A Centennial History of the White Rock Dam

Or, "If You Dam It, They Will Come."

Adapted from the Centennial Edition of Steven R. Butler's From Water Supply to Urban Oasis: A History of White Rock Lake Park (Richardson, Texas: Poor Scholar Publications, 2004 & 2011).

See also: Centennial Timeline of the White Rock Dam.

In the late nineteenth century, city officials soon began looking for solutions to Dallas' increasing water needs. The need became even more urgent in 1896 when the West Fork water became unpalatable due to pollution that originated in Fort Worth. Subsequently, a dam was built across the Elm Fork of the Trinity at Record Crossing and a new pump house was built. Seven years later Bachman Branch, a creek that flows west into the Elm Fork of the Trinity River, was dammed to create a 142 surface acre reservoir. Located about 6˝ miles northwest of Dallas, it soon became known as Bachman's Lake.

Although the new reservoir was not built with leisure activities in mind, its shoreline, dotted here and there with trees, quickly became a popular destination for city dwellers seeking recreation. By 1905 there were campgrounds and a rowboat concession.

Although the new reservoir was not built with leisure activities in mind, its shoreline, dotted here and there with trees, quickly became a popular destination for city dwellers seeking recreation. By 1905 there were campgrounds and a rowboat concession.

As Dallasites streamed north on the Denton Road to enjoy the country atmosphere of Bachman's Lake, traveling by horse and carriage (and some, no doubt, by motor car), city officials came to the realization that the new reservoir was already becoming inadequate. In 1907 they began to plan for the construction of a larger impound. "After careful studying the surrounding country," wrote a civil engineering student who later prepared a detailed study of the project, "they decided," some twenty-seven years after it was first recommended by a pair of engineers named Smith and Davis, "to put a dam across a large surface water creek called White Rock."

The narrow valley it was proposed to inundate with water lay about four miles in a northeasterly direction from the county courthouse. Surrounded by hills that were as much as 39 feet above the valley floor, it seemed the best possible place to put a reservoir owing to the land's elevation and its natural slope toward the city and the Trinity River. Test holes bored to a depth of 24 feet revealed that the "black, waxey soil" was from ten to twenty feet deep over a subsequent layer of clay and gravel but in some places the earth was "only a few feet deep over the rock." It was this underlying layer of white rock, engineers hoped, that would prevent the water from seeping into the soil. The only drawback, as far as anyone could tell, was that the creek valley contained "some of the best farming lands in the county." Consequently, "the cost of the property was quite high." Between 1907 and 1910, the city spent approximately $135,000 in bond money for land purchases. The city also paid two men, S. Bev Scott and M.H. Mahana, $5,600 "for the work they performed as agents of the city in purchasing land for the dam and reservoir site on White Rock." Unfortunately, several property-owners were unwilling sellers. One of these was Jacob Buhrer. In February 1910 a portion of his Swiss Dairy was acquired for $17,000 after the city filed (and then afterward withdrew) a condemnation suit. Lawsuits, most of which went ahead, were also brought against other landowners. By March 5, 1910, the City of Dallas owned slightly more than 1,698 acres, for which it had paid a total of $114,858.49.

Prior to construction, City Engineers J.M. Preston prepared a map that showed the location of the proposed reservoir as well as a cross section view and an outline of the shape the lake was expected to take. A comparison of this map with contemporary renderings reveals that it was remarkably accurate. Statistics and costs were also included. The drainage area of the reservoir was estimated at 114 square miles and its depth was expected to be 28˝ feet "over valley at base of dam, when…full." With an average annual rainfall of 35 inches (based on records kept during the fifteen-year period from 1893 to 1908), engineers expected a yearly intake of 20 billion gallons of water. The overall holding capacity of the new reservoir was anticipated to be 5,785,000,000 gallons.

Prior to construction, City Engineers J.M. Preston prepared a map that showed the location of the proposed reservoir as well as a cross section view and an outline of the shape the lake was expected to take. A comparison of this map with contemporary renderings reveals that it was remarkably accurate. Statistics and costs were also included. The drainage area of the reservoir was estimated at 114 square miles and its depth was expected to be 28˝ feet "over valley at base of dam, when…full." With an average annual rainfall of 35 inches (based on records kept during the fifteen-year period from 1893 to 1908), engineers expected a yearly intake of 20 billion gallons of water. The overall holding capacity of the new reservoir was anticipated to be 5,785,000,000 gallons.

(You can view a larger digital version of the White Rock reservoir site map at the Murphy and Bolanz map site hosted by the Dallas Public Library.)

Ironically, Dallas experienced severe flooding in May 1908 when heavy rains caused the Trinity River to overspill its banks, not only forcing many people to abandon their homes and businesses but also causing extensive property damage and some loss of life. The following year it must have seemed as if Mother Nature was playing some sort of cruel trick when the opposite dilemma, a long and terrible drought, ensued. At the height of the crisis "insurance companies threatened to withdraw all fire insurance from the city" and drinking water, supplied from artesian wells, had to be delivered to city households by horse-drawn tank wagons. Everywhere, "grass, shrubs and flowers and many trees died."

|

Dallas City Engineer James Montgomery Preston In 1909, 46-year-old City Engineer J. M. Montgomery designed the 2,100 foot long dam that makes White Rock Lake possible, and for 18 months in 1910 and 1911 he oversaw its construction. Born in Athens, Georgia in 1862, Preston came to Texas in 1888. In 1907, after working in the engineering department of the Texas & Pacific Railroad, he was appointed Dallas City Engineer by Water Commissioner Dan Sullivan during the adminstration of Mayor Stephen Hay. Preston also served during the administration of succeeding Mayor Wm. M. Holland. After leaving his post with the City of Dallas, he spent the rest of his life working in his chosen career. Following his death at age 70 in 1932, he was buried at Dallas' Grove Hill Cemetery. He was survived by two sons, a daughter, and his English-born wife Helen. |

One result of the 1909 emergency was to convince city officials that there could not be a better time to go ahead with their plans for the White Rock reservoir. On January 11, 1910, during the administration of Mayor Stephen J. Hay, city commissioners formally adopted "specifications for the work at the White Rock reservoir." These plans, drawn up by Dallas City Engineer J. M. Preston and approved by Hydraulic Engineer John B. Hawley of Fort Worth, called for a 40-foot high, 15-foot wide dam to be made of wooden pilings and earth faced with concrete on the reservoir side. A pump house, necessary for getting the water out of the lake and into city mains, was also planned. The following Sunday, and for three weeks afterward, public notices were published in newspapers in Dallas, Houston, and St. Louis, calling for bids to construct "the foundation for the pumping station…the dam, spillway and other appurtenances at the White Rock reservoir site." Notices also appeared in at least two trade journals, the Manufacturer's Record and the Engineering Journal.

|

William Barclay Parsons, Consulting Engineer In addition to John B. Hawley of Fort Worth, Dallas city officials also contracted with William Barclay Parsons of New York City (but a former Texas resident) to serve as a consulting engineer to the White Rock Reservoir project. Barclay, who was paid $5,000 for his services, had an impressive resume. By the time he came to Dallas in October 1909 to meet with City Engineer Preston and others, Parsons had designed the Cape Cod Canal, worked as Chief Engineer of the New York City subway system, been connected with the construction of the Panama Canal, and had built a railroad in China. During the Spanish-American War he had served in the army with the rank of Colonel. In World War I, he would become a general. |

By early March, six bids had been received-one from a construction company in Junction, Kansas, another located in St. Louis, one in Houston, one in Fort Worth, and two in Dallas. On March 7, the contract was awarded to the Fred A. Jones Company of Dallas, which submitted the second lowest bid. City officials explained that the very lowest bid, which was made by the Texas Building Company of Fort Worth, "could not be entertained" because the firm had not conformed "to the specifications and bidding requirements." The city's contract with the Jones Company, which required the firm to began construction within ten days from March 7, 1910 and be finished within 330 days of that date, was signed on March 22.

By early March, six bids had been received-one from a construction company in Junction, Kansas, another located in St. Louis, one in Houston, one in Fort Worth, and two in Dallas. On March 7, the contract was awarded to the Fred A. Jones Company of Dallas, which submitted the second lowest bid. City officials explained that the very lowest bid, which was made by the Texas Building Company of Fort Worth, "could not be entertained" because the firm had not conformed "to the specifications and bidding requirements." The city's contract with the Jones Company, which required the firm to began construction within ten days from March 7, 1910 and be finished within 330 days of that date, was signed on March 22.

Although Jones' company enjoyed an especially harmonious relationship with city commissioners, an apparent disregard for the safety of the workers--from 75 to 100 men who lived in tents on-site--resulted in "several mishaps" that prevented the project from being completed by the original February 23, 1911 deadline. (It is equally possible that the workers themselves had a careless attitude.) Readers should keep in mind that the White Rock dam was constructed in an era when there were practically no laws governing workers' health and safety. There were likewise no social safeguards, such as unemployment insurance, workmen's compensation, or disability insurance. The men who constructed the dam and spillway worked long hours (sometimes including Sundays) for meager pay ($2 per day for unskilled workers). Until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 was passed during the "New Deal" era, it was not uncommon for laborers to be on the job for 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week. Moreover, Texas was a place that was particularly hostile toward labor unions, which elsewhere might have at least made an attempt to improve working conditions.

The first incident that was serious enough to be reported in newspapers occurred on Monday, June 13, 1910, when a "quantity of cement" fell on a workman named Jerry Collins while he unloading it in a storage room. At Saint Paul's Sanitarium in East Dallas, where the 30-year-old laborer (a "white man" it was noted) was taken for treatment, it was last reported that he was in "critical condition:" with several broken ribs and internal injuries. No further mention of Collins can be found in the press. Whether he died or recovered is unknown.

A second serious incident occurred during the late afternoon of November 15, 1910, when a leg collapsed on one of two derricks-one stationary, the other swinging-used in constructing the dam. When this occurred, a cable that held the swinging derrick erect "gave way," causing it to collapse, sending two workmen hurtling 60 feet to the ground. The most seriously hurt was a man named M. Thomas (probably Manley Thomas, identified in the 1911 city directory as a carpenter), who was transported by ambulance to St. Paul's sanitarium in East Dallas with his "right leg broken above the ankle…bone of the leg pushed through the heel, left leg broken at [the] ankle, both feet crushed and injured about [the] head and upper part of body." The other man who fell, J. Greathouse, was also a carpenter. He was taken to St. Paul's as well, having suffered a broken left leg, broken left arm and "bruising about the head and torso." Five men on the ground, "struck by falling lumber or pieces of machinery," were likewise injured, two badly enough to receive hospital treatment. Only one of the affected workmen, an anonymous Mexican laborer, "was not hurt seriously enough to be removed from the work."

A second serious incident occurred during the late afternoon of November 15, 1910, when a leg collapsed on one of two derricks-one stationary, the other swinging-used in constructing the dam. When this occurred, a cable that held the swinging derrick erect "gave way," causing it to collapse, sending two workmen hurtling 60 feet to the ground. The most seriously hurt was a man named M. Thomas (probably Manley Thomas, identified in the 1911 city directory as a carpenter), who was transported by ambulance to St. Paul's sanitarium in East Dallas with his "right leg broken above the ankle…bone of the leg pushed through the heel, left leg broken at [the] ankle, both feet crushed and injured about [the] head and upper part of body." The other man who fell, J. Greathouse, was also a carpenter. He was taken to St. Paul's as well, having suffered a broken left leg, broken left arm and "bruising about the head and torso." Five men on the ground, "struck by falling lumber or pieces of machinery," were likewise injured, two badly enough to receive hospital treatment. Only one of the affected workmen, an anonymous Mexican laborer, "was not hurt seriously enough to be removed from the work."

A follow-up story which appeared the next day in the Dallas Morning News remarked that "all the injured men were getting along as well as could be expected under the circumstances," adding that not just one but both of Thomas' legs were broken. The paper also noted that during the estimated ten days it would take to repair the damaged derricks, "work at White Rock…will decrease…by about 25 per cent."

A third accident, this time undoubtedly fatal, occurred on January 21, 1911. Two men, J. Jarado or Jirado and Charlie Drake (both of whom were African-American), were using dynamite to blast tree stumps out of the ground when a charge exploded unexpectedly, killing Jarado and injuring Drake. The injured man afterward successfully sued the Fred A. Jones Company for negligence, receiving damages in the amount of $1,500 (which was a considerable sum for a working man in those days). All that is known about Jarado (or Jirado) is that his mother and brother traveled to Dallas from their home in Bryan, to collect his body.

Another fatal accident occurred on May 21, 1911 when a boiler that ran a cable exploded, scalding a 25-year-old fireman or boiler tender, James Murphrey, whose back was also broken. Although the injured man was still alive when he was rushed in an ambulance to the Baptist Sanitarium in East Dallas, he "lived only thirty minutes after arriving there." On May 23, he was buried at Oakland Cemetery in South Dallas.

On June 4, 1911, the Dallas Morning News reported, "Sang Kelly, a negro, was shot three times…in a difficulty that occurred at the White Rock reservoir," adding that he was treated for his wounds, which were apparently not fatal, "at the Emergency Hospital." Three days later, a "negro" named M. Isler was "treated at the Emergency Hospital…for wounds which he said he received at the hands of another negro at White Rock reservoir." Unfortunately, the paper failed to report whether the two men were employees of the Jones Company (although it seems likely) or whether the two incidents were related.

Yet another accident occurred on June 25, 1911, when a workman named C. G. Thomas "fell from a platform…and was painfully injured about the head and lower limbs." After being treated "by Dr. C.M. Rosser" at "the Baptist Sanitarium," it was remarked that he was "resting quietly" and had suffered no broken bones. Presumably, Thomas recovered.

The last reported accident related to the reservoir's construction occurred on January 29. 1912, after the dam was completed. The Dallas Morning News reported: "George Lawrence, a negro, about 35 years of age, engaged in blowing out stumps on the White Rock reservoir site...was badly injured...by explosion of a charge of giant powder and dynamite, either fired prematurely or before the man could get out of the way." After he was taken to St. Paul's Sanitarium for treatment, it was further reported that Lawrence, whose "face and upper part of his body" had "suffered most," was likely to lose his sight.

In 1981 the authors of a privately-published history of the Dallas Water Utilities wrote that the the dam was "completed and closed off" by June 24, 1911. This is inaccurate. Although the dam's sluiceway was temporarily closed around that time, it was not permanently sealed until early September. At the same time, the Daily Dallas Times Herald reported that "the upstream guard of the spillway" and "the filling for the sluiceway" were still unfinished. A day earlier, Consulting Engineer John B. Hawley visited the reservoir site, where he estimated that approximately 800 million gallons of water had already been impounded and declared his belief that when full, the reservoir could be expected to hold over 7 billion gallons. The Herald also noted that an inspection of the pump station was due to be made on the evening of September 1 and anticipated that "the 20,000,000 gallon pumping engine will be installed late in October or early in November."

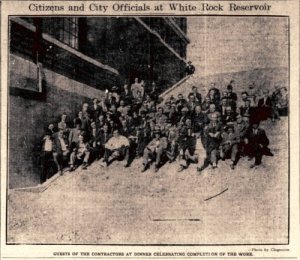

On September 22, 1911 Dallas city commissioners formally "accepted White Rock reservoir and ordered paid the final payment of $54,573.10" to the Fred A. Jones Company, bringing the total to "$285,124.03," which was a little more than $25,000 over the original estimate of $260,000. The Dallas Morning News reported that the total spent on the entire project, including "land, pumping station, connecting mains, dam and spillway," was approximately $750,000. To mark the official completion of the dam, Fred A. Jones hosted a luncheon on the afternoon of Saturday, October 7, 1911 for one hundred and forty-three businessmen, civic leaders, and journalists. Accompanied by numerous speeches, fried chicken was served in a large tent erected beside the dam and pump station. The guest list read like a veritable "Who's Who" of Dallas society. Among the dignitaries attending were William Meredith Holland--Dallas' then-current and first native-born mayor, as well as former Mayor Hay, under whose administration the project began. Journalists included Dallas Morning News editor George B. Dealey and Daily Times Herald editor Edwin J. Kiest. Prominent retailer Alex Sanger was also in attendance, along with fellow retailer Edward Titche, wealthy cattleman Christopher Columbus Slaughter, banker Edward O. Tenison, and many others.

On September 22, 1911 Dallas city commissioners formally "accepted White Rock reservoir and ordered paid the final payment of $54,573.10" to the Fred A. Jones Company, bringing the total to "$285,124.03," which was a little more than $25,000 over the original estimate of $260,000. The Dallas Morning News reported that the total spent on the entire project, including "land, pumping station, connecting mains, dam and spillway," was approximately $750,000. To mark the official completion of the dam, Fred A. Jones hosted a luncheon on the afternoon of Saturday, October 7, 1911 for one hundred and forty-three businessmen, civic leaders, and journalists. Accompanied by numerous speeches, fried chicken was served in a large tent erected beside the dam and pump station. The guest list read like a veritable "Who's Who" of Dallas society. Among the dignitaries attending were William Meredith Holland--Dallas' then-current and first native-born mayor, as well as former Mayor Hay, under whose administration the project began. Journalists included Dallas Morning News editor George B. Dealey and Daily Times Herald editor Edwin J. Kiest. Prominent retailer Alex Sanger was also in attendance, along with fellow retailer Edward Titche, wealthy cattleman Christopher Columbus Slaughter, banker Edward O. Tenison, and many others.

If any of the workmen who constructed the dam were invited to the dinner, it was not mentioned in the papers.

|

Fred A. Jones, Building Contractor Fred Atwood Jones was born in Dallas in 1875 but raised in Bonham, Texas. In 1894 he earned a B.A. from Richmond College and in 1898 a degree in electrical and mechanical engineering from Cornell. Afterward, "came miscellanous engineering and surveying in north Texas." Between 1902 and 1907 he worked as a consulting engineer until he founded his own firm. In addition to the White Rock dam, Jones' company "built the Dallas-Sherman Interurban, two state railroads, a number of power stations, [and] irrigation plants." Before he died at age 53 in 1928, Jones also constructed the Dallas Municipal Building on Harwood Street, the SMU administration buildling, the Dallas Country Club, the Southland Life Building, and the pump station at Turtle Creek. At the time of his death, he was an advisor to the Roosevelt Dam project in Arizona. |

The amicable relationship between Jones and the City Commissioners during the dam's construction was a recurrent theme in several of the speeches that were given that day. One speaker also proudly pointed out "the whole project was conceived and executed entirely by Texas people." Alluding to the drought that prompted the dam's construction, former Mayor Hay remarked, "This is indeed a very gratifying occasion, for I had become skeptical as to whether there was enough water in the world to supply all of it, but now I know that it has not been properly distributed, and so we have prepared here to take care of our part of it and save it when it is distributed again. When it does come, we are going to hold it and have enough to run Dallas for a while."

|

|

During construction of the dam, city crews had leveled many of the trees that lined White Rock creek and removed "all matter possible which would tend to pollute the water." This work included the removal of three bridges that crossed White Rock Creek at various points and also the rerouting of several roads. Altogether, the cost of clearