|

By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. To Whom It May Concern: I previously thought I might be descended from this individual, but I know now (as of March 2019) that I am not. I have left this biography online, however, in case it might be helpful to someone who is related to or descended from him. References to my previous suppositions have been struck through with a horizontal line.

Kinard (or Kennard) Butler was born, almost certainly in North Carolina, about 1800.2 His father was Isaac Butler,3 who I think might be the same Isaac Butler of Bertie County, North Carolina who served as a Revolutionary War soldier in the Fourth North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army under the command of General George Washington at Valley Forge and elsewhere. The name of Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's mother is presently unknown but there are two reasons why I suspect that Kinard (or Kennard) was her maiden name: First of all, Kinard (or Kennard) is an uncommon first name. Secondly, it was not unusual in this era for a couple to acknowledge or honor the wife's family by bestowing her maiden name on one of the children as a first name. (Some people still follow this tradition. For example, my eldest son's middle name is my paternal grandmother's maiden name.) Finally, census and other records reveal that there were a number of individuals bearing the surname Kennard (or Kinnard) living in Greene County, Alabama during the same time that the Butler family were resident there. Although this may only be coincidental I think it is possible (though so far unproven) that they were Isaac Butler's in-laws.4

Kinard (or Kennard) Butler had two brothers, John and Isaac, and three sisters: Cynthia, who married John Layton; Mary or Polly (born about 1812); and Susanna, who married a man whose surname was Murray.5 Unfortunately, all my efforts to find out more about them (so as to locate their descendants for the purpose of sharing family history information) have met with failure. Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's wife was Nancy Ann Johnson, the daughter of a Revolutionary War veteran named Richard Johnson and his wife Sarah.6 She was born in 1796 in Virginia7 (probably in Southampton County). The date and place of Kinard (or Kennard) and Ann's marriage is presently unknown but I speculate that it took place in either Bertie County or Cumberland County, North Carolina about 1823. Together, they had two sons My best guess is that Kinard (or Kennard) Butler and his family removed from North Carolina to Greene County, Alabama about 1825. It appears that Kinard (or Kennard)'s father, Isaac Butler, who was probably a widower,9 also migrated to Alabama around this same time or even perhaps a little earlier. The reason for such a move is not hard to find. "Between 1815 and 1835," writes author Blackwell P. Robinson, "North Carolina was so undeveloped, backward and indifferent to its condition that it was often called the "Ireland of America" and the "Rip Van Winkle" state." Consequently, he commented, "North Carolina dropped in population from fourth place among the states in 1790 to seventh place in 1840, though it had about the highest birth rate in the nation. Soil exhaustion, the lure of fertile and cheap lands in the west, the lack of internal improvements and educational facilities and unhappy conditions generally led many people to leave the state."10

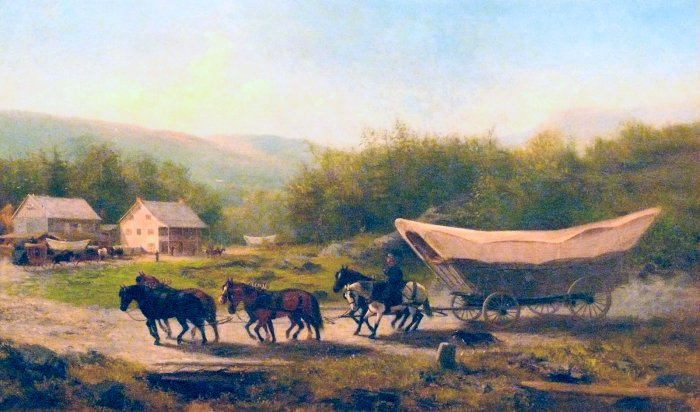

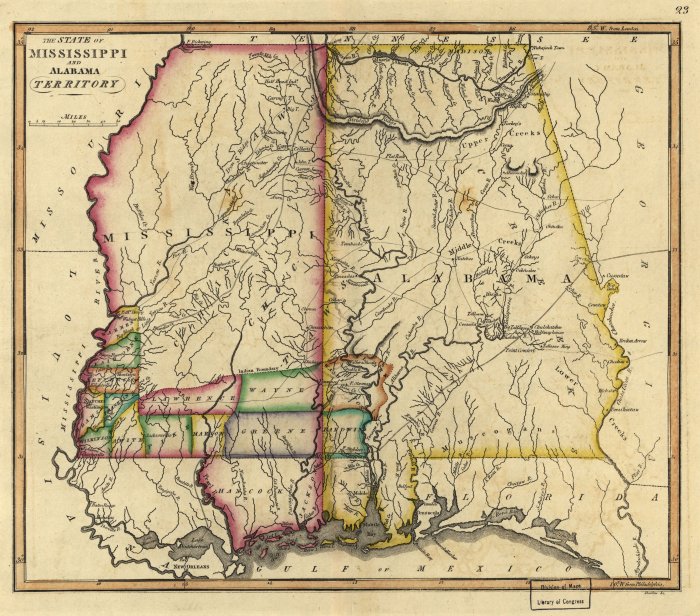

Frequently, these migrants' destination of choice was the former Mississippi Territory, which on March 3, 1817 was divided by the Federal government into two portions. The western half was admitted to the union as the State of Mississippi on December 10 that same year, while the eastern half was organized as the Territory of Alabama. Two years later, on December 14, 1819, Alabama too was admitted as a state. According to author William A. Owens, the largest number of settlers came from southern Virginia and the Carolinas.11

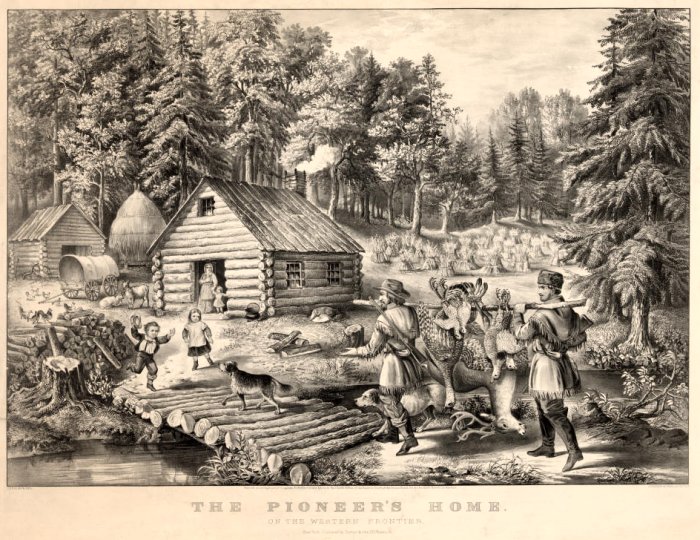

"They entered Alabama," wrote Owens, "by way of the Tennessee and Alabama rivers." Or they traveled by land, the poorest on foot, those better off by wagon train, taking "either the upper road or the Fall Line Road, both of which began in Virginia, crossed North and South Carolina and intersected at Montgomery, Alabama."12 As "mighty streams of emigration" poured into the state, "spreading over the whole territory of Alabama, the axe resounded from side to side and from corner to corner. The stately and magnificent forest fell. Log cabins sprang, as if by magic, into sight. Never before or since, has a country been so rapidly peopled."13

