|

The Lowry Family

Lowry Family By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. I am related to the Lowry family by virtue of the marriage of my grandfather William Ollie Jenkins to Ida Lee Seay, who was the daughter of Margaret Inez (Ward) Seay, who was the daughter of Mary Ann (Lowry) Ward, who was the daughter of Mark Lowry, who was the purportedly the illegitimate son of Sarah Ann "Sally" Lowry and Jacob Reed. In public records this surname, which is Scots-Irish in origin, is sometimes spelled "Lowrey" or Lowery" but the best evidence I have is that "Lowry," without an "e," is the correct spelling for our line. The Lowrys were a very prolific family, with an unfortunate propensity for bestowing many of the same given names on their children down through the generations (and often within the same generation, with cousins all giving their sons and daughters many of the same names). For this reason, it is obviously very difficult keeping them all straight the further one goes back in time. This leads me to fear that many researchers have both made and perpetuated some errors. Consequently, I have tried to be careful and in the process, I hope that I have corrected some mistakes rather than made them. SARAH ANN LOWRY Sarah Ann Lowry, born 1794 in South Carolina, was reportedly the fifth child of Charles Lowry Jr. and his wife whose name was also Sarah.1 According to one of the same sources remarked upon in the previous two sections, the Charles Lowry Jr. family was living in Newberry District, South Carolina when the 1790 federal census was taken, and in Laurens District South Carolina when the 1800 census was taken.2 In 1821, when she was 27-years-old, Sarah Ann Lowry reportedly gave birth to an illegitimate child by a man named Jacob Reed, who she is said to have later married in 1828 in Jackson County, Georgia.3 This same source holds further that the child, who was named Mark Lowry, was also named or nicknamed "Sam" and that he was the only one of the seven children living in Jacob and Sarah Ann's household who bore their mother's maiden name rather than their father's surname. The names of Sarah Ann's other six children were:

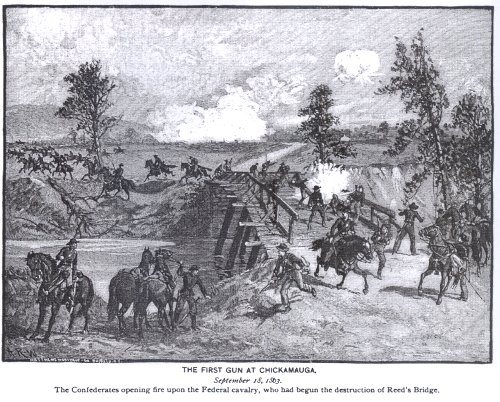

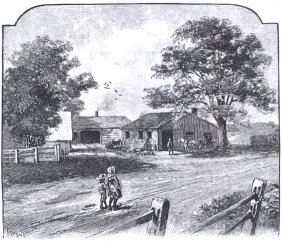

One of the same sources that provided the information above states that the father of all these children, Jacob Reed, was born 12 July 1804 and died May 1860 and that their mother, Sarah A. Lowry, was born in 1797 and died on 6 August 1870.5 The 1860 and 1870 federal census records for Catoosa County, Georgia, where the Jacob and Sarah Reed family was residing in those particular years corroborates much of the above information regarding the Reed family.6 Unfortunately, it has so far proved impossible to find the Reed family in earlier census records but I believe this is probably due to an error in the indexing process and not to any omission by the census bureau. In 1863 the recently widowed Sarah Reed (Jacob died in May 1860) was living on a farm on the east bank of Chickamauga Creek, in Catoosa County, Georgia, when the famed Civil War battle of the same name began almost literally on her doorstep. It all started in September 1863 when Confederate troops under the command of General Braxton Bragg evacuated nearby Chattanooga in the face of an advancing federal army commanded by General William Rosecrans. As Bragg and thousands of Confederate soldiers came rushing into the valley through which Chickamauga Creek previously flowed peacefully (it would later be called "the River of Death"), skirmishes between these troops and pursuing federal soldiers began to take place, culminating on in the bloody Battle of Chickamauga, which began at Reed's Bridge, a short wooden plank crossing that spanned the creek near Sarah Reed's farmhouse. The cannon that fired the opening shot of the battle was reportedly positioned in her front yard.7 A book that was sold as a souvenir of the 1895 Atlanta Cotton Exposition, Mountain Campaigns of Georgia, tells the story of what happened there:

