|

The West Family

By Steven R. Butler, Ph.D.

Introduction

Charles West |

Jeremiah West |

William R. West

Introduction

The Butler and West families are related by virtue of the marriage of my grandfather, Herman Hardin Butler, to my grandmother, Alice Mae Tate, who was the daughter of Isaac Henry Tate and his step-sister/wife Sarah Augusta West, who was the daughter of William R. West of Georgia and his wife Mary Caroline Strahan (who became Isaac H. Tate's stepmother when she married Isaac's widowed father, Harrison Tate in 1861).

The precise origin of our branch of the West family is presently unknown but it is very likely that they were English colonists who came to America in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. The story of our branch begins in Maryland, from where they removed to Georgia at a moment in history when the old Antebellum South was being formed.

Charles West (1770-1860)

Our earliest known ancestor in this line is Charles West, who was born a British subject in Dorchester County, Maryland on 3 October 1770.1 The identity of his parents is unknown. Likewise, nothing is known about his childhood.

By the time that Charles West reached his majority, the United States had won its independence. On 9 January 1791, when George Washington was President and in the same year that the Bill of Rights was adopted, Charles West, age twenty-one, married eighteen-year-old Sarah Haynes, who was also a native of Dorchester County, Maryland,2 although it appears they were married elsewhere as their names are not listed in the marriage records of Dorchester County for this time period.

There is some uncertainty regarding the number of children this couple had. The following named sons, nine altogether, have been confirmed by documentary evidence: Eli; Jeremiah (born about 1795 in Georgia); Charles Jr.; John; Levin (born about 1801 in Georgia); Tillman D. (born about 1816 in Washington County, Georgia); James K.; Andrew; and Jesse. The following three daughters have likewise been confirmed by documentary evidence: Mary (wife of Newton Lynn); Ann (wife of Henry Key); and Rhoda (married name, Waaden).3

Sometime during the first two decades of their marriage, but certainly no later than 1816 (when their son Tillman was born), Charles and Sarah West moved to Washington County, Georgia, where they were enumerated in the 1820 federal census. Unfortunately, it is difficult to ascertain where they resided prior to that time. They cannot be found in either the 1800 or 1810 federal census of Maryland4 and unhappily, the federal census records for Georgia, for both 1800 and 1810, were destroyed when the British burned Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812.

When the 1820 federal census for Washington County, Georgia was taken on August 7, the Charles West household consisted of two free white males less than 10 years of age (born between 1810 and 1820), three free white males ages 10 to 16 (born between 1804 and 1810), one free white male aged 16 to 26 (born between 1794 and 1804), one free white male over 45 (Charles), one free white female under 10 (born between 1810 and 1820), one free white female between 10 and 16 (born between 1804 and 1810), one free white female between 16 and 26 ( born between 1794 and 1804), and one free white female over 45 (Sarah), for a total of nine free white people, seven of who were obviously Charles and Sarah's children.5

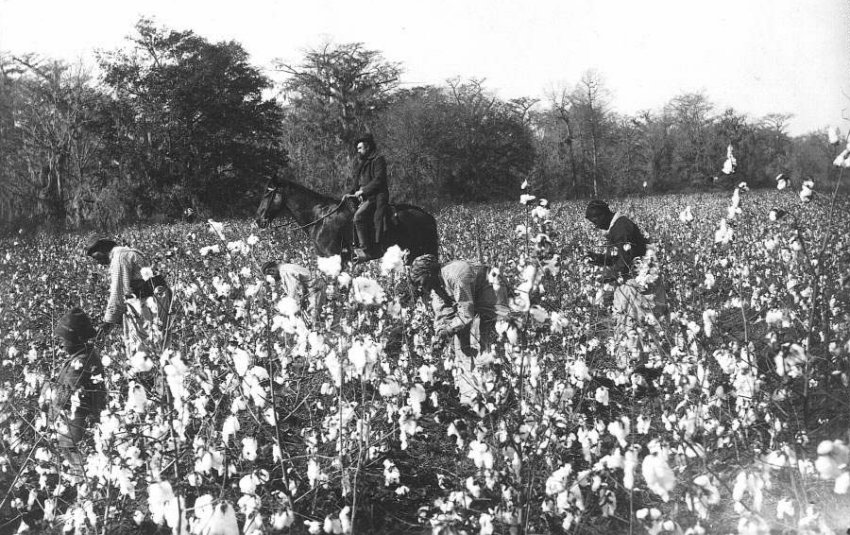

In 1793--two years after Charles and Sarah West were married--an ingenious Connecticut Yankee named Eli Whitney, while visiting a planter friend in Chatham County, Georgia (near Savannah), invented a remarkable machine that quickly separated cottonseeds from the fiber that surrounded them. In practically no time at all this new technology led thousands of Americans living in the southern states and territories to plant short staple cotton, which prior to the invention of the so-called "cotton gin," was difficult to grow profitably owing to the long time it took to separate the seeds from the fiber by hand. Tragically, the invention of the cotton gin also resulted in the spread of slavery from the original eastern seaboard states to the new states west of the Appalachian Mountains such as Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, as well as parts of existing states such as Georgia, that were either unsettled or only lightly settled. It is not too surprising therefore, in view of the time and place in which he lived, that the 1820 census also reveals that Charles West owned thirteen slaves (5 males and 8 females),6 which also informs us that although he was yet not a member of the large planter class, which was defined by the ownership of twenty or more slaves, he was well on his way to achieving that dubious status.

Washington County, where Charles West and his family lived in 1820, was named for General George Washington. It was formed in 1784-five years before the Revolutionary War hero became the first President of the United States under the Constitution. Sandersville, the county seat, was (and still is) located about 128 miles southeast of Atlanta. The rise of cotton cultivation was almost certainly the driving force behind the county's rapid population increase, from 4,552 in 1790 to nearly 11,000 by 1820. Nearly forty percent of that number were enslaved African-Americans.7

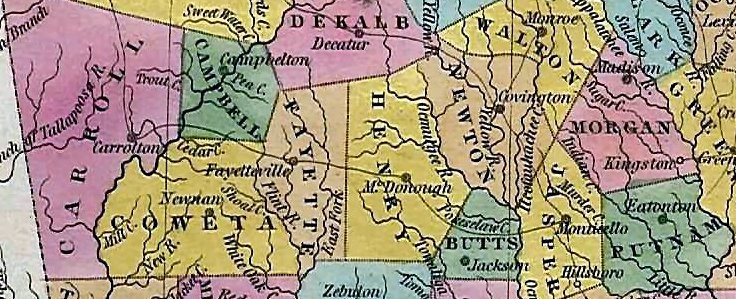

Central Georgia in 1823; Washington County is to the right. Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to learn the extent of Charles West's landholdings or any of his public acts due to the fact that in 1864, during General William Tecumseh Sherman's celebrated (or infamous, depending upon one's viewpoint) "March to the Sea," Union troops burned the Washington County courthouse and almost all the records it contained.

Sometime between 1820 and 1830, Charles West and his family removed to Henry County, Georgia, which is located in the north central section of Georgia, about 31 miles southeast of Atlanta and 100 miles from Washington County. In 1830 the federal census revealed that the Charles West household consisted of one free white male between 10 and 15, one free white male between 15 and 20, three free white males between 20 and 30, one free white male between 50 and 60 (Charles), and one free white female between 50 and 60 (Sarah). None of Charles West's three daughters are listed because they were almost certainly all married by this time and living with their husbands and their own children, if any. The 1830 census also reveals that Charles West had achieved the status of a large planter by his ownership of twenty-nine slaves (16 males and 13 females).8

Slaves picking cotton in the antebellum South. Source unknown.

Ten years later, the 1840 federal census taker for Henry County found the Charles West household with one free white male age 15 to 20 (probably Tillman D.), one free white male age 70-80 (Charles, who was exactly 70 that year), one free white female between 60 and 70 (Sarah), and twenty-five slaves (12 males and 13 females).9

There are five land transactions involving Charles West on file in the Henry County, Georgia courthouse deed records. Here is a list:

- November 16, 1827: John Brooks of Henry County, to Charles West of Washington County, for $1,650, lot 37 and part of lot 38 in the 11th District of Henry County, on the south side of the north prong of the Cotton River. Wit: James Henry and George West. Recorded in Henry County, Georgia Deed Book A, p.561 on July 9, 1828.

- January 28, 1828: James Henry to Charles West, for $1,000, lot 27 in the 11th District of Henry County, containing 202½ acres. Wit: Silas Mosley and Thomas D. Johnson. Recorded in Henry County, Georgia Deed Book B, p.431 on January 31, 1828.

- May 6, 1828: Charles West to son-in-law Henry A. Key of Jasper County, a seven-year-old negro girl, named Caroline, for "affection and esteem." Wit: James Love and Thomas D. Johnson. Recorded in Henry County, Georgia Deed Book F, p.50 on February 7, 1832.

- October 9, 1828: Alexander Moore to Charles West, for $1,800, lot 28 in the 11th District of Henry County, containing 202½ acres. Wit: William Hardin and Thomas D. Johnson. Recorded in Henry County, Georgia Deed Book A, p.615 on October 10, 1828.

- December 19, 1835: Silas Mosley to Charles West, for $300, part of lot 40 in the 11th District, containing 50 acres. Wit: Nathaniel Carrill and Tillman D. West. Recorded in Henry County, Georgia Deed Book H, pp.95-6 on November 2, 1836.

Interestingly, there seems to be no record of Charles West selling any of this Henry County property.

North Central Georgia in 1831, showing Henry and Jasper counties. Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Sometime shortly after the 1840 federal census was taken, Charles West and his wife Sarah moved to Muscogee County, Georgia, where they acquired a plantation situated a few miles east of Columbus, the county seat. This property is today known as "Westmoreland," which may be the name that Charles gave it. His son Tillman, with whom Charles West seems to have enjoyed a much closer relationship than with his other children, also moved to Muscogee County. Sarah West did not live very long after the move. She died on 20 December 1840 and was buried in a small graveyard on the property,10 which is located today on the south side of Warm Springs Road, near the small town of Midland, Georgia.

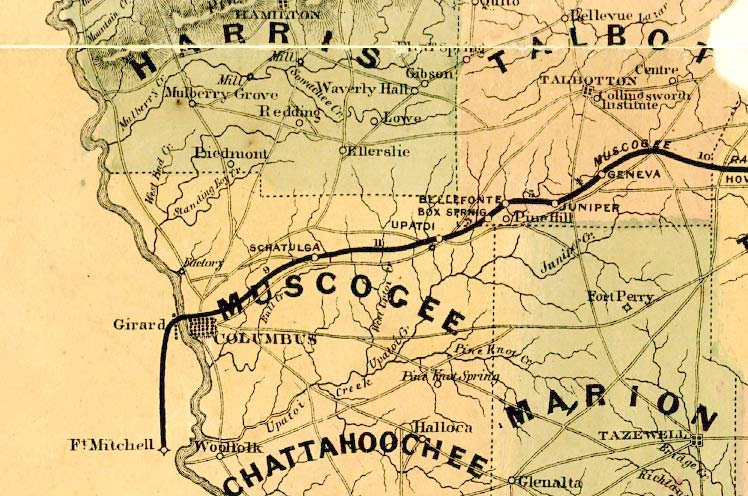

Muscogee County, located in west-central Georgia, was named for the Muscogee Creek Indians that originally inhabited the area. It was established in 1826 after the Creeks agreed to a treaty in which they ceded a large tract of territory adjacent to the Chattahoochee River, which forms the boundary between Georgia and Alabama. Columbus, the seat of Muscogee County, was founded in 1828.

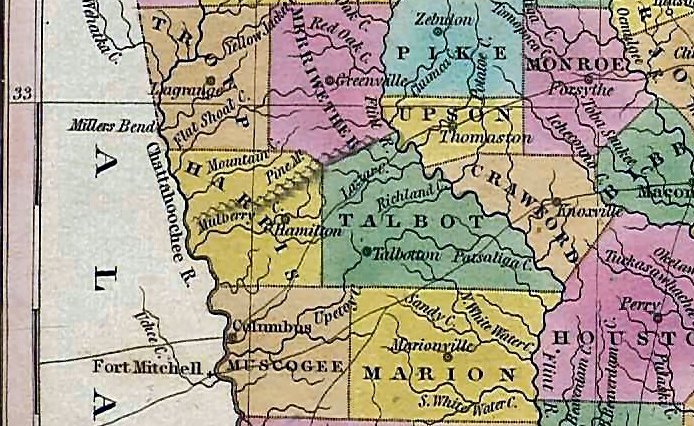

North Georgia in 1831, showing Muscogee and surrounding counties. Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

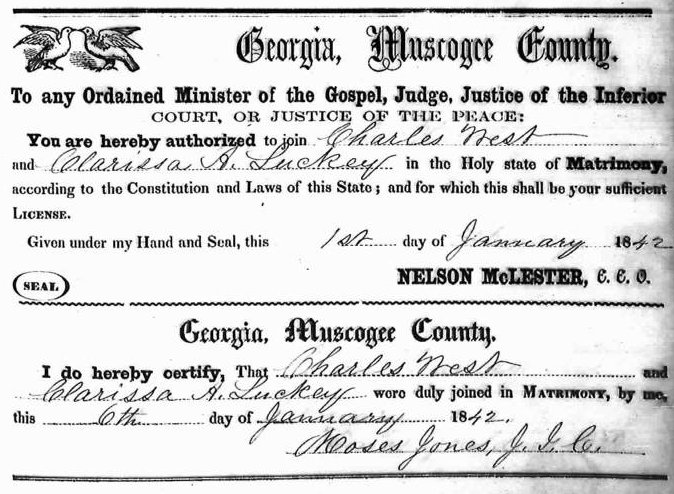

Although Charles West was seventy years old when his wife Sarah died, he remarried a little more than a year later, on 6 January 1842. His second wife, Clarissa A. Luckey, was a fifty-one year old native of Wilkes County, Georgia who may have been a widow.11 In 1850, they were enumerated together in the federal census for Muscogee County, Georgia.12 The 1850 census also reveals that Charles owned twenty-three slaves at this time-12 males and 11 females-as well as $11,400 worth of real estate, which in 1850 was a very considerable sum of money.13

Marriage record of Charles West and Clarissa Luckey. Courtesy Georgia State Archives, Atlanta, Georgia.

There are five land transactions involving Charles West on file in the Muscogee County, Georgia courthouse deed records. Here is a list:

- July 4, 1840: Eli B. Spivey to Charles West, for $10,600, a total of 1,007 acres of land in adjoining lots in Districts 9 and 18, where West built his home, "Westmoreland," still standing today. Recorded June 9, 1841 in Muscogee County, Georgia Deed Book B, p.210.

- December 17, 1842: Daniel Huff to Charles West, for $1,035, south half of lot 43 and part of lot 42 in 18th District, adjoining the land that West bought from Spivey in 1840. Recorded October 3, 1843 in Muscogee County, Georgia Deed Book C, pp.101-2.

- February 9, 1844: Daniel Huff to Charles West, for $3,000, most of lots 66 & 67 in 9th District, adjoining land (to the south) purchased from Spivey in 1840. Recorded February 10, 1844 in Muscogee County, Georgia Deed Book C, p.161.

- June 1, 1844: Charles West to son, Tillman D. West, for $2,870, the land purchased from Huff in item no. 3 above. Recorded September 11, 1844 in Muscogee County, Georgia Deed Book C, p.261.

- June 6, 1849: James H. Edmundson of Harris County, Georgia, to Charles West, for $1 and in exchange for two promissory notes from Edmundson to West, lot 43 in the 9th District of Muscogee County. Recorded July 15, 1856.

There are also four land transactions involving Charles West on file in the Harris County, Georgia courthouse deed records. Here is a list:

- March 7, 1831: To Charles West, for $400, as highest bidder for lot 58 in the 18th District of Muscogee County, consisting of 202½ acres, per court order of the sale of the estate of John Brantley, deceased. Wit: P. T. Bedelet (or Redelet) and A. F. Gordon. Recorded in Harris County, Georgia Deed Book A, p.613 on July 7, 1831.

- December 2, 1840: Horace M. Jenkins to Charles West, for $1,100, two-thirds of lot 71 of the 18th District of Harris County, formerly Muscogee County. Wit: James Fincher and Tillman D. West. Recorded in Harris County, Georgia Deed Book D, p.159 on February 16, 1842.

- December 15, 1841: John Patterson to Charles West, for $540, one-third of lot 71 of the 18th District of Harris County, formerly Muscogee County, containing 67½ acres. Wit: T. D. West and John F. Boyd. Recorded in Harris County, Georgia Deed Book D, p.160 on March 2, 1842.

- October 17, 1842. Charles West to Leven West, for $500, lot 71 of the 18th District of Harris County, formerly Muscogee County. Wit: Rolin W. Smith, Tillman D. West and David Huff. Recorded in Harris County, Georgia Deed Book D, p.239 on [date not given].

In 1853, Charles West had a small but comfortable one story frame house built on his property, facing the road to Warm Springs. It is still standing today.14 The center of the front of the house features four white Ionic columns supporting a classical triangular pediment, with two staircases on either side of the elevated front porch. Two tall brick chimneys stand above the roof on either side. One researcher has identified this structure as a stagecoach stop/tavern where both the French General Lafayette and Jenny Lind, the so-called "Swedish Nightingale," once stayed but this claim is dubious. For a start, the building looks very much like a typical plantation house of the region, not a tavern. Secondly, although General Lafayette, the famous Revolutionary War hero, did indeed pass through this region during his tour of the United States, he did so in 1825, which was more than a quarter of a century before the house was built. It is doubtful too that Jenny Lind, who toured the United States from 1850 to 1852, stayed there as there seems to be no evidence that she ever performed anywhere in Georgia.

"Westmoreland," the home of Charles West and second wife Clarissa. Author photo.

Charles West and his second wife lived in this house for six years, until she passed away on 26 January 1859 and was buried beside his first wife, Sarah, in the little graveyard nearby.15 Following Clarissa's death, Charles West went to live with his son Tillman and family, with whom the ninety-year-old planter was enumerated in the 1860 federal census for Muscogee County, Georgia.16 In February 1860, he made his will, a three-page document in which ahead of his actual demise he gave several large cash bequests to children and grandchildren and slaves to others-thirty-three in total. Consequently, by the time that the federal census was taken, the number of slaves he still possessed was down to five. Charles' son Tillman now owned thirty-two, seven of who were originally the property of his father.17 On 6 July 1860, not long after the census was taken, Charles died and he too was buried in the little cemetery nearby his house, between his two wives.18 On 10 July 1860 his death was announced in the Columbus Enquirer.19

The graves of Charles West and both wives at "Westmoreland." Author photo.

Although, as pointed out above, Lafayette never stayed at Westmoreland nor is it very likely that Jenny Lind ever visited there either, another famous person may actually have some association with the place. A Georgia state historical marker, erected in 1954 alongside Warm Springs Road, adjacent to Westmoreland, explains:

"BLIND TOM"

200 feet east is the grave of Thomas Wiggins (1843-1908). As "Blind Tom," he thrilled audiences here and in Europe with his remarkable musical performances. Born a slave, his native genius led him reproduce perfectly on the piano any sound he heard, including musical compositions and the songs of birds. His owners, the Bethune family, discovered this rich gift when they heard exquisite music in their home near Columbus and found the little black boy at the piano. He reached the zenith of his fame on European tours during which he played before royalty.

Unfortunately, even Westmoreland's association with "Blind Tom" Wiggins is questionable. When Wiggins died in 1908 in Hoboken, New Jersey, while on tour in the North, he was buried in Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, where in 2002 a handsome marker was erected on the site of his burial. It is believed however, that Fannie Bethune, the youngest surviving member of the family that originally owned Tom as a slave and initially promoted his talent, had his body removed from Evergreens twenty years after his death and taken back to Georgia, where he was purportedly reburied at Westmoreland plantation. Although there is unfortunately no evidence to support this claim, Georgians have chosen to believe it and in 1976, an engraved granite marker was placed on the site of Tom's alleged grave,20 which had previously been marked with only a large stone.

Jeremiah West (1796-1851)

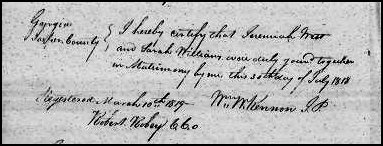

Jeremiah West, the second oldest son of Charles West and his wife Sarah, was born 6 January 1796 in Georgia,21 possibly in Washington County, where he was almost certainly raised. On 30 July 1818, at the age of twenty-two, he was married in Jasper County, Georgia to twenty-seven-year-old Sarah Williams, a native of Virginia.

Marriage record of Jeremiah West and Sarah Williams. Courtesy Georgia State Archives, Atlanta, Georgia.

This couple reportedly had a son named Elijah Hudson West, who was born in 1825 but this claim appears to be a researcher's mistake. Census records for this period indicate that Jeremiah and Sarah had only one son, whose name was William R. West, and that he was born in Georgia (in either Jasper or Henry County) in 1828. Elijah Hudson West was a real person but Jeremiah and Sarah West were almost certainly not his parents. Jeremiah and Sarah also reportedly had a daughter named Sarah A. West, who is supposed to have been born on 14 February 1823. This could be true. Federal census records confirm that Jeremiah and Sarah West had two daughters, both of whom were born between 1820 and 1825. Unfortunately, the only census in which they were enumerated in the Jeremiah West household (1830) does not give their names, which means they either predeceased their parents or were married and living with their husbands by 1840.

In 1820, the Jeremiah West family was enumerated in the federal census for Jasper County, Georgia as follows: one free white male age 16 to 18; one free white male age 16 to 25; one free white male age 26 through 44 (presumably Jeremiah); and one free white female age 26 through 44 (Sarah).22 A brother, John West, who was married in Jasper County in 1811, was likewise enumerated in this census.

Jeremiah West had no slaves in 1820. Whether this was a conscious choice or the result of simply not being able to afford any slaves, who became increasingly expensive after Congress ended the overseas slave trade in 1808, is unknown.

Owing to the fact that Jeremiah and his wife had been married a little less than two years when the 1820 census was taken, it is quite obvious however that two of the three male inhabitants of this household could not possibly be their sons. One possible explanation is that the two young men enumerated in addition to Jeremiah were either his or his wife Sarah's younger brothers.

There are three land transactions on file in the deed records of Jasper County, Georgia in which Jeremiah West was a party. Here is a list:

- April 20, 1819: Jacob Pinson to Jeremiah West, for $300, lot no. 139 in the 18th District of Jasper County (originally Baldwin County), containing 202½ acres. Wit: S. Perry. Recorded in Jasper County, Georgia Deed Book B, p.250 on February 1, 1820.

- April 21, 1821: Sam Miller to Jeremiah West, for $300, eighty acres in the 18th District of Jasper County (formerly part of Baldwin County), known as No. 138, on the waters of Herds Creek. Wit: John W. (Craig?) and Thomas Williams. Recorded in Jasper County, Georgia Deed Book B, pp.508-9 on October 26, 1821.

- February 22, 1822: Jeremiah West to Joseph Williams (possibly a kinsman of West's wife, Sarah), for $300, eighty acres in the 18th District of Jasper County (formerly part of Baldwin County), known as No. 138. Wit: Samuel Bellah and John Williams. Recorded in Jasper County, Georgia Deed Book B, p.644 on September 5, 1822.

By 1830, Jeremiah and Sarah had moved to nearby Henry County, Georgia, where Jeremiah's mother and father and some of his siblings were then living. In the federal census for that year, the household consisted of one free white male less than 5 years of age (William R.), one free white male 30 to 39 years old (Jeremiah), two free white females age 5 through 9 (born between 1820 and 1825), and 1 free white female 30 to 39 years of age (Sarah). Again, Jeremiah had no slaves.23

Earlier that same year (1830), Congress had voted by a narrow margin (102 to 97 in the House and 28 to 19 in the Senate) to pass the Indian Removal Act, which gave President Andrew Jackson the authority to have the so-called "Five Civilized Tribes"-the Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, who then inhabited Georgia, Tennessee, Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi, removed-by military force if necessary-to a newly-designated "Indian Territory" west of the Mississippi River and north of Mexican Texas.

Although the Creeks seem to have been the most reluctant of the southeastern tribes to leave, in an 1832 treaty the tribe ceded all its lands east of the Mississippi River to the U.S. government. However, despite President Jackson's desire "that the Creeks should remove to the country west of the Mississippi, and join their countrymen there," the treaty contained a provision that allowed any Creek who wished to remain behind to select a half-section (320 acres) of land. Afterward he could either sell it or, after five years, he could receive a deed for it if he still did not wish to emigrate.

This plan turned out to be unworkable in practice. Unfortunately for the Indians, the treaty became a silent signal for thousands of whites to flood into Alabama. Not surprisingly, the Creeks became angry when their lands, promised to them by the treaty, were in effect being stolen from under their noses. Unfortunately, the government did little or nothing to remedy the situation. It took a turn for the worse when a group of destitute Creeks encamped in Georgia in the spring of 1836. After being attacked by Georgia Militia, roving bands of Indians began to attack and kill whites in the area and to destroy property. To subdue the Creeks, and force their removal to the "Indian Territory," 4,755 Georgia militiamen, 4,300 Alabamians volunteers, and 1,103 regular army soldiers under the command of General Winfield Scott were called into service during the spring and summer of 1836. Jeremiah West was among them, enlisting at Columbus, Georgia as a private in the 66th regiment of Georgia Militia.24

Initially, General Thomas Jesup was in command. After Scott arrived from Florida, where he had been fighting the Seminoles, a plan was put into effect whereby Jesup's men would drive the Indians from the west toward Scott's forces, who would sweep from the east. The idea was to catch the Creeks between them.

Creek Indian War. Source unknown.

However, Jesup could scarcely restrain his Alabamians. Despite the plan, he and his men located the main Creek camp where they captured the Indians' leader, Eneah Micco, along with three or four hundred warriors. Although Jesup, by this action, seemed to have brought peace once more to the area, Scott was angry because many Creeks had escaped. In late June the Georgia Militia, possibly including Private Jeremiah West, met and defeated the remainder of the hostile Creeks. By 24 June, General Scott was able to report to Washington, D.C. that the war was over, although for the next few weeks there were still occasional skirmishes with scattered Indian bands.

The following month, the removal of the Creeks began. Handcuffed and chained, and guarded by soldiers, the defeated warriors left Fort Mitchell in neighboring Alabama on 2 July. Wagons and ponies carrying children, old women and the ill followed them. A little less than two weeks later nearly 2,500 more Creeks were put aboard boats at Montgomery and taken down the Alabama River to Mobile for further transportation to their lands in the west. Whether Jeremiah West watched either of these sad scenes is unknown. It is a near certainty however, that he mustered-out at Columbus sometime in mid-summer, his military service having lasted probably only two or three months.

The fact that Jeremiah West enlisted in the Georgia Militia during the Creek Indian War of 1836 informs us that by that time the war occurred he and his family had moved from Henry County to Harris County, Georgia, which is not very far from Columbus, the city that served as General Scott's headquarters. When the 1840 federal census for Harris County was taken, the Jeremiah West household consisted of one free white male between the ages of 10 and 14 (William), one free white male age 40 to 49 (Jeremiah), and one free white female age 40 to 49 (Sarah). The two daughters listed in the previous census had apparently either died or married. As before, Jeremiah West had no slaves.25

In 1841 the Columbus Enquirer carried a short notice stating that as the result of a lawsuit brought by Jeremiah West, which he apparently won, the inferior court of Harris County had ordered one lot and one house in Talleytown, "containing one half acre, more or less" and belonging to one Alfred Hutchinson, had been "levied upon" to satisfy the court's judgement in favor of West.26 No other details regarding this case have been found.

In the 1850 federal census for Harris County, Georgia, this family again consisted of only three persons: 51-year-old Jeremiah, 56-year-old Sarah, and the couple's 22-year-old William R. West. The census shows too that Jeremiah was a middling sort of farmer, with only $600 worth of real estate.27 Apparently for the first time in thirty years he also owned four slaves--one adult male age 30, one adult female age 23, and a seven-year-old boy and a two-year-old girl--who together almost certainly constituted a family.28

Curiously, although the Jeremiah West family lived in Harris County for about fifteen years, there are no deed records on file in that county, in which Jeremiah West was either buyer or seller.

On September 24, 1851, a notice appeared in The Columbus Times, saying that a young man named G. W. Webb, age twenty-six, had died at the home of Jeremiah West, in Harris County, on September 2nd. Nothing is known about Webb or why he would be living with the West family, nor what was the manner or cause of his death.

It appears that sometime shortly after the 1850 census was taken, Jeremiah West and his family moved from Harris County to neighboring Muscogee County, where his father and brother Tillman resided.

There are two land transactions on file in Muscogee County, Georgia in which Jeremiah West was a party. Here is a list:

- May 29, 1851: William Ligon to Jeremiah West, for $450, for a half-acre plot of land "commencing at the west corner of the commons of the City of Columbus, where it intersects the Turnpike Road on the South, thence running east one-hundred-and-thirty-six feet ten inches along the line of said road, thence south one-hundred-and-sixty-seven feet four inches, thence west one-hundred-and-thirty-six feet ten inches, thence to the beginning corner one-hundred-and-fifty feet, it being part of a ten-acre lot on the Coweta Reserve lying and being in the County of Muscogee and State of Georgia." Wit: John Ligon and Michael N. Clarke. Recorded in Muscogee County, Georgia Deed Book F, p.119 on February 7, 1852

.

- November 28, 1851: Jeremiah West to Jackson Bryant, for $5, a 35-foot-square piece of land in a lot [number not noted] in District C. Wit: Britton McCullers and John Brooks. Recorded in Muscogee County, Georgia Deed Book F, p.120 on February 7, 1852.

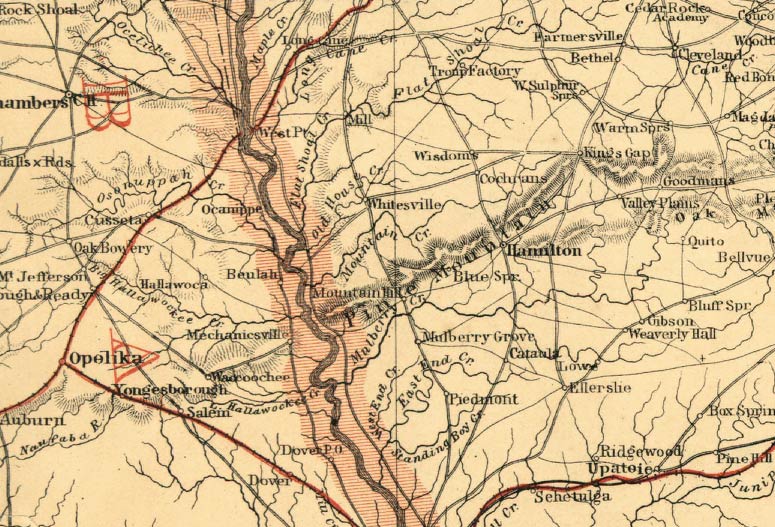

Map of Muscogee and Harris counties in Georgia, circa 1864. Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Sometime shortly after the 1850 census was taken, Jeremiah West and his family moved from Harris County to neighboring Muscogee County, where his father and brother Tillman resided.

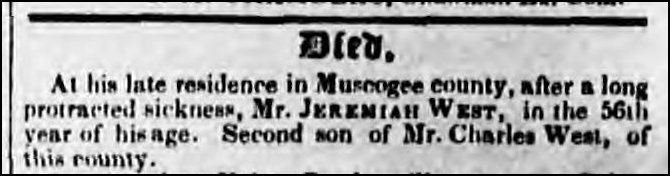

Jeremiah West death notice in the Columbus Enquirer, 16 December 1851.

Sometime in early December 1851, shortly after selling the above-referenced piece of land to Jackson Bryant, Jeremiah West died "at his residence [in Columbus, presumably]…after a long protracted illness." According to a death notice that appeared in the Columbus Enquirer on December 16, he was fifty-six years of age. The notice also identified him as "the second son of Mr. Charles West of this county."29 Unfortunately, the location of Jeremiah West's final resting place has seemingly been lost to history, nor can any will, estate, or probate records be found in Muscogee County, Georgia, which was presumably his last place of residence. If by some chance, he is buried at his father's Westmoreland Plantation, the grave is apparently unmarked. What became of his wife, Sarah, following his death is likewise a mystery. She does not appear in the 1860 federal census.

All we know about Sarah is that on May 7, 1853, shortly after her husband's untimely death, she gave her son, William R. West, "in consideration of natural love and affection," a part of lot 14 (50 acres in the southeast corner) in the 20th District of Harris County (originally part of Muscogee County). The deed, found in Harris County, Georgia Deed Book F, p.375, was witnessed by John U. Brawner and Jacob M. Moon, and filed for record on June 6, 1853.

William R. West (Abt. 1828-1858)

William R. West, the only son of Jeremiah West and his wife Sarah, was born about 1828 in Georgia, either in Jasper County, where his father was listed in the 1820 federal census as the head of a household, or Henry County, where his father was identified as the head of a household in the 1830 census. Unfortunately, nothing at all is known about William R. West's early life except that by the time he reached adulthood, he and his parents were living in Harris County, Georgia.

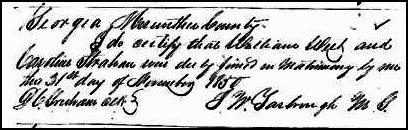

On 21 November 1850, in neighboring Meriwether County, twenty-two-year-old William R. West was married to Mary Caroline Strahan, the nineteen-year-old daughter of a prosperous Meriwether County planter and slave owner named Neil Strahan.30

Marriage record of William R. West and Mary C. Strahan. Courtesy Georgia State Archives, Atlanta, Georgia.

The following December, William R. West experienced a tragedy, namely the untimely death of his father at age fifty-six, which was then followed almost immediately by a much more happy event, namely the birth of his and Mary Caroline's first child--a little girl who was born on 23 December 1851 in Harris County and named Sarah Augusta West,31 apparently in honor of her paternal grandmother.

On 30 December 1854, Mary Caroline West gave birth to another daughter, who was named Mary Jane.32 A little boy named Henry was born about two years later.33

On 5 December 1858, at Mountain Hill, Harris County, Georgia, William R. West died of unknown causes at the age of only thirty.34 Unfortunately, his place of burial, like his father's, seems to have been lost to history.

Map of Harris County, showing Mountain Hill, where the William R. West family lived. Courtesy Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In 1861, William R. West's young widow, Mary Caroline, remarried. Her second husband was a widower, Harrison Tate of Russell County, Alabama. Five years later, William's daughter Sarah married her stepbrother, Isaac Henry Tate, not long after he returned home after serving in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. In 1888, Isaac and Sarah and their children went to live in Texas. After spending two years living in Vernon, Texas, in 1890 they permanently settled in Dallas, where they remained for the rest of their lives. In 1928 Sarah died and was the first member of the family to be buried in the Tate family plot at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Far North Dallas. Her husband passed away in 1932.35

In 1874, Sarah's sister, Mary Jane, married James Henry Byrd and returned to live at or near the community of Waverly Hall in Harris County, Georgia, where she and her husband remained until their deaths at 1927 and 1939 respectively.36

What became of Sarah's brother, Henry West? After reaching adulthood, he went out west, settling for a time in the Indian Territory In 1895, he got married, had lots of children, and moved to Bee County, Texas, where he farmed until his death in 1939.

Mary Caroline and her second husband never had any children together but they were married for thirty years. After Harrison Tate died in 1891 in Columbia, Henry County, Alabama, Mary Caroline continued to live there at least until 1900, when she was listed in a federal census for the last time. After she died on 26 June 1909, she was buried in the Byrd family plot in Waverly Hall Cemetery, Harris County, Georgia.37

NOTES

1Tombstone inscription, West Cemetery, former Westmoreland Plantation, 7400 Warm Springs Road, Midland, Muscogee County, Georgia, 31820.

2Ibid. Sarah's date of birth, 3 July 1773, is inscribed on her tombstone.

3Will of Charles West, Muscogee County, Georgia courthouse, Will Book A, 279-82; Columbus Enquirer, 16 December 1851, 2.

4It should be noted that there was a Charles West in the 1820 federal census for Baltimore County, Maryland and also in the 1830 census for Dorchester County, but neither one should be confused with "our" Charles West, who resided in Georgia in those years.

5U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fourth Census of the United States, 1820: Population, Washington County, Georgia, page 132, NARA microfilm publication M33, roll 9, image 225.

6Ibid.

7Census for 1820 (Washington, D.C.: Gales & Seaton, 1821), 116.

8U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fifth Census of the United States, 1830: Population, Henry County, Georgia, page 210, NARA microfilm publication M19, roll 18.

9U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840: Population, Henry County, Georgia, page 325, NARA microfilm publication M704, roll 43, image 663.

10Tombstone inscription, West Cemetery, former Westmoreland Plantation, 7400 Warm Springs Road, Midland, Muscogee County, Georgia, 31820.

11Marriage Book 1808-1820, page 154, Muscogee County courthouse, Columbus, Georgia; John B. Martin, compiler, Columbus, Georgia from Its Selection as a "Trading Town" in 1827 to Its Partial Destruction by Wilson's Raid in 1865, Part I-1827 to 1846 (Columbus, Georgia: Thomas Gilbert, Book Printer and Binder, 1874), 131; Tombstone inscription, West Cemetery, former Westmoreland Plantation, 7400 Warm Springs Road, Midland, Muscogee County, Georgia, 31820. Clarissa's tombstone states she was born in 1790.

12U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Population, Muscogee County, Georgia, page 384A, NARA microfilm publication M432, roll 79, image 180.

13U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Slave Schedules, Muscogee County, Georgia.

14Westmoreland's date of construction was obtained from the Muscogee County property tax assessor's office in Columbus, Georgia.

15Tombstone inscription, West Cemetery, former Westmoreland Plantation, 7400 Warm Springs Road, Midland, Muscogee County, Georgia, 31820.

16U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Population, Muscogee County, Georgia, page 371, NARA microfilm publication M653, roll 132, image 371. This census actually gives Charles West's age as 94 but this is unlikely since it is inconsistent with earlier census records. He was almost certainly 90 years of age however.

17U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860: Slave Schedules, Muscogee County, Georgia.

18Tombstone inscription, West Cemetery, former Westmoreland Plantation, 7400 Warm Springs Road, Midland, Muscogee County, Georgia, 31820.

19Columbus Enquirer, Columbus Georgia, 10 July 1860, 3.

21Tombstone inscription, West Cemetery, former Westmoreland Plantation, 7400 Warm Springs Road, Midland, Muscogee County, Georgia, 31820.

21Unfortunately, I cannot recall where I found this date of birth but it probably came from some other researcher who did not cite his or her source. Census records and a newspaper obituary notice put Jeremiah West's year of birth as sometime between 1794 and 1799.

22U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fourth Census of the United States, 1820: Population, Jasper County, Georgia, page 220, NARA microfilm publication M33, roll 6, image 131.

23U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fifth Census of the United States, 1830: Population, Henry County, Georgia, page 225, NARA microfilm publication M19, roll 18.

24National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During Indian Wars 1815-1858, War-Whid, NARA microfilm publication M629, roll 40.

25U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840: Population, Harris County, Georgia, page 277, NARA microfilm publication M704, roll 43, image 567.

26Columbus Enquirer, Columbus Georgia, 24 November 1841, 4.

27U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Population, Harris County, Georgia, page 90B, NARA microfilm publication M432, roll 73, image 83.

28U. S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Slave Schedules, Harris County, Georgia.

29Columbus Enquirer, Columbus, Georgia, 16 December 1851, 2.

30

31Tate family Bible in possession of the author.

32

33

34I cannot remember where I found William R. West's date of death but I feel certain that it is accurate. There is no question that he died sometime between the birth of his son Henry, about 1856, and 1860.

35See "Tate Family" history by the author.

36Tombstone inscription, Waverly Hall Cemetery, Harris County, Georgia.

37Tombstone inscription, Waverly Hall Cemetery, Harris County, Georgia.

|