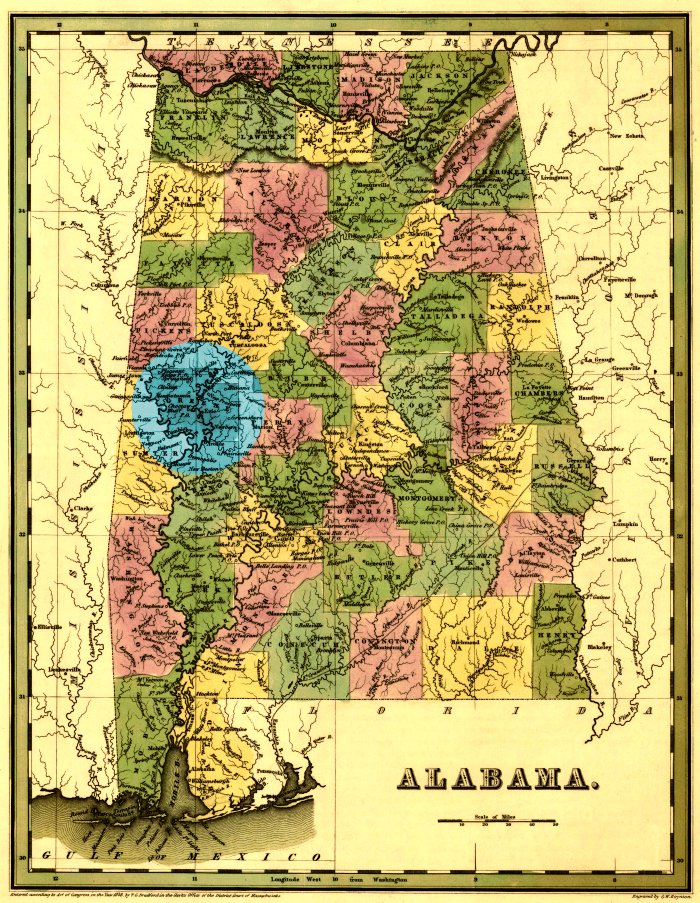

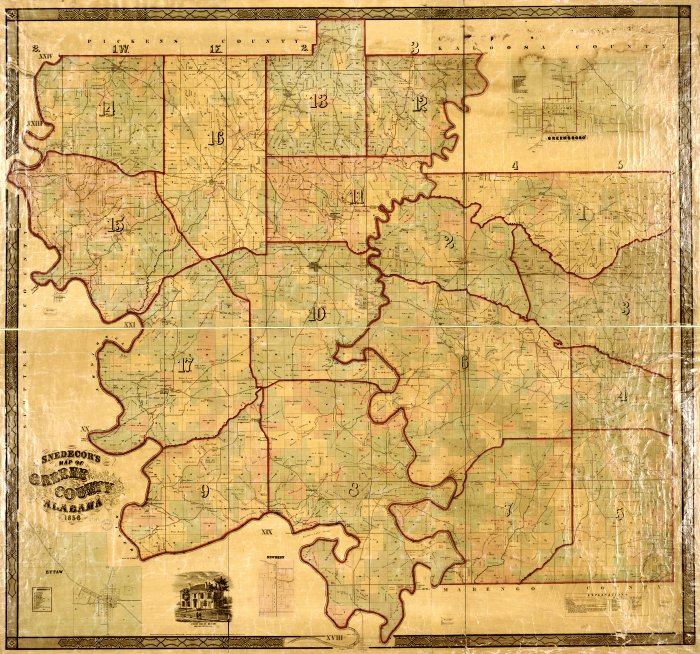

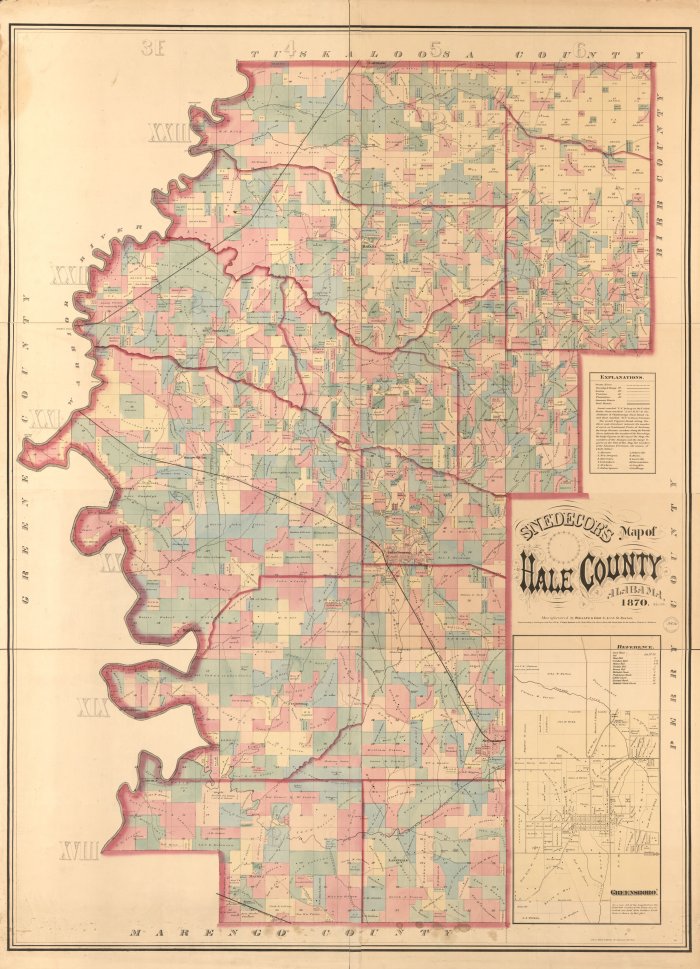

It is possible that the Butler family did not migrate directly to Alabama. Some early settlers moved west incrementally, settling first in South Carolina, Georgia, or Tennessee, before taking up permanent residence in Alabama.14 Many families also moved around within the state, residing for short periods in one or more different counties before finally finding one that seemed to suit them. In any event, we can be sure that by 1827 the family of Kinard (or Kennard) Butler was living in Greene County, Alabama.15 Established by an act of the Alabama legislature on December 13, 1819, Greene County was originally much larger than it is today. Formed out of land taken from Marengo and Tuscaloosa counties, Greene too was reduced in size when present-day Hale County, its eastern neighbor, was organized in 1867. Other counties with which it shares a boundary today are Pickens and Tuscaloosa to the north and to the west and south, Sumter and Marengo. In all, modern-day Greene County has an area of about 650 square miles. Of all Alabama counties Greene is arguably the most oddly shaped, which is the result of its natural boundaries-the Tombigbee River on the west, the Sipsey River on the north and to the east, the Black Warrior River. At the county's southernmost point the Black Warrior and Tombigbee converge. This is where the town of Demopolis is situated. The original county seat was the now non-existent town of Erie, established as a river port in 1819. Eutaw, founded in 1838, is the present county seat. It is located near the center of the county.