One of the most notable casualties of the Battle of Chickamauga was Confederate General Ben Hardin Helm of Kentucky, who happened to be the brother-in-law of President Abraham Lincoln. After Helms received a mortal wound on the battlefield, he was taken to the Reed House, which had been converted into a makeshift Confederate field hospital by General Breckinridge. According to family lore, Sarah Lowry Reed nursed the wounded general herself before he died.9 Family lore also holds that three of Sarah's sons, James, Thomas, and Monroe, all participated in the Battle of Chickamauga, where James, Sarah's second oldest son, was also reportedly wounded. Family lore holds further he, and not his mother, was the actual owner of the Reed family farm at the time of the battle, that his father had sold him the land earlier but that the parents continued to occupy the property. Although James J. Reed's Confederate service record says nothing about Chickamauga, it does confirm that he was wounded at the Battle of Jonesboro, Georgia on 31 August 1864 and that he never returned to active duty afterward.10 According to one of the Michigan soldiers who fought in and around the Reed house, the result of the fight for Reed's Bridge was 102 rebel graves.11 Another one of Sarah's sons, Charles L. Reed, was a Confederate Captain who was killed on 30 November 1864 at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee. (Family lore holds that his brothers, Thomas and Monroe, who served in the same regiment, were present at his death but that was impossible because Thomas had been captured and paroled and then sent home in December 1863 and Monroe was in a prisoner-of-war camp in Illinois.12) According to family lore, Charles was too large for any available coffins and was buried on the battlefield, shrouded only in a blanket.13 His remains, along with those of 1,480 other soldiers, were afterward moved to the Georgia section of the Confederate Cemetery at Carnton, on the grounds of the John and Carrie McGavock Plantation at Franklin. Today, the burial ground is maintained by a private foundation. Capt. Charles L. Reed is buried in section 78, grave number 19.14The Confederate service records of Thomas Reed and Monroe Reed confirm that Union forces captured them both at Nashville, Tennessee on 16 December 1863. These records further confirm that Thomas took an oath of allegiance to the U.S. on 22 December 1963 and then was released, whereas Monroe apparently refused to do so and was afterward incarcerated in Camp Douglas, a federal prisoner-of-war camp in Illinois, until 20 June 1865, when he was finally released.15 Daniel O. Reed, who in 1862 enlisted in the same regiment and company as his brothers (Co. D, First Confederate Regiment of Georgia Volunteers), spent most of his time in the service at the hospital at Mobile, Alabama, where he suffered from some undisclosed malady. He was finally discharged, almost certainly for disability, on 16 February 1863 and from all appearances never again returned to active duty.16 At the conclusion of the Civil War, two of Sarah's sons, Mark Lowry and Daniel Reed, left Georgia and removed to Texas. (Daniel eventually moved to Arkansas.)17 Sarah Lowry Reed reportedly died in Catoosa County, probably at her own home, on 6 August 1870 at the age of 73. She was buried in an unmarked grave in the nearby Reed-Fowler Cemetery, which is today reportedly undistinguishable from the farmland around it except for some slight depressions in the ground.18 MARK LOWRY Mark Lowry was born 28 February 1821 in Jackson County, Georgia.19 He was reportedly the illegitimate son of Sarah Ann "Sally" Lowry and Jacob Reed (see preceding section regarding Sarah Ann Lowry). According to more than one source, Mark was also either named or nicknamed "Sam." His parents were eventually married "probably during the last half of [the] year 1828." As a consequence of his illegitimate status, Mark is said to have been the only one of the seven children growing up in Jacob and Sarah Ann's household who bore their mother's maiden name rather than their father's surname.20 The earliest public record we have of Mark Lowry reveals that by the time he reached adulthood he had removed to Walker County, Georgia, where he was married on 17 September 1845 to 21-year-old Elizabeth B. Murdock, who was two years younger than Mark.21 (Elizabeth was born 30 August 1824 in Walker County. Her father was Ellet or Elliott Murdock and her mother was Eliza Shannon Magill.22 See Murdock and Magill families.) During the seventeen years of their marriage, Mark and Elizabeth Lowry had eight children, each of which was almost certainly born in Walker County, Georgia:

Walker County, formed in 1833 from Murray County and located in far northwest Georgia, was originally much larger before it was reduced to its present 447 square miles by the formation of Dade (1837), Chattooga (1838), Catoosa (1853) and Whitfield (1859) counties. As some of its place names, such as Chickamauga, reveal, this area was originally the home of the Cherokee Indians before President Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 caused the native people to be forcibly removed to what is now the state of Oklahoma (originally called "Indian Territory"). The largest towns in Walker County were La Fayette, which was and still is the county seat, and Rossville, named for a famous Cherokee Indian chief.24 In 1855 one writer described Walker County as "a region of mountains, which generally run from N.E. to S.W. Their names are Taylor's Ridge, John's, Pigeon, Look-Out, and White Oak Mountains. The streams are East and West Chickamauga." (Most of these mountains are well over a thousand feet above sea level and some are more than two thousand.) This same observer also remarked that there were a number of natural springs in the county with the Medicinal Springs, owned by the Gordon family, being the best known. Two natural ponds, one with "no visible outlet," and a number of caverns, the "most remarkable" being Wilson's Cave, were chief among the county's other natural attractions.25

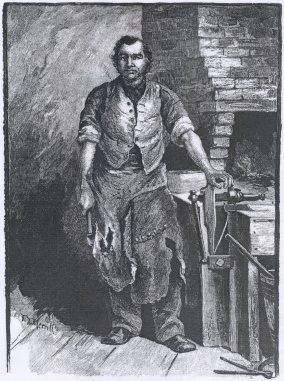

As one of only a few blacksmiths in this area, Mark Lowry was almost certainly kept busy. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, the South's plantation economy was in need of skilled artisans and tradesmen who we may suppose made a reasonably good living as a consequence, although many Southern plantation owners had blacksmiths of their own (oftentimes one of their skilled slaves).28 Although it is unlikely that Mark Lowry had anything at all to do with it, a story that was first published in 1843, "The Blacksmith of the Mountain Pass," is interesting to read for its insights into antebellum Southern culture.29 Considering the location, namely northern Georgia, and also the occupation of the title character, it is hard to imagine that this work of fiction was not brought to his notice. It is not unlikely that Mark Lowry was likewise familiar with Longfellow's popular poem, "The Village Blacksmith,"30 which celebrates this particular occupation. The 1860 federal census for Walker County, Georgia, conducted in late July and early August, found 35-year-old Mark Lowry (misspelled "Louery" in census indexes), living in the Chattanooga District of the county, in the vicinity of a small community identified by the census-taker as "Eagle Cleft" but more probably it was "Eagle Cliff" since it appears that there was never any place called "Eagle Cleft" in Walker County. The household included Mark's 34-year-old wife Elizabeth, 13-year-old daughter Mary Ann, 11-year-old Amanda Jane, 9-year-old son John, 4-year-old Charles, and a 1-year-old daughter identified as Jane, not Virginia Allis, which may also have been a mistake on the part of the census-taker. Martha Elizabeth and Sarah Josephine, who are not listed, had died in childhood (Martha on 5 April 1850 and Sarah on 16 January 1856 according to an undocumented source). Of course, James Francis was not yet born. It is interesting to note that for this census, Mark's occupation is given as "farmer" and another man who lives nearby, Duncan S. Evans, is now the local blacksmith. In this census, Mark is not listed among the county's slave owners.31 Eagle Cliff (not Eagle Cleft) was, and still is, located 7 miles southwest of Rossville and ten miles due south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, alongside the road (today's Georgia State Highway 193) between the towns of Flintstone and Frick's Gap. Situated on the west side of Chickamauga Creek, Eagle Cliff lies in the shadow of a tall mountain by the same name that either honors the memory of a Cherokee chief called Eagle or was so-named on account of the eagle aeries that reportedly abound in the rocky crags above.32 In 1860, this place was the focal point of a rural population of approximately 600 people spread out over two census enumeration districts-Mountain and Chattanooga. Of that number, 107 of the male heads of households in those districts were identified as farmers. There were also twelve widows (identified in the census by the letter "W") who almost certainly also lived on farms. Artisans and tradesmen were not very numerous: Only two blacksmiths, two carpenters, one cooper, one shoemaker, and one brick mason. There were also three teachers and a single physician, who must have had his hands full tending to the medical needs of such a large and spread-out population during an era when there were no paved roads, travel was by horseback or horse-drawn vehicle, and doctors routinely made house calls.32 On 26 November 1860 Mark and Elizabeth Lowry lost a third child, Virginia Allis (or Jane as she is identified in the 1860 