killed; also Dan Vertrees, the honored grandfather of Judge W. D. Vertrees, our fellow citizen.45

Samuel Junior also mentioned that in the early days of settlement, the stockades built by his father and others were called "stations" and described how they were built:

The manner of erecting these forts was to dig a trench with spades or hoes or such implements as they could command, then set in split timbers, reaching ten or twelve feet above the ground and having fixed around the proposed ground sufficiently large to contain some five, six or eight dwellings with a block house, as a kind of citadel with port holes. That was considered a sufficient defense against Indians armed with rifles or bows and arrows, but with a siege gun of the present day a well directed shot would level a hundred yards of these pristine fortifications. The mode of attack by the Indians was to try to storm the fort, or by lighted torches thrown upon the roofs of the buildings within to burn out the besieged, but they rarely succeeded in setting fire. If in small force the Indians would shield themselves behind trees and watch a whole day for some unwary pale-face to show himself above the fortification and pick him off. But this was a two-handed game, for it sometimes happened that the red skin in peeping from his tree got his brains blown out. It was very rare that the siege was continued after an Indian was killed, for those Indians were remarkable for carrying off the dead and wounded, even on field of battle. It was a war custom of the Indians never to take an open field fight, but always treed or lay low in the small cane or high grass, and this mode of fighting was more universally adopted by the old and experienced braves than by the young and untaught warriors. If by deploying the whites could get a raking fire upon the red man, they retreated hastily to more distant trees and renewed the fight, and if by force of circumstances they were compelled to me to a hand-to-hand fight they fought with the desperation of demons, using the scalping knife, war axe and war club.46

"The colony," continued Samuel Junior, "which came to Kentucky with my father, Samuel Haycraft, Sr., consisted of his wife, my mother, Jacob Vanmeter and wife, Jacob Vanmeter, Jr., Isaac and John Vanmeter, Rebecca Vanmeter, Susan Gerrard and her husband, John Gerrard, Rachel Vanmeter, Aisley Vanmeter, Elizabeth Vanmeter and Mary Hinton. All of them, with my mother, were sons, sons-in-law and daughters of Jacob Vanmeter, Sr. Hinton was drowned on the way in the Ohio river. There was also a family of slaves belonging to the elder Vanmeter. These all settled for a time in the valley."47

In 1777, Samuel Haycraft's younger brother, Joshua, had joined the Patriot cause as a private in Colonel Daniel Morgan's 11th Virginia Regiment (which was reorganized in 1779 as the 7th Virginia Regiment)--a unit consisting mostly of men from Frederick and surrounding counties. The 11th took part in the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. Curiously, although older brother James was also of military age, there seems to be no record of any military service on his part. In any event, sometime in the 1780s or early 1790s, after Samuel Haycraft and his family had settled in the Severns Valley of Kentucky, his brothers James and Joshua joined him there.48

Samuel Junior added that most of the early settlers "opened farms in the neighborhood" and that "the men and women married and propagated at a round rate, averaging about a dozen children, and they have so multiplied that their name is legion and are now scattered over nearly every State and Territory in the Union." His mother and father were certainly no exception; during a fifteen year period between 1782 and 1797 Samuel Haycraft, Sr. and his wife Peggy had the following named children: (Note: All indicated marriages occurred in Hardin County, Kentucky.)

- Nancy Haycraft, born 11 September 1782, married John Vertrees 02 January 1800.49

- John Neville Haycraft, born 30 March 1784, marriage to Nancy Melone recorded 05 October 1803.50

- Leticia Haycraft, born 15 December 178651 (no marriage record found)

- Amelia Haycraft, born 27 August 1788, married Jonathan Shepherd 12 April 1807.52

- Polly Haycraft, born 15 April 1790, married Jacob Chenowith 07 January 1808.53

- Elizabeth "Betsey" Haycraft, 16 March 1792, married Isaac Morrison 19 July 1812.54

- Rebecca Haycraft, born 15 April 1793, married Adkinson Shepherd April 1811.55

- Peggy Haycraft, 12 November 1794, married Thomas Williams 20 November 1817.56

- Samuel Haycraft, Jr., August 1795, married Sarah Brown Helm 29 October 1818.57

- Presley Neville Haycraft, 08 April 1797, married Elizabeth Kennedy 03 September 1818.58

After establishing farms, the settlers began next to form religious congregations. The very first in the area, a Baptist church organized on 17 June 1781 "under the shadow of a green sugar tree, near Haynes' station," consisted of eighteen people including Samuel Haycraft's Van Meter in-laws. "Elder William Taylor and Joseph Barnett, preachers, with Elder John Garrard, who was ordained first pastor" led the congregation. As it happened, Garrard "was only permitted to exercise the functions of his office for nine months." One day, the unlucky minister was hunting game with a party of friends when Indians ambushed them. Everyone except Garrard, "he being lame," escaped. "Whether he was slain outright, burnt at the stake, or lingered in captivity was never known, and like Moses the place of his sepulcher is not known."59

Samuel Haycraft, Jr., who wrote the above account, noted that he received his information about the early days of the Severns Valley Baptist Church from his uncle, Jacob Van Meter, Jr., who also told him:

They then had no house of worship. In the summertime they worshipped in the open air, in the winter time they met in the round log cabins with dirt floors, as there was no mills and plank to make a floor. A few who had aspired to be a little aristocratic split timber and made puncheon floors.

The men dressed as Indians; leather leggins and moccasins adorned their feet and legs. Hats made of splinters rolled in Buffalo wool and sewed together with deer sinews or buckskin whang; shirts of buckskin and hunting shirts of the same; some went the whole Indian costume and wore breech-clouts. The females wore a coarse cloth made of Buffalo wool, underwear of dressed doe skin, sun bonnets, something after the fashion of men's hats and the never-failing moccasin for the feet in winter, in summer time all went barefooted.

When they met for preaching or prayer, the men sat with their trusty rifles at their sides, and as they had to watch as well as pray, a faithful sentinel keeping a look out for the lurking Indian. But it so happened that their services were never seriously interrupted, except on one occasion. One of the watchers came to the door hole during a sermon and endeavored by signs and winks to apprise the people that something was wrong-not being exactly understood, a person within winked at the messenger, as much as to say, "Don't' interrupt us." But the case being urgent, the outside man exclaimed, "None of your winking an blinking-I tell you the Indians are about."

This was understood, the meeting was closed, and military defense organized."60

Samuel Haycraft, Jr. wrote too that as young man he often "heard old people talk with great fondness of old forting times as a green spot in their history-they loved to dwell upon the scenes of early trails and dangers, when men and women were all true hearted and no selfishness." He added:

No burthened field of corn; no waving fields of wheat came to the harvest; no potato crop burrowed the earth. The wild game that roamed the forest was the only dependence the first year; the rifle was indispensable. It was made common cause, food was obtained at the risk of life. The unsuccessful hunter lacked nothing. The man who brought down the buffalo, the deer or bear, divided out and all had plenty. When news reached a fort that Indians were around, all were upon the alert, the mean seeing that their weapons were in order, and the women…went to their neighbor, and inquired, "Have you plenty of meat? If you have not I have it." And immediately there was an equal division. The dried venison, called "jirk," was the bread; the fat, juicy bear the esculent, the bulky buffalo, the substantial; and the turkey the dessert; nobody had the dyspepsia and all had good teeth. But soon the brawny arm leveled the forest[,] fields were opened and a plenty of the substantials in life soon blessed their labors.61

In 1783, the Revolutionary War came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, in which Great Britain not only conceded defeat but also recognized the independence of the fledgling United States. No doubt Kentucky settlers such as Samuel Haycraft breathed a sigh of relief, confident now that their all their efforts to start a new life for themselves in the Trans-Appalachian West would not be undermined by any new laws or proclamations emanating from London.