Greene County's terrain, which lies in the heart of Alabama's so-called "Black Belt," is largely level or gently rolling land, with the soil of the prairies and bottoms of the Tombigbee-Black Warrior fork being especially rich and fertile. During the nineteenth century, corn and cotton were among the principal crops grown there, making Greene, as late as 1845, the foremost agricultural county in the state of Alabama. Greene County was named for General Nathaniel Greene, Washington's second-in-command during the American Revolution and the present county seat, Eutaw, was named for the site of Greene's greatest victory against the British-the 1781 Battle of Eutaw Springs in South Carolina. Two different Butler families resided in Greene County during the early years of settlement. David Butler, a South Carolina native, headed one. Due to the fact that all of David Butler's children (along with other miscellaneous family members) can be accounted for in various public records, we can confidently rule out a father-son relationship to Alfred Butler. The main reason I feel so strongly that Kinard (or Kennard) Butler is my third great-grandfather, in spite of a lack of documentary evidence, is because he was the only early-day Greene County resident bearing the surname Butler with two sons about the same age as my second great-grandfather and his presumed brother, who cannot otherwise be accounted for. Our first known mention of Kinard (or Kennard) Butler in any public record is his father's undated will, which was entered for probate during the May 1827 term of court in Greene County, Alabama, which suggests that Isaac had died sometime that spring. The will, which was brought to the court's attention by Isaac's son-in-law John Layton, lists Kinard (or Kennard) Butler and all his siblings (as noted above) as heirs and names Layton and a man named John May as executors.16 During the November 1827 term of the Greene County court, Kinard (or Kennard) Butler contested the validity of his father's purported will, which resulted in a continuance of the case until the next regular term, scheduled for January 1828.17 I suspect this action was taken because the unsigned will produced by Layton gave Kinard (or Kennard)'s sister all five of their father's slaves, who seem to have constituted his only valuable property. At the same session the court appointed John Layton administrator "for the purpose of collecting & preserving the property of Isaac Butler" and also heard the plea of John May, who personally appeared "and refused to serve" as an executor of Isaac Butler's estate, although it had apparently been Butler's wish that he do so.18 Between the November and December 1827 sessions of the court, Layton inventoried Isaac Butler's estate, which consisted of five slaves as well as the sort of personal property a Southern frontier farmer would be expected to own, such as a cotton gin, some cotton seed, household furniture, a wagon, three horses, some pigs, a plow, a saddle and bridle, and several other miscellaneous small items including tin boxes, an umbrella and three books. Interestingly, there is no mention of any real estate in the inventory, nor in the will, which suggests that Isaac Butler may have been living with one of his adult children (Kinard (or Kennard) or daughter Cynthia more likely) when he died at a relatively advanced age. This inventory, the total value of which was estimated to be $1,807.92½, was written into the record of the Greene County court after it met on December 22, 1827.19 At the county court session held on January 22, 1828 Layton again produced the undated, unsigned will of Isaac Butler whereupon Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's unnamed attorney "opposed" it by producing "as a revocation thereof, an instrument of writing bearing date the 14th day of September 1826, signed by the said Isaac Butler" and authenticated by three witnesses. Incredibly, after John May testified under oath that he had "drawn [up] the instrument" produced by Layton and verified that it was "the last will and testament of said Isaac Butler" and after "divers other witnesses" also testified, a jury decided in favor of Layton, whereupon the court ordered the unsigned will to be entered into the record.20 Unfortunately, the will produced by Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's attorney appears to have been lost to history. It would be interesting to see how it differed from the one that the court accepted. We may imagine that it was more advantageous to Kinard (or Kennard), otherwise why would he have contested the other will? The will accepted by the court gave all of Isaac Butler's five slaves (valued at $1,400 altogether) to his daughter Cynthia, also known as "Sythy," and a bed and furniture to Polly. It concluded with Isaac Butler's wish that the remainder of his property be sold and the proceeds divided among his other children, "to wit, John, Isaack and Kennard Butler and Susanna Murray." Layton and May, as previously noted, were named executors.21 At this or a later session, the court appointed John Layton guardian of Isaac Butler's fifteen-year-old daughter Mary or "Polly" (who was married on February 28, 1828 to a young man named Thomas C. Sparks) and also authorized him to sell his father-in-law's personal estate, so that Isaac Butler's debts could be paid, as the decedent had instructed in his will. This was done during 1829 and 1830. Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's father-in-law, Richard Johnson, who was among the claimants, was paid $1.00 in 1829. Kinard (or Kennard) himself received a little more than $14 in December 183022. At a special session held on May 15, 1829, the Greene County court further authorized John Layton to sell three of the slaves his wife "Sythy" had inherited (seven-year-old George, twenty-five-year-old Tabitha, and her eighteen-month old son William) at the courthouse door in Erie (which was then the county seat), after giving fifteen days' notice. The purpose of this sale, according to court records, was to raise more money to pay Isaac Butler's debts, which the proceeds from the sale of his personal estate had apparently not covered.23 In the 1830 federal census for Greene County, Alabama, the only one in which Kinard (or Kennard) Butler is listed by name, his household included two males under five years of age (probably Alfred and Levin), one male age 20 to 30--obviously Kinard (or Kennard) himself, two females under five (almost certainly Lovely and Jully), three females age 5 to 10 (identities unknown), one female age 10 to 15--perhaps Kinard (or Kennard)'s sister Mary, and two females 30 to 40 (one of these is obviously his wife Nancy Ann but the identity of the other is unknown), for a total of eleven persons.24 Unfortunately, apart from revealing that Kinard (or Kennard) Butler also owned no slaves, the 1830 census provides us with no other information, unlike later censuses, which give a person's occupation, the value of their property, and so on. Although we may guess that Kinard (or Kennard) Butler was a farmer, as were most other Americans in that age, but there is no way to be certain. He could just as easily have been an artisan or craftsman of some kind. The town of Erie, which was then a bustling river port, had approximately 1,500 residents. In May 1996 I did extensive research in the Greene County courthouse in Eutaw, Alabama and found no deed records on file for Isaac, Kinard (or Kennard), or Ann Butler, which leads me to believe that they were townspeople. The fact that neither Kinard (or Kennard) nor Ann owned any slaves, so far as it is known, also suggests that they were people of modest means. Unfortunately, the only other public records in Greene County that mention Kinard (or Kennard) Butler are the estate inventories of some other residents, which merely list him as a claimant. The latest of such claims, in respect to the estate of one Lewis A. Stolenwerck, is dated May 25, 1835.25 After that, there is nothing. The fact that Kinard (or Kennard)'s wife Ann is listed as the head of a Greene County, Alabama household in the 1840 federal census and Kinard (or Kennard) himself is conspicuously absent from this or any subsequent censuses, leads to but one conclusion: Kinard (or Kennard) Butler died sometime between 1835 and 1840, but when and where and how? Unfortunately, there is neither a will nor any probate records regarding the estate of Kinard (or Kennard) Butler in the Greene County courthouse that might provide the answers. Furthermore, his name cannot be found on a tombstone in any Greene County cemetery that has been searched and indexed. Wondering if he might have died in the Texas Revolution of 1835-1836, I examined the casualty lists of that conflict but his name is not on any of them; nor does his name appear on any roster of the volunteers who fought in the 1836 Creek Indian War in Georgia and Alabama. The only other plausible explanation is that he simply succumbed to some illness and was buried somewhere in Greene County without a headstone to mark his grave (or if a marker was erected, it has since fallen down and been covered with earth, where it cannot be seen). Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's wife survived him by more than four decades. In 1840, the same year that Ann Butler was named as head of the household in the federal census (with two sons and two daughters, all age 10 to 15),26. One the girls, Lovely, was married to Robert Johnson (probably a cousin), on August 13, 1840.27 Owing to the fact that there is no record of marriage for Jully Butler in Greene County (or anywhere else, so far as it is known) and no listing for her in any subsequent census, we may assume she died either shortly before or shortly after reaching adulthood.

Federal census records reveal that by 1850 Ann Butler was living with her daughter Lovely and son-in-law Robert Johnson, a gin-maker, and their children, Cornelia and Charles.29 Ten years later, at the age sixty-five, Ann (or "Nancy A." as she was enumerated), was living on her own in the town of Greensboro. Interestingly, Henry Stolenwerck (probably a son of Lewis) and his family were among her closest neighbors.30

At age seventy-five, Ann Butler was enumerated in the 1870 federal census for Hale County, Alabama (created in 1867 out of a portion of Greene County) with an African-American family, Betty and Sam Douglass, former slaves who lived in Greensboro, apparently residing in close proximity to Ann's daughter Lovely Johnson and her family, which by this time included, in addition to the oldest two children, three sons named Frank, Thomas, and Eddie and four girls: Amanda; Mary; Margaret; and Fannie. It is my guess that Betty and Sam Douglass, who had two young children of their own, were hired by Lovely and her husband to live with and look after the now-elderly Ann (or perhaps they had been hired by Ann herself). In the census, Betty's occupation is given as "Domestic" and Sam's as "Jobber."31

Our last official mention of Ann Butler is the 1880 federal census for Hale County, Alabama, which found the then-eighty-four-year-old woman living with her recently-widowed daughter, Lovely, and eight Johnson children still at home, including the oldest, Cornelia, who apparently never married.32 Lovely's husband Robert, who had served as an officer in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, had died earlier that same year, on April 15, at age sixty-five.33 During a research trip to Alabama in 1996, my father and I visited the New Greensboro Cemetery in Greensboro, Hale County, where in lot number 162 we saw for ourselves the best evidence that Ann Butler was the widow of Kinard (or Kennard) Butler and the mother of Lovely Butler Johnson. Four gray weatherworn tombstones or grave markers, stand in a row. Each is between two and three feet tall. The inscription on the one at far left reads: ANN BUTLER, WIFE OF K. BUTLER, BORN MARCH 11, 1796, DIED FEB. 17, 1882, AGE 85. Beside it is a slightly taller, grayish stone that marks the grave of: LOVELY UNITY BUTLER, WIFE OF ROBERT JOHNSON, BORN APRIL 26, 1824, DIED MARCH 30, 1894. Next in line is a headstone inscribed with these words: ROBERT JOHNSON, BORN IN NORTH CAROLINA, FEB. 19, 1815, MARRIED IN GREENSBORO, ALABAMA, AUGUST 13, 1840, DIED APRIL 15, 1880, AGED 65, C.S.A. The fourth headstone, which bears the inscription SYDNEY NELSON, BORN June 10, 1859, DIED October 16, 1897, marks the grave of one of Lovely and Robert Johnson's adult sons.34

NOTES 1I first began to consider the possibility that Kinard (or Kennard) Butler might be the father of Alfred Butler on March 3, 1992, following a day of research at the downtown Dallas, Texas public library. After more than twenty years of intermittent further research, I am now satisfied that no one else is a more likely candidate. 2U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fifth Census of the United States, 1830: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 373. 3Will of Isaac Butler, Will Book B, page ?, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 4John and Anthony Kinnard were early-day residents of Erie, Alabama, the original seat of Greene County. See The Heritage of Greene County, Alabama (Clanton, Alabama: Heritage Publishing Consultants, Inc., 2001), 4. The 1830 census for Greene County lists several other individuals with the surname Kennard or Kinnard. See also: William Edward Wadsworth Yerby, History of Greensboro, Alabama from Its Earliest Settlement (Montgomery, Alabama: The Paragon Press, 1908), 2. 5Will of Isaac Butler, Will Book B, page ?, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 6Will of Richard Johnson, Will Book B, page 265, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama; Will of Sarah Johnson, Will Book C, page 84, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw Alabama; Ann Butler headstone, Lot 162, Greensboro City Cemetery, Greensboro, Hale County Alabama. 7Ann Butler headstone; U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 299. 8U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fifth Census of the United States, 1830: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 373; Deed from Richardson Johnson to granddaughters, Loudy Unity Butler and Jully M. Butler, Deed Book C, page 269, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 9No wife is mentioned in Isaac Butler's will, which leads me to believe his wife died before he moved to Alabama. 10Blackwell P. Robinson, ed., The North Carolina Guide (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1955), 76-7. 11William A. Owens, A Fair and Happy Land (New York: Scribner, 1975), 204. 14I've looked for but not found any evidence of this, however. 15This is verified by Kinard (or Kennard) Butler's contesting of his father's will in Greene County court in November 1827. 16Will of Isaac Butler, Will Book B, page ?, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 17Orphans Court Records, Book ?, page 203, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 18Ibid, pages 204 and 215. 19Will of Isaac Butler, Will Book B, page ?, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 20Orphans Court Records, Book ?, page 231-2, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 21Will of Isaac Butler, proven January 22, 1828. Office of the Judge of Probate, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 22Ibid.; "Greene County Marriages, 1836-1848." Alabama Genealogical Register, Columbus, MS, vol. 10, nos. 2 & 3, June 1968, 114. 23Orphans Court Records, Book ?, page 349, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama.24U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fifth Census of the United States, 1830: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 373. 25Orphans Court Records, Book ?, page 858, Greene County courthouse, Eutaw, Alabama. 26U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 107. 27"Greene County Marriages, 1836-1848," Alabama Genealogical Register, Columbus, MS, vol. 10, nos. 2 & 3, June 1968, 114. 28I refer the reader to my book, A Home in Texas (Richardson, Texas: Shoestring Books, 1994). 29U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 299. 30U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Population, Greene County, Alabama, 30? 31U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States, 1870: Population, Hale County, Alabama, 54-5. 32U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Tenth Census of the United States, 1880: Population, Hale County, Alabama, 4. 33Robert Johnson headstone, Lot 162, Greensboro City Cemetery, Greensboro, Hale County Alabama. 34Author personal visit to Greensboro City Cemetery, Greensboro, Hale County, Alabama, May 28, 1996.

This website copyright © 1996-2019 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |