The Ward Family

Ward Family MATTHEW WARD I cannot say with certainty whether the Mathew Ward mentioned in the introductory paragraph was the progenitor of the family from whom we are descended, or not. In any event, I am most certainly descended from another Mathew Ward, who was born about 1765. probably in either Virginia or North Carolina. In 1790, the first year a federal census was taken, this particular Mathew Ward was living as a single man in Duplin County, North Carolina. Very little is known about him, but he came from a large family, apparently--there being several other heads of households named Ward who were also enumerated in Duplin County in the same census. Duplin County was formed in 1750 from New Hanover County. Its seat was, and still is, the town of Kenansville-named for the family of Colonel James Kenan, who in 1765 led a group of volunteers from Kenansville to Brunswick to protest the hated British Stamp Act. Passed by Parliament in 1765, the act was repealed a year later after enforcement was found to be nigh impossible. The county was named for Lord Duplin, a British nobleman. Many of the earliest residents were Scots-Irish from Ulster who came to America under the patronage of Henry McCulloch-a wealthy London merchant who was granted large tracts of land in North Carolina by King George II. Some researchers hold that Mathew Ward was born in Martin County, North Carolina, and that he is the same Mathew Ward who is listed as a private in a regiment of Revolutionary War volunteers from Martin County, a unit that also included a Captain Francis Ward. Although it is possible that Mathew Ward served in this capacity, in view of the fact that "our" Matthew was only about fifteen in 1780, the year that the British army's southern campaign began, I think more work needs to be done to ascertain whether the man named in the roster is the same Mathew Ward who resided in Duplin County after the war. About 1792 Mathew Ward married Ann Ellison, daughter of Jesse Ellison, who in 1784 and 1787, was enumerated in the state census of North Carolina. At that time, Ellison was living in Martin County, just west of Albemarle Sound and a few counties north of Duplin, which lends weight to the notion that Mathew Ward was likewise a resident of Martin County. Ellison and his wife, Ann, whose maiden name is unknown, had eight children: four each of boys and girls, one of which was Ann. In that same state census, five men named Ward were found living in Duplin County. Any one of three, Philip, William, or Daniel, could have been Mathew Ward's father. Most researchers have pointed to Philip, but without providing any evidence to back up their choice. Unfortunately, early census records named only the heads of households. Jesse Ellison was one of those enumerated in the 1790 federal census for Duplin County, his name appearing immediately above Mathew Ward's. Matthew and Ann Ward had at least seven children: three boys and four girls--all of which were probably born in Duplin County.

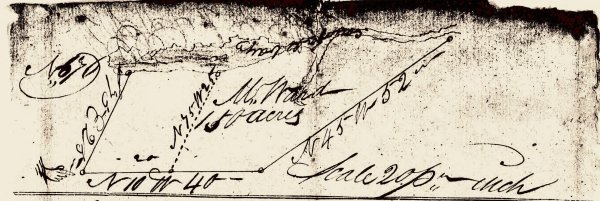

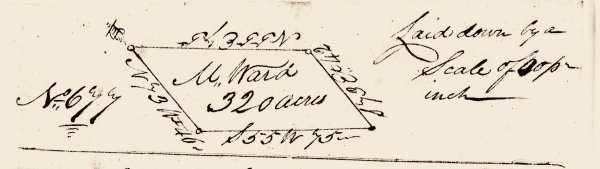

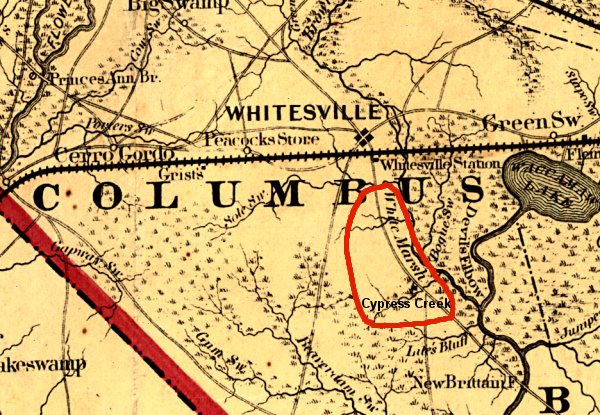

Federal census records reveal that Matthew and Ann Ward had a few other children that apparently did not survive to adulthood. Unfortunately, their names have been lost to history. Like most North Carolinians of the era, Matthew Ward was a "planter." During his lifetime he bought and sold several tracts of land, first in Duplin County, and then in Columbus County, to where he moved sometime between 1808--the year it was formed from portions of Bladen and Brunswick counties and named for the explorer, Christopher Columbus--and 1815. In Ward's first known land transaction in Duplin County, dated November 2, 1797, he paid "two hundred pounds specie" for two tracts, one of 100 acres and the other of 300 acres, from Isaac Hines of Lenoir County, "on the No. side of the No. East, including the plantation the said Matthew Ward now lives on." How and when he obtained the property on which he was already then living is unknown. Its size is likewise unknown. On April 10, 1799, the State of North Carolina awarded Ward a grant (#1696) for 120 acres in Duplin County. A county deed book record of the grant, dated December 5, 1800, describes this property as being located on "the East side of the N. E. side of the N. E. Buck Marsh." In or around July 1804, Matthew Ward's father-in-law, Jesse Ellison, died in Duplin County. In his will, dated June 25, 1804, Matthew Ward was identified as Ellison's son-in-law, and also named as one of two executors of his estate. (The other was Ellison's wife, Ann.) In 1808, while serving in this capacity, Matthew Ward sold his deceased father-in-law's own extensive land holdings for 476 Pounds, so that the money could be distributed among his heirs. On February 4, 1808, for 476 Pounds, Mathew Ward sold 670 acres of land in Duplin County to William Turnage of Green County. Most of this property consisted of the two tracts conveyed to him (Ward) by deed from Isaac Hines. On December 22, 1808, a notice appeared in the Weekly Raleigh Register, announcing an auction for the following January 20, at which the Sheriff of Columbus County would be selling several pieces of property to satisfy the back taxes due on them. Near the top of the list was 575 acres belonging to Matthew Ward. Unfortunately, there seems to be no record of this sale in county deed records, leaving us to wonder if Ward redeemed his land by paying his back taxes, or if he lost it. In either event, it has long been assumed that soon after disposing of and/or forfeiting his land in Duplin County, Mathew Ward and his family immediately moved to newly-formed Columbus County, the seat of which is Whiteville. Founded in 1810, the town was named for James B. White, who gave land for the site of the first courthouse and jail. However, in 1810, the federal census-taker for Columbus County, North Carolina, found only an "M. Ward" family consisting of four free white females under the age of ten, one free white female between ten and sixteen, and one free white female between the ages of sixteen and twenty-six. Since no males of any age are included in the enumeration of this particular family, this record cannot possibly be for the family of Matthew Ward. But where was he in 1810? He cannot be found in the 1810 federal census for Duplin County either. The only county in which a Matthew Ward can be found, with a family that matches by both sex and number is one in Lenoir County. The possibility that Matthew Ward resided for some years in Lenoir County after selling his land in Duplin County in 1808 is supported by the fact that there is no evidence of his presence in Columbus County prior to 1814, when Mathew Ward, "planter," purchased 540 acres "on the southwest side of Western Prong" (a community located eight miles north of Whiteville) from Noah Allen, for $160. In 1815 he purchased two 200-acre Columbus County parcels from John Stevens, 400 acres in all, for which he paid $600. These tracts, according to the descriptions in the deed, were located near Cypress Creek. That same year (1815), in return for the payment of an undisclosed amount of "Purchase Money," the State of North Carolina granted Ward a further 150 acres of land located "on the west side of the White Marsh [Swamp or River], joining his own lines & James Corbett Junr.'s line." On March 12, 1816, a warrant was issued, authorizing a survey of this property, which was done on September 16, 1816. A patent for this grant (no. 228) was issued on December 17, 1816. A warrant authorizing the survey of an additional 320 acres on the west side of White Marsh, was likewise issued on March 12, 1816. It was carried out on the same date, September 16, 1816, that his 150-acre grant was surveyed. Both surveys include a map, but neither one includes any distinguishing landmarks to help ascertain their precise location.

On November 8, 1816, Matthew Ward bore witness to a sale of land from Gabriel Merrit to Saul Smith (recorded in Columbus County, North Carolina Deed Book C, p.366.). On August 22, 1817, Ward purchased two more tracts of land, one of 100 acres and the other and adjoining 50 acres, on "the White Marsh [Swamp or River] west side of Cypress Creek," for which he paid James Corbett, Jr. $120. On November 17, 1818, Corbett sold Ward a further 276 acres on "both sides of Cypress Creek," along with a smaller adjoining 24-acre tract. The price this time was $276, slightly less than a dollar an acre. On that same day, he also paid Thomas Cribb $75 for 100 acres near Possum Island. The funds to pay for these three tracts were almost certainly derived from the November 9 sale of "a certain negro man named November" to one Lewis Williamson for $650. Cumulatively, these sales provide evidence that at that time, slaves were much more expensive than the land they were forced to work! Thus, by the end of 1818, Matthew Ward was the owner of 1,960 acres of land in Columbus County, North Carolina, far more than he could have possibly cultivated with only three sons and a handful of slaves to help him. This begs a question: Why did he feel compelled to possess such a large quantity of real estate? According to all these surviving deed records, the White Marsh Swamp, a vast cypress-filled wetland fed by the White Marsh River, lay along the eastern edge of most of Matthew Ward's landholdings. Even today, the White Marsh Swamp is one of the most outstanding geographic features of Columbus County, North Carolina. On aerial or satellite maps of the county, it appears as a huge, green, irregular Y-shaped expanse, with Lake Waccamaw, another hard-to-miss geographic feature, to the east. On the west side, Cypress Creek, referenced in most of the deeds concerning Mathew Ward's land transactions, drains into the White Marsh Swamp. Although it would difficult today to ascertain the precise shape and boundaries of any portion of Ward's property (largely because live trees were most often cited as boundary markers), the frequent mention of both White Marsh Swamp and Cypress Creek provide us with a general idea of its location, as does the present-day Pleasant Plains Baptist Church, which stands today at the junction of Pleasant Plains Church Road and NC State Highway 130, nearly eight miles directly south of Whiteville. Fourteen years after Ward's death, his heirs gave the church the five acres which it had apparently previously rented from either them or Matthew Ward, on the north side of Cypress Creek. A small cemetery adjacent to the church contains the graves of some later members of the Hill and Sasser families that Matthew Ward's daughters married into. One of these marked graves contains the remains of the Reverend George Washington Hill, whose father was the very same Joel Hill who bought 100 acres from Matthew Ward in 1821. (See second paragraph below.)

In 1820, when the federal census for Columbus County, North Carolina was taken, the Ward household included: Matthew, who by then was about fifty-five years of age; his wife, Ann, who was probably forty-five or close to it; a son under 10, name unknown; two sons more than 10 and less than 16, names unknown; Morris, about eighteen, and Robert, about twenty-four; daughter Sarah, under 10; a daughter between 10 and 16, name unknown; and Nancy, who was then about twenty-four. Mathew also owned six slaves: 2 males under 14; one male over 45; two females under 14; and one female between 14 and 26. On February 5, 1821, for $150 paid to him by Joel Hill, Matthew Ward sold 100 acres of his land on the southwest side of the White Marsh Swamp. A dozen years would pass before he parted with any more. In 1830, the Columbus County, North Carolina federal census-taker found that the Mathew Ward household consisted of one white male age 15 to 20 (probably Francis), one white male between 20 and 30 (almost certainly Morris), one white male between sixty and seventy (Mathew, obviously), one white female between 20 and 30 (most likely Sarah), and one white female between 40 and 50 (Ann). There were also seven slaves (two males under 10, one male between 10 and 23, one male between 36 and 54, two females under 10, and one female between 24 and 35). In the summer of 1833, Matthew gave his "beloved son, Morris Ward" two tracts of 100 acres each, out of his holdings on the west side of the White Marsh Swamp. At the time, Morris was thirty-one years old, recently-married to the daughter of Edward Wilson, and the father of a year-old son, Robert, who was almost certainly named in honor of Morris' brother, Robert. On December 11th of the following year, probably because he needed money to help facilitate a move to Alabama, Morris Ward sold one of these 100-acre gift tracts back to his father for $305, and on the very same day he sold the other 100-acre tract to his brother Francis for $150. Shortly thereafter, he and his family removed to Pike County, Alabama, where they would reside until the late 1850s, at which time they moved again, this time to East Texas. On December 18, 1839, in return for $250, Matthew Ward bought two tracts of land "on the east side of Cypress Creek," totaling 150 acres, from his son, Robert. A little more than a week later, Robert purchased the 300 acres that his father had bought from James Corbett, Jr. in 1818, paying him a dollar per acre. The reason for these two nearly simultaneous transactions is unknown. The 1840 federal census for Columbus County shows that the Mathew Ward household consisted of only two free white people-Mathew and Ann-now both quite old, and four slaves (one male 24 to 35, one female under 10, and two females 10 to 23). On Tuesday evening, February 9, 1841, following "a long and painful illness of 49 days," Mathew Ward, age seventy-five, died at his plantation home, on the west side of the White Marsh Swamp. Soon after, an obituary appeared in the Weekly Standard of Raleigh, which noted that the family he left behind consisted of "a wife, three sons [Robert, Morris, and Francis] and four daughters [Elizabeth, Nancy, Sarah, and Hallie], a part of them being in other states." Unfortunately, if Matthew Ward wrote a will, it has not survived, nor, apparently, was it entered into any public record. However, thanks to newspaper notices and Columbus County court and deed records, we can not only identify his heirs, but also ascertain what became of at least some of his property. During the May 1841 term of the County Court of Pleas and Quarters, "Robert Ward & Nancy Ward" were "granted letters of administration on the estate of Matthew Ward, deceased" by "giving for security a bond…of five thousand dollars." A separate entry for the same court term reads: "Nancy Ward & Robert Ward entered in to Admr. Bond on the estate of Mathew Ward decd. in the sum of five Thousand dollars-with David George, Josiah Maultsby, Jacob Powell & Nathan Williamson as securities." These same individuals were listed in both notations. It is also interesting to note that in both instances, Nancy Ward, Robert's sister and Hardy Hill's wife, was in all likelihood named in error. In all subsequent records pertaining to Matthew Ward's estate, Matthew's widow, Ann, is identified as an administrator. During the court's August 1841 term, it was reported that Robert Ward, "admr. of M. Ward" had filed an inventory of his father's estate. Unfortunately, no surviving record of this inventory can be found in this or any other Columbus County records. At the same time, Ann Ward filed suit against Robert and all of Matthew Ward's other heirs, petitioning "for Dower," that is for the legal right to a portion of her late husband's real estate. Because it was known that both Morris Ward and Francis Ward no longer resided in the area, the court ordered that, "publication be made in the Wilmington Chronicle, a newspaper published in the town of Wilmington, for five successive weeks, notifying the said Morris Ward and Francis Ward to appear at the next Term of our Court of Pleas & Quarter Sessions to be held for the county of Columbus, at the Court House in Whiteville on the second Monday of November next, then and there to plead for said petition, or the prayer of the Petitioner will be granted." The whereabouts of Francis Ward at this time are unknown to this researcher, but Morris, as everyone in his family surely knew, was then living in Pike County, Alabama, and was highly unlikely to read the Wilmington Chronicle, unless a friend or family member mailed him a copy, and even then, it is equally unlikely that he would have received it in time or bothered to travel all the way back to North Carolina to contest what most people of the time would probably have considered a perfectly reasonable request. Furthermore, it is not likely that this this lawsuit was brought in any sort of adversarial fashion, but rather as a routine legal procedure. Unsurprisingly, when the court reconvened in November, neither Morris or Francis were anywhere to be seen. Consequently, the court approved Ann's petition for dower. During that same November term, the court reported that Ann, together with all four of her daughters (and their husbands), had filed a lawsuit against brothers Robert, Morris and Francis-or rather, Maurice and Frank, as the latter two were misidentified in the official record-in which the court was asked to approve a partition of Matthew Ward's five slaves. As before, the court responded by "commanding the said Maurice and Frank Ward to be and to appear before the next Court of Pleas & Quarter Sessions for the County of Columbus, at the courthouse in Whiteville on the second Monday of February next, then and there to show cause why the prayer of the petitioners should not be granted." In accordance with the court order, a notice of the petition was published in the Wilmington Chronicle, and, as before, when the next term began (in February), Morris and Francis were no-shows, which is probably what everyone involved in the matter had expected all along. Consequently, the court granted the petition and appointed one James Smith to sell the slaves, who were named in the record-Yorick [or York, more likely], Barbary, Rachel, Eliza and Sandy-"after giving thirty days publick [sic] notice upon a credit of six months purchaser giving bond." What became of these slaves has apparently been lost to history, except for Yorick [York], who was sold to James Smith himself on September 2, 1842, for $600. In January 1846, Ann Ward devised a will, identifying herself as the widow of Mathew Ward. In it, she named only her son Robert Ward, Hardy Ward (a grandson, perhaps?) and his unnamed wife, and an underage young man named Francis O. Milliken, "the son of Winna Milliken, a lad who now resides with me," to who she bequeathed the sum of $100. Milliken's relationship to Ann Ward is uncertain. None of her daughters married a Milliken, so he is unlikely to be a grandchild. Although advanced in age, Ann Ellison Ward was still alive on October 27, 1847, when she and all of Matthew Ward's other heirs, except Francis, who was apparently dead by this time, and Morris, still living in Alabama and therefore represented by an agent, in this case Matthew G. Sasser (son of Morris's sister Sarah), approved the sale of 100 acres of Matthew Ward's land, for $70, to Joseph Ward, a relative no doubt, but whose relationship to the others is unknown to this researcher. This land, which lay on "the edge of Possum Island," was the same property that Matthew Ward had purchased from Thomas Cribb nearly thirty years earlier, in 1818, for $75. Two months later, on December 20, 1847, almost all the same people-in this case Ann Ward, Robert Ward (acting on his own behalf and also as agent for his brother, Morris), Elizabeth Ward Sasser, Sarah Ward Best and husband, James, James's apparently widowed brother Henry Best, and Nancy Ward Hill and husband, Hardy Hill-as "the legal heirs of Francis Ward, deceased," sold 200 acres of land, "more or less," to a man named Joseph Stephens, for $225. What makes this transaction particularly interesting to the descendants of Matthew Ward is the deed's description of the property as lying "on the South West Side of the [White] Marsh Swamp including the plantation where Matthew Ward formerly lived and died and all the island plantation in the [White] Marsh Swamp Patented by Thomas Edwards Grant bearing date February 15, 1798." This suggests that Francis Ward inherited his father's plantation, or at least the heart of it, but precisely what happened to Francis himself, when and where he died, has unfortunately been lost to history. No will or probate record of any kind can be found in the records of Columbus County, North Carolina. One may exist elsewhere, but where? On the same day, December 20, 1847, the above-named heirs of Francis Ward sold a further 100 acres of his property, near Cypress Creek, for $101, to one Henry Thompson, and also a 50-acre tract, for $60, to William Ward, almost certainly a relative, perhaps a cousin. In November 1848, Ann Ward's will was proven in the Court of Please and Quarters by the testimony of Calvin Sasser, and then offered for probate by her son, Robert, who was approved as executor of her estate. This suggests that Ann died sometime between the previous court term, in August, and this one. The entry immediately above, records that Matthew G. Sasser was appointed executor of the estate of his father, Frederick Sasser, husband of Sarah Ward Sasser, which seems odd considering that Frederick had died some two years earlier, in 1846, with much of his property already disposed of. Unfortunately, the location of the final resting place of both Matthew Ward and his wife, Ann, who were almost certainly buried in the same place, has been lost to history. The strongest possibility, in the view of this researcher, is the Pleasant Plain Baptist Church burial ground, but if so, there are no visible markers to confirm it.Epilogue: In the 1870 federal census for Hertford County, North Carolina, there is a sixty-year-old black farmer named York Ward listed, along with his sixty-year-old wife, Mary. Is this the same man who was sold as a slave to James Smith by the heirs of Matthew Ward in 1847? Although Hertford County is a long way from Columbus County, York could have been sold more than once between 1847 and emancipation in 1865. It is interesting to note also that in 1870, there were no fewer than three African-American individuals named York Ward living in Columbus County, none old enough to be the same person sold as a slave in 1847, but the persistence of the name suggests that two, age 24 and 11, living in different households, could be his son, and the third, age 11, a grandson.

Ward Family

This website copyright © 1996-2022 by Steven R. Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved. |