It is certain however, that the native population of this region, most of who had sided with the British in the late conflict, were less than happy with the war's outcome. Soon, they knew, even more uninvited trespassers would come pouring over the mountains into the valleys of the west. The Indians knew too that these were people who saw the continent's original inhabitants as "savages" and impediments to progress. They were also a people who also firmly believed (although their was no actual evidence to support that belief) that a benevolent God had ordained them to overspread the continent of North America--a conviction that would later be termed "Manifest Destiny."

In 1792, a dozen years after Samuel Haycraft and his wife and in-laws first settled there, Kentucky was officially separated from Virginia, becoming the fifteenth state in the Union. The following spring Hardin County was formed from part of Jefferson County by an act of the state legislature and on 22 July 1793 "the first term of the county court was held at the house of Isaac Hynes." The following month, "Samuel Haycraft was appointed" by the court "to take in the lists of taxable property for Hardin County"-a job that took thirty-one days, for which he was afterward paid at a rate of six shillings per day (for a total of nine pounds and three shillings). At the same session, the court decreed that a poor house and jail would be built on land belonging to Andrew Hynes, "on that part of said land that adjoins Samuel Haycraft." The court likewise ordered roads to be laid off, from the courthouse to various points in the county. This was no easy job. One proposed road, Samuel Haycraft, Jr. wrote, was "seventy-five miles long" and went "through a trackless country."62

This map of Hardin County is part of a larger map of Kentucky, published in 1862. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Later this same year (1793), Samuel Haycraft's brother Joshua volunteered for forty days service in Company H of David Caldwell's Battalion of Kentucky Cavalry, which was raised to supplement the troops under command of Gen. "Mad Anthony" Wayne in the Ohio Country, where there had recently been skirmishes with Indians. Joshua's military service record shows that he enlisted on 06 October, was present for muster on 11 November at Fort Washington, about where the city of Cincinnati, Ohio stands today, and was mustered out on 14 November.63 There is no indication however, that he took part in any battles or skirmishes during this short span of time.

At the May 1795 term of the Hardin County court, "Samuel Haycraft, gentleman, produced a commission from Governor Isaac Shelby, appointing him sheriff of Hardin County, and was qualified and gave bond with John Vertrees, Stephen Rawlings, and John Paul, his securities." Edward Rawlings, a tall muscular young man, was appointed deputy sheriff.64

Between 1794 and1803 there was an inordinate amount of "hot blood" between the residents of the Severns Valley settlement of Elizabethtown, which had been laid out in 1793 on thirty acres of land belonging to Andrew Hynes, and the Nolin settlements (located in the southwestern section of Hardin County) as to which place would become the permanent county seat. This difference of opinion was due largely to the fact that Elizabethtown was "only ten miles from the upper end of the county, and one hundred and thirty miles from the lower end of the county, which was sparsely settled." During that period, and "particularly at the annual elections" there were reportedly no fewer than "fifty combats of fist and skull, there being no pistols, knives, brass knuck or slungshots used in those days."65

Although the Nolin settlers surely objected, they were outnumbered and in 1795, the first county court house was erected in the upper end of the county, in what is now Elizabethtown, on 14 August 1795.66

According to Samuel Haycraft, Jr., who was born that very same day, the building of the first Hardin County courthouse was a community affair, with every able-bodied male living in the vicinity taking part. Writing in 1869, here is how he described it:

Many hands made light work, so that on the 14th day of August, 1795, most glorious day, all was ready for the grand raising. Skids and hand-spikes and pushing dog-wood forks all ready, and forty strong hands on the ground with numerous women and children to behold the grand sight.

A little difficulty sprang up about the feeding of such a large force of healthy, hearty men, each of whom could lift three or four times as much weight, and each of them could eat nearly the tenth part of his weight avoirdupois.

My father's double log-house cabin was the only chance. The old house stood about seventy yards southeast of the fine dwelling house of T. H. Gunter, Esq. It was in the middle of what is now the railroad tract, and in this connection I will show what the women of the olden times could perform. My mother and eldest sister, with some younger ones, to hand things and bring water, go the dinner in the style of those halcyon days. Large loaves of bread from the clay oven, roast shoats, chickens, ducks, potatoes, roast beef with cabbage and beans, old-fashioned baked custard and pudding, and the indispensable pies, pickles, etc., etc.

Well, the dinner was set, all hands had their fill, the men back to their work, the table cleared off, the crumbs shook out to the dogs, the dishes, pewter spoons, knives, forks and pewter basins wiped and stowed away on the shelf of the dresser-that brought nearly 3 o'clock, p.m. On that remarkable occasion and about that time I made my first appearance on the stage of action, but as a new comer I was in a pitiable plight and destitute condition, for I was naked as a rat, without a cent of money and no pocket to put it in if I had a copper.

But I fell into good hands-was well clothed and fed, grew a little, and I have weathered the storms of seventy-four winters and summers, having retained by eyesight, hearing, smelling, taste and appetite in a remarkable manner, and scandal says yet very fond of a good cup of coffee.67

Unfortunately, being Sheriff of Hardin County occasionally required Samuel Haycraft, Sr. to perform some unpleasant duties. On 30 December 1796 "Jacob, a negro slave, the property of John Crow, killed his master." That day, probably in some wooded area, both men were reportedly "cutting on the same fallen tree-the negro at the butt end, the master high up," when Crow, believing that his slave was not working hard enough, stopped to examine Jacob's work and rebuked him for his purported "sloth." When Crow turned around to return to his own work, the black man reportedly struck him from behind with an axe blow to the head, killing him instantly.68

Although Jacob ran away, getting as far as Vienna, "at the falls of Green River," he was apprehended by Phillip Taylor, who brought him back to Hardin County. When arrested, Jacob reportedly said in a defiant tone, "I killed Crow, but you prove it."69

On 02 March 1796, at a court presided over by Judges Thomas Helm and John Vertrees, Jacob "pleaded guilty, and…was sentenced to be hung by the neck until he was dead, dead, dead." Sheriff Haycraft "was ordered to carry the sentence into execution on the second day of April, 1796, between the hours of twelve and two o'clock." Owing to the rarity of such an event, "it produced quite a sensation [in the community], and particularly so, as John Crow was a man of some note and highly esteemed."70

During the time the convicted slave "was confined in the old poplar log jail," it fell to Samuel Haycraft and a guard to keep an eye on him and attend to his needs. One day, it fell to Peggy Haycraft to feed the prisoner, owing to her husband "being absent" for some reason. When the guard opened the cell door, "the prisoner made a desperate dash, upset the old lady and ran for life." He did not get very far. Thomas Helm, "a stout young man," ran after Jacob, caught him after he had gone about four hundred years and managed to bring him back to the jail, where he remained until the date set for the execution, which was to be carried out in public, according to the custom of the time.71

Because he had "a distaste for the hangman's office," on the day of the execution Samuel Haycraft, with the consent of the prisoner, "procured the services of a black man to tie the noose and drive the cart from underneath."72

Another distasteful duty that Sheriff Haycraft was required to carry out was seizing and selling the property of citizens who were unable to pay their back taxes, a job he may have found a little easier to contend with than hanging a man. On 28 September 1796, Sheriff Haycraft drew up a notice, which was printed in the 22 October issue of the Kentucky Gazette, listing numerous tracts of land that were "to be sold to the highest bidder for cash at Hardin court house, on the fourth Tuesday in November next (it being a court day)."73 Interestingly, the list of scofflaws included the heirs of a woman named Elizabeth Eaton, who although the name was identical, was unlikely to be the same Elizabeth Eaton who had been transported from London in 1744 along with his father James Haycraft and Samuel Smytheman (for whom it is possible he was named).

During his lifetime, Samuel Haycraft himself owned hundreds and sometimes thousands of acres of Hardin County terrain. Although there is no record of any land grant for him in the holdings of the Library of Virginia-as there are for some of the other early settlers of Hardin County (which seems a little surprising), there are some in the archives of the State of Kentucky and no fewer than thirty-one deeds on file in the office of the Hardin County clerk, dating from 1798 through 1820, in which he is named as the seller and no less than thirty-six in which he is named as the buyer. The earliest of these transactions, dated 08 November 1798, records the sale of 300 acres of land by Samuel to his brother Joshua.74 Another records the sale of land to his son Samuel Jr., for the nominal sum of one dollar. One deed concerns the sale of land by Samuel Sr. to another of our ancestors, Thomas Gilliland, whose granddaughter Sarah, or "Sally," later married Samuel Sr.'s namesake grandson, Samuel Haycraft Morrison (son of daughter Betsey and her husband Isaac Morrison).75 Unfortunately, even a short synopsis of all these various transactions would probably require another essay that might rival the length of this one.

In 1796 Samuel Haycraft, who was obviously prospering, built a new house to replace the rustic log cabin that he and his family had called home during the early years of their residence in the area. According to Samuel Jr., the new dwelling not only had a basement but also was two stories high, "with a stone chimney" that "took more than one hundred wagon loads to build it." In those days, such a thing: "was considered…rather aristocratic."76 No doubt the Haycraft residence was one of the finer homes in Elizabethtown, which was formally established on 04 July 1797, four years after it was first laid out by Andrew Hynes.

|

The Lincoln-Haycraft Connection

Our ancestor, Samuel Haycraft, not only lived in the same county (Frederick) as George Washington, when he (Samuel) was growing up in colonial Virginia, he also had a connection with the family of Abraham Lincoln, who was born in Hardin County in February 1809. A historical marker in Elizabethtown recalls that in 1796, when Samuel established the first mill in the Severns Valley, he employed Abraham Lincoln's father, Thomas Lincoln, to help him build it. (See photo below.) He also sold a town lot to the first husband of Lincoln's stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston, later sold by Thomas Lincoln and his wife Sarah to another Elizabethtown resident. During the Civil War, Samuel Haycraft, Jr. corresponded with Lincoln. Our ancestor, Samuel Haycraft, not only lived in the same county (Frederick) as George Washington, when he (Samuel) was growing up in colonial Virginia, he also had a connection with the family of Abraham Lincoln, who was born in Hardin County in February 1809. A historical marker in Elizabethtown recalls that in 1796, when Samuel established the first mill in the Severns Valley, he employed Abraham Lincoln's father, Thomas Lincoln, to help him build it. (See photo below.) He also sold a town lot to the first husband of Lincoln's stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston, later sold by Thomas Lincoln and his wife Sarah to another Elizabethtown resident. During the Civil War, Samuel Haycraft, Jr. corresponded with Lincoln.

The author at the Lincoln-Haycraft Bridge, Elizabethtown, Kentucky, June 2012.

|

During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, Samuel Haycraft became briefly involved in state as well as county-level politics. In 1801, the same year that Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated as the third President of the United States, the Kentucky Gazette announced that he [Samuel] had been elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives to represent Hardin County. That November, after taking his seat in the legislature, he participated in a three-day debate on whether or not to establish circuit courts in Kentucky. Eventually, he joined twenty-two of his fellow representatives in voting "yea." However, thirty-four members who voted against the measure outnumbered them and so it did not pass.77

Early the next year, during the March 1802 term of the Hardin County court, Samuel Haycraft "produced commission and took his seat as quarter session judge." Later that same year, in December, the Kentucky state legislature "abolished the quarter session courts," establishing district courts in their place. The following spring, on 18 April 1803, "the Hon. Stephen Ormsby, circuit judge, and the Hon. Samuel Haycraft, and William Mumford, assistant judges, organized the first circuit court in Elizabethtown."78 Throughout the remainder of the decade, Haycraft served in this same capacity, sometimes assisting the circuit judge and sometimes, in the circuit judge's absence, conducting the court himself, along with one other assistant judge.79

In August 1809, during the first administration of President James Madison, Samuel Haycraft, ran again for election to the Kentucky House of Representatives, along with Charles Helm and John Thomas. At first, as reported in the Kentucky Gazette,80 it appeared that he and Helm were going to serve together, since both men had received more votes than Thomas and also because each county was then entitled to two representatives; but that is not the way things turned out. Here is how the episode was reported in a biography of Henry Clay, who had not yet been elected to federal office and was then serving in the Kentucky legislature, and who also chaired a committee the job of which was to decide what to do under the circumstances:

The citizens of Hardin County, who were entitled to two Representatives in the General Assembly, had given 436 votes for Charles Helm, 350 for Samuel Haycraft, and 271 for John Thomas. The fact being ascertained that Mr. Haycraft held an office of profit [i.e., assistant judge] under the Commonwealth at the time of the election, a constitutional disqualification attached and excluded him. He was ineligible, and therefore could not be entitled to his seat. It remained to inquire into the pretensions of Mr. Thomas. His claim could only be supported by a total rejection of the votes given by Mr. Haycraft as void to all intents whatever. Mr. Clay contended that those votes, though void and ineffectual in creating any right in Mr. Haycraft to a seat in the House, could not affect, in any manner, the situation of his competitor. Any other exposition would be subversive of the great principle of Free Government, that the majority shall prevail. It would operate as a fraud upon the People; for it could not be doubted that the votes given to Mr. Haycraft were bestowed under a full persuasion hat he had a right to receive them. It would, in fact, be a declaration that disqualification produced qualification-that the incapacity of one man capacitated another to hold a seat in that House. The Committee, therefore, unanimously decided that neither of the gentlemen was entitled to a seat.81

As a consequence of this decision, "a new election was ordered." This time, even though he had in the meantime resigned his judgeship, Haycraft was beaten by just "a few votes," owing largely to "the extraordinary efforts of Thomas' friends."82

The following year (1810), Samuel Haycraft ran again for the state legislature and this time, he won. Afterward, he and Helm, who won re-election, went to Frankfort, where upon taking his seat in the House of Representatives, Samuel Haycraft was assigned to serve on the Committee for Propositions and Grievances.83

During the 1810-1811 session of the state legislature, the members considered a bill that would have effectively outlawed the slave trade in Kentucky by restricting the importation of slaves into the state as merchandise, although it did not propose to ban slavery altogether. More interestingly, it would have allowed the state to confiscate any illegally imported slaves and sell them at auction to the highest bidder, with the money to go into the state treasury. When the vote was taken, in January 1811, Samuel Haycraft joined with thirty-six other legislators to defeat the measure (only twenty-seven voted "yea").84 Samuel himself was a slaveholder (the 1810 federal census shows he owned at least two).85 Did he vote the way he did because he had no objection to the sale of slaves in Kentucky? Or was it because the bill had the potential to turn the state in a slave-trader? In the absence of his own words on the subject, it is impossible to know his precise reasons for opposing the bill since it did not outlaw slavery altogether.

That same year (1811), Samuel Haycraft, Jr., now seventeen, "was sworn in as deputy clerk."86 Researchers delving into their family's history in Hardin County will find his signature on most the official documents of the county for a number of decades.

During the final decade of his life, it appears that Samuel Haycraft retired from politics. However, he continued to buy and sell land. He this and the previous decade he and his wife also saw their children coming of age and getting married and starting families of their own. (By this time he and Peggy were already grandparents.) One joyous moment came in 1814, when the couple's next-to-youngest son, Samuel Jr., was married to Sarah Brown Helm, daughter of Judge John B. Helm and granddaughter of John Helm and his wife Sarah, who had themselves been married in 1789 at Haycraft's fort.87

There were also a few occasions for sadness. In 1813, Joshua Haycraft, Samuel's younger brother, reportedly died at Leitchfield, in Grayson County, Kentucky.88 (Grayson County was formed from the western part of Hardin County and a portion of the eastern part of Ohio County in 1810.)

In 1818 the United States Congress passed a law granting pensions to veterans of the Revolutionary War who were not disabled. At the age of sixty-eight, Samuel Haycraft applied for a pension and in March 1822, after he had been approved at a rate of $8 per month, received arrears dating to 20 June 1820 in the amount of $163.96, which in those days was a considerable sum of money. He continued to receive this amount ($8 per month) until his death, in Hardin County, on 15 October 1823.89

Following her husband' death at the age of seventy (nearly seventy-one) and his burial in the Elizabethtown city cemetery, Peggy Haycraft applied for a federal widow's pension, which was approved, and which she received until her own death at the age of eighty-three on 12 April 1843.90 She was afterward buried beside her husband in the Elizabethtown city cemetery.

Above: Samuel Haycraft, Sr. is buried with his wife Peggy in the Elizabethtown City Cemetery. Photo by the author, taken June 2012.

NOTES

1Haycraft Family Bible, Family Record "Births" page included as part of Margaret Van Meter Haycraft's application for a Revolutionary War pension based on her husband's service. In his celebrated book about the history of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, Samuel Jr. erroneously reported that his father was born on 11 September; see Samuel Haycraft, Jr.. Haycraft's History of Elizabethtown, Kentucky (Hardin County Historical Society, 1960), 121.

2Ibid.

3J. M. Armstrong, Biographical Encyclopedia of Kentucky of the Dead and Living Men of the Nineteenth Century (Cincinnati, Ohio: 1878), 222.

4Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, 09 June 1774, 2.

5Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck, Virginia's Colonial Soldiers (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1988), 141-2.

6Samuel Haycraft, Revolutionary War service record and Samuel Haycraft and Margaret Haycraft, Revolutionary War Pension file, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

7Ibid.

8Neville B. Craig, The History of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: John H. Mellor, 1851), 85-6.

9Ibid., 111.

10Ibid., 122.

11Ibid., 128 and 138-9.

12Ibid., 149.

13Samuel Haycraft, Revolutionary War service record and Samuel Haycraft and Margaret Haycraft, Revolutionary War Pension file, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

14Samuel Hazard, Pennsylvania Archives, Vol. VII (Philadelphia: Joseph Severns & Co., 1853), 560.

15

16Craig, 147-8.

17Ibid., 148.

18Ibid.

19Louise Phelps Kellogg, ed., Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volume XXIII, Draper Series, Volume IV, Frontier Advance on the Upper Ohio, 1778-1779 (Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1916), 159-60.

20Ibid., 160.

21Ibid.

22George Washington to Daniel Brodhead, May 3, 1779, the George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799 [Accessed 01 March 2012.]

23William L. Stone, Life of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) including the Border Wars of the Revolution (Albany, New York: J. Munsell, 1865), 396-7.

24Kellogg, 251.

25Stone, 398; Note: In a letter to Col. Archibald Lochry, dated 29 January 1779, in which he states the ambush took place about three miles from Fort Laurens, General McIntosh says that only two men were killed and that four were wounded and one taken prisoner, see Kellogg, 210.

26Stone, 398.

27Ibid.

28Kellogg, 257.

29Stone, 398.

30Ibid., 399.

31Kellogg, 200.

32Ibid., 257.

33Samuel Haycraft, Revolutionary War service record, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

34Kellogg, 306-7.

35Don Corbly, Pastor John Corbly (Don Corbly, 2008), 135.