census). The cause of death and place of burial are unknown.34 Although there were reportedly a great many pro-Union people living in this region of Georgia on the eve of the Civil War,35 Mark Lowry was apparently not one of them. In the summer of 1861, after the war began, he bid goodbye to his wife and children and traveled to Knoxville, Tennessee, where on 8 July 1861 he enlisted for one year's service as a Private in Company G, 26th Tennessee Volunteers (a.k.a. 3rd East Tennessee Volunteers), which in late 1862 was re-designated the First Regiment of Confederate Infantry (Georgia Volunteers).36 Family lore holds that one of Mark Lowry's half-brothers, James J. Reed, enlisted at the same time and place in the same regiment but according to James' service record, he (along with his four brothers) joined up in 1862, at which time they were assigned to Company D.37 Although Mark Lowry's term of military service was relatively brief (a total of sixteen months), it was nonetheless eventful. The Military Annals of Tennessee reports, "In July and August 1861 the companies composing the Twenty-sixth Regiment rendezvoused at Knoxville and were there mustered into service." Following the capture of the city of Bowling Green, Kentucky on September 18, 1861 by 4,000 Confederate troops under the command of Gen. Simon Boliver Buckner, "the regiment was ordered from Knoxville to Bowling Green."38 There, on October 8, 1861, Mark Lowry was sent on detached duty to one of a number Confederate army hospital located in the vicinity of Bowling Green, presumably serving as a nurse or hospital orderly. Another card in Lowry's service file states that he was sent on detached duty to a hospital in Nashville, Tennessee but this is probably an error since there is no doubt that the regiment was ordered to Bowling Green (unless he was sent on detached service at Nashville before his regiment was ordered to go to Kentucky).39 In January 1862, Lowry's regiment next "received orders to go to Russellville, Ky., and remained there until ordered to Fort Donelson, which was about the 10th of February 1862." After boarding "the steamer 'John A. Fisher,'" at Cumberland City, on "the night of February 13th," the 26th Tennessee "reached Fort Donelson just before daylight the 14th, and was at once placed in the line of battle."40 According to The Military Annals of Tennessee, the 26th Tennessee regiment "gallantly" did "its duty in this ever-memorable battle, under command of the brave and heroic Col. Lillard, assisted by as brave and true officers as ever went to battle."41 On 16 February 1861 General Buckner surrendered Fort Donelson to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. However, Lowry's service record states that his name "appears on a muster roll of a detachment of the 26th Tennessee, which escaped from Fort Donelson."42 He was fortunate. Most of Lowry's fellow privates were taken captive, incarcerated for several months in a federal prisoner-of-war camp in Indiana, and finally exchanged at Vicksburg, Mississippi in September 1862.43 Mark Lowry's whereabouts during the eight months that followed his escape from Fort Donelson are uncertain but we do know that he was discharged from the Confederate army on November 6, 1862, by order of General Sam Jones.44 Because his service record does not specify any particular reason, we may reasonably assume that it was simply due to expiration of enlistment. Some researchers who have also done some work on this line seem to have confused Mark Lowry with one of three other men bearing that name that served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. One, who was attached to the First Battalion of Tennessee Volunteers (Colm's Battalion), died during the war. The other two were commissioned officers: Brigadier General Mark P. Lowry of Mississippi; and Capt. Mark Lowry of Co. A, 25th Tennessee Infantry, who was present at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863. 45 Sadly, during the several months that our Mark Lowry was away in the service, his son James Francis, who was born 11 December 1861 and whom the absent soldier never saw, died on either 5 January 1862. The fact that Mark's wife Elizabeth also died shortly thereafter, on 30 January 1862 at the age of thirty-eight, 46 suggests that her death was due to some sort of complication connected with childbirth. Although mother and baby were almost certainly buried together somewhere in Walker County, Georgia, the location of their graves seems to have been lost to history. Nor do we know who looked after Mark's children until he was discharged from the service and returned home. About a year-and-a-half after Elizabeth's untimely demise, Mark Lowry remarried. His second wife was Amanda Louise Drummond. Born 29 November 1844 in either Tennessee or Alabama, Amanda was only nineteen when she and Mark were married on 23 July 1863 in Polk County, Georgia (two counties south of Walker). Mark was forty-three. 47 Over the next several years, Mark and Amanda had the following children together:

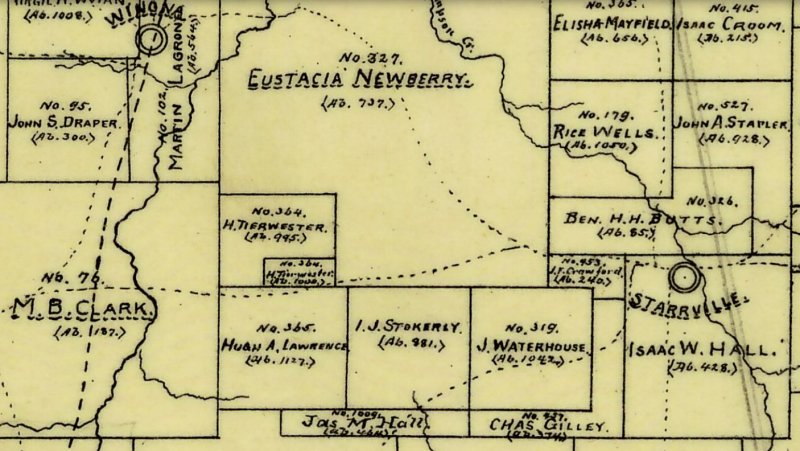

During the Civil War, the Confederate government kept records of the amounts it paid to private citizens for goods or services. These records are preserved today by the National Archives in Washington, D.C. One of these files, which are alphabetically organized by surname, concerns Mark Lowry or as it spelled in the records, "Lowrey." Among the several papers in this file is a claim dated 8 March 1862, in the amount of $100 "for service of [a] four horse wagon and team for use of Col. Whittaker [of the] Ark. Regt." Another voucher, in the amount of $110, is for 500 bundles of fodder and 44 bushels of corn, plus a fee for hauling. The recipient signed it on 29 December 1862 at Sparta, Tennessee. A third voucher payment of $15 was for "use of smith & shop for three days." A fourth records the payment of $113 on 24 August 1863 for the "use of shop and tools" at $3 per day for 36 days, plus $3 for "making three lb. horse shoe nails" and $2 for wagon repairs. A fifth document, dated 11 December 1863, at Rogersville, Tennessee, is a receipt for $88 from the Confederate Commissary of Subsistence, in payment for 22 bushels of wheat.49 Although it is difficult to know with certainty that any or all of these transactions involved my ancestor (owing to the fact that there was more than one man named Mark Lowry living in the Confederacy at the time), the payments for blacksmith work and the use of shop and tools certainly seem to fit our Mark Lowry. In point of fact, the only questionable receipt in the file is the one dated 8 March 1862, when Private Lowry was still serving in the Confederate army, after escaping from Fort Donelson. This claim and perhaps also the one for fodder and corn may have involved a different Mark Lowry.50 In September 1863, no doubt to the dismay of Mark Lowry and his neighbors in Walker County, the Civil War almost literally came to their doorsteps when Confederate troops under the command of General Braxton Bragg evacuated nearby Chattanooga in the face of an advancing federal army commanded by General William Rosecrans. (In some cases, such as Mark's mother and father, who lived in neighboring Catoosa County, it reached their actual homes.) As Bragg and thousands of Confederate soldiers came rushing down into Georgia, skirmishes between these troops and pursuing federal soldiers began to take place, culminating on 19 and 20 September in the bloody Battle of Chickamauga (a Confederate victory that nullified shortly afterward by the arrival of Ulysses S. Grant, who took over from Rosecrans and eventually defeated Bragg in the Battle of Lookout Mountain.) Not surprisingly, this clash of armies forced many of the farm families of northwest Walker County to flee to safety elsewhere. It is also not too surprising therefore, that when the Georgia militia was re-organized in 1864 Mark Lowry was listed as a resident of neighboring Bartow County (just to the south of Walker), where, incidentally, he was exempted from any further military duty on account of his discharge from earlier service. 51 When the Civil War concluded, the Lowry family packed up their belongings and went west, probably in a covered wagon. At the end of their 700-mile journey, which took them across Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana (and possibly also Arkansas), they reached Starrville, a small but thriving community located a few miles north of Tyler, Texas-the seat of Smith County-in a region where the thick stands of tall pine trees almost certainly reminded them of their former home in Georgia (except that there were no mountains!). The year of their move is uncertain. One source indicates that Mark and Amanda's first child, Lula, was born in Georgia; other says Texas. Whatever the case, there is little doubt that they made the journey sometime in 1865 or 1866.52 The reason for the Mark Lowry family's move to Texas is not very hard to guess: Georgia, and particularly the once-peaceful valley from which they had been forced to escape in the face of battle, was a scene of destruction whereas Texas had been almost entirely untouched by the great national conflict. From all appearances, Mark Lowry chose to settle in Smith County because it was already the home of at least one probable cousin who almost certainly encouraged him in that decision. This cousin's name was Francis Lawson Lowry, who was a son of Mark's Uncle David Lowry. Another possible cousin living in Smith County at this time was Isaac Pierce Lowry, son of a James Lowry, who may or may not have also been one of Mark's uncles.53 David Lowry, Mark's probable uncle, was married in Jackson County, Georgia, the same county in which Mark Lowry was born. David, who joined his son Francis in Texas in his old age, is also buried in the same cemetery in Starrville as Mark Lowry.54 Not surprisingly, when Mark and Amanda Lowry made the journey to Texas, all of Mark's living children came with them. These were: Mary Ann, Amanda Jane, John Elliot, Sarah Josephine, Charles Monroe-and Lula too, if she was born in Georgia rather than in Texas.55 In April 1868 Mark Lowry purchased a little more than four acres of land "in the town of Starrville fronting the Dallas road" for $100 from C.J. Chaney, Eli Chaney, and James and Elizabeth Dyer. Owing to an act of the Texas legislature that forbade both liquor and gambling within one mile of the Starrville Female Academy, a clause in the deed ordered him to refrain from selling any "ardent spirits" or "fermented liquors" on the premises. Gambling was also forbidden.56 This document was not unique; every deed for land in the town of Starrville contained the same clause.57 Mark almost certainly built or had a house built for his family on this property. In a book in the Tyler, Texas Public Library, there is a map of Starrville in the 1870s (apparently redrawn from some original map), showing a small piece of property identified only by the surname Lowry, which was located about a block east of the town square and on the south side of the Dallas Road.58 This is almost certainly the property described in the deed described in the preceding paragraph.

In its heyday, which was from 1852 to 1907, Starrville was a small but thriving East Texas community. Today, apart from a scattered handful of private residences, Starrville is a ghost town where the former inhabitants now lie buried in the town cemetery that is situated a little to the south of the former town site. A Texas Historical Commission marker, erected in 1977 alongside FM 16 tells its story:

Between 1869 and 1871, two of Mark's daughters were married at Starrville. The first was Mary Ann, who married Morris Ward, Jr., a young Confederate veteran, on 16 September 1869. (Mary Ann and Morris are my great great grandparents.) The second was Amanda Jane, who married John W. King, on 23 March 1871.62 In 1870 Amanda Lowry gave birth to a daughter, Helen Gertrude, who was married eighteen years later to John W. Bryant and afterward went to live in Hill County, later in Dallas.63 In 1889 Mark Lowry and a man named William D. Lowry (who was probably a relative of some sort but whose relationship to Mark I have so far been unable to determine) jointly purchased two acres of land in Starrville, presumably for some business purpose. What became of it is unknown. 64 Sometime during the 1890s, Mark and his wife Amanda moved to neighboring Upshur County, where he passed away on 30 April 1897 at the age of 76. He was buried in Starrville Cemetery (see photo immediately below).65 Sometime after her husband's death, Amanda Drummond Lowry returned to Georgia, where she died on 29 October 1899 in Bartow County. She is buried at Euharlee Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Bartow County. 66

MARY ANN LOWRY (1846-1880) Mary Ann Lowry, the eldest child and daughter of Mark Lowry and his wife Elizabeth Murdock Lowry, was born 14 March 1846 in Walker County, Georgia.67 When she was about twenty years old, she came to Texas with her father and stepmother and several siblings (see preceding section about Mark Lowry). The family settled at Starrville in Smith County. Mary Ann Lowry married Morris "Doc" Ward Jr., a young Confederate veteran, at Starrville on 16 September 1869. 68 They made their home in neighboring Upshur County and together they had the following children:

Mary Ann Lowry Ward died at Big Sandy, Upshur County, Texas on 16 Jan 1880 at the age of only thirty-four. 70 The cause of her death is unknown. She was buried at Chilton Cemetery in Big Sandy, Texas but there does not appear to be a marker on her grave. Her husband eventually remarried (see Ward family) and had one more child. NOTES 1 Georgia Lowrey Families [http:lowreys.net.georgialowreys/familyfiles/fam000222.html; accessed 15 September 2001]; Charles Lowry Sr. [http://trees.ancsstry.com/tree/13916670/person/17934196; accessed 8 June 2010]. 2 Ibid. 3 I have looked at the Jackson County, Georgia marriage record book for 1828 and there is no record of this marriage therein. 4 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]; undated, unsigned, undocumented Reed family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 5 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]. 6 U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Population, Catoosa County, Georgia and Ninth Census of the United States, 1870; Population, Catoosa County, Georgia. 7 Jos. M. Brown, Mountain Campaigns of Georgia (Buffalo, New York: The Matthews-Northup Co., 1895), 13-16. 8 Ibid. 9 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]. 10 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file of James J. Reed. 11 Charles E. Belknap, History of the Michigan Organizations at Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Missionary Ridge, 1863 (Lansing, Michigan: Robert Smith Printing Company, 1897), 96. 12 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service files of Charles L. Reed, Thomas N. Reed, and Monroe Reed.13 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]. 14 Williamson County, TN, Cemeteries, McGavock Confederate Cemetery [http://files.usgwarchives.net/tn/Williamson/cemeteries/mcgavock.txt; accessed 10 June 2010]. 15 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service files of Thomas N. Reed and Monroe Reed. 16 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file of Daniel O. Reed. 17 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]. 18 Ibid. 19 Grave marker, Starrville Cemetery, Smith County, Texas. 20 Reed, Descendants of Jacob Reed [http://www.angelfire.com/ga4/jholc/Reed.html; accessed 8 June 2010]; undated, unsigned, undocumented family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 21Undated, unsigned photocopy of the John W. King family Bible records, sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. (John W. King married into the Lowry family.) I have tried to obtain an official record of this marriage but Walker County, Georgia does not have any extant marriage records before the 1880s. 22Undated, unsigned photocopy of an Elliott or Ellet Murdock family record sheet, sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. (John W. King married into the Lowry family.) 23Undated, unsigned photocopy of the John W. King family Bible records, sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. (John W. King married into the Lowry family.) 24George White, Historical Collections of Georgia, Third Edition (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1855), 667-9. 25Ibid. 26U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Population, Walker County, Georgia. 27U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Slaves, Walker County, Georgia. 28"Antebellum Artisans," The New Georgia Encyclopedia [http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-609&hl=y ; accessed 10 June 10, 2010]. 29 John Basil Lamar, "The Blacksmith of the Mountain Pass," Library of Southern Literature, volume 14, compiled by C. Alphonso Smith,. (Atlanta, Georgia: The Martin and Hoyt Company, 1907 & 1910), 6308-17. 30 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Village Blacksmith (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1890). 31 U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Population, Walker County, Georgia. 32 Kenneth K. Krakow, Georgia Place Names (Macon, Georgia: Winship Press, 1975), 68. 33 U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Population, Walker County, Georgia. 34 Undated, unsigned, undocumented Lowry family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 35 "Walker County," The New Georgia Encyclopedia [http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2407&hl=y ; accessed 10 June 10, 2010]. 36 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file for Mark Lowry. 37 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service files of James J. Reed, Charles L. Reed, Thomas N. Reed, Daniel Reed, and Monroe Reed. 38 John Berrien Lindsley, ed., The Military Annals of Tennessee (Nashville: J.M. Lindsey & Co., 1886), 410-11. 39 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file for Mark Lowry. 40 Lindsey, 411. 41 Ibid. 42 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file for Mark Lowry. 43 Lindsey, 412. 44 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file for Mark Lowry. 45 National Archives & Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Civil War Service file for Mark Lowry (of the First Battalion of Tennessee Volunteers); The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi (n. p., 1908), 947; United States War Dept., Robert N. Scott, ed., The War of the Rebellion, A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume XXX (in four parts), Part II-Reports (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1890), 541. 46 Undated, unsigned, undocumented Lowry family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 47 Ibid. 48 Ibid.; Polk County, Georgia Marriage Book A-B (1852-1885), 271. 49 National Archives & Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Confederate Citizens file for Mark Lowry and Mark Lowrey. 50 Ibid. 51 Nancy J. Cornell, compiler, 1840 Census for Re-organizing the Georgia Militia (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2000), 25. 52 U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States, 1870: Population, Smith County, Texas, Starrville Post Office, page 70. 53 U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Population, Smith County, Texas, Starrville Post Office, pages 102 & 110; Andrew L. Leath, compiler, Abstracts of the Smith County Probate Records, Smith County, Texas, 1846-1880 (Tyler, Texas: Smith County Historical Society, 1984), 137. 54 Grave marker of David Lowry, Starrville Cemetery, Smith County, Texas. 55 Undated, unsigned, undocumented Lowry family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 56 C. J. Chaney, Eli Chaney, and James and Elizabeth Dyer to Mark Lowry, deed for four acres of land "in the town of Starrville fronting the Dallas road," April 1868, Book Q, p. 110, Smith County Courthouse, Tyler, Texas. 57 Chronicles of Smith County, Texas, vol. 23, no. 1, Summer 1984, 10. 58 Ibid., 11. 59 Ibid., 27. 60 Henry S. Cobb to Mark Lowry, deed for "a certain lot of land in the town of Starrville whereon there is a Blacksmith Shop now occupied by said Mark Lowry," dated September 8, 1870, Smith County Courthouse, Tyler, Texas, Book Q, p. 119. 61 Texas State Historical Commission marker, Starrville, Texas. 62 Marriage record, Morris Ward Jr. to Mary Ann Lowry, Book F, p. 25, Smith County Courthouse, Tyler, Texas; Marriage record, John W. King to A. J. (Amanda Jane) Lowry, Book ?, p. ?, Smith County Courthouse, Tyler, Texas. 63 "Mrs. H. Bryant Services Set," Dallas Morning News, April 2, 1940. 64 Lula A. Wallace to W. D. Lowry and Mark Lowry, deed for "two acres of land situated in Smith County, Texas," dated January 15, 1889. Book 39, pp. 338-40, Smith County Courthouse, Tyler, Texas. 65 Mark Lowry grave marker, Starrville Cemetery, Smith County, Texas; seen and photographed by the author. 66 Charles Brightwell to Steven Butler, email dated February 5. 2003. 67 Undated, unsigned, undocumented Lowry family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 68 Marriage record, Morris Ward Jr. to Mary Ann Lowry, Book F, p. 25, Smith County Courthouse, Tyler, Texas. 69 Undated, unsigned, undocumented Lowry family record sheet sent to my Aunt Inez Jenkins Hickman by an unknown relative in the 1970s. 70 Ibid.

This website copyright © 1996-2021 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |

Another map in the same book shows a blacksmith shop located on the northeast corner of present-day FM (Farm-to-Market Road) 16 (originally known as the Dallas-Shreveport Road), which runs east-west and County Road 363, which runs north-south.

Another map in the same book shows a blacksmith shop located on the northeast corner of present-day FM (Farm-to-Market Road) 16 (originally known as the Dallas-Shreveport Road), which runs east-west and County Road 363, which runs north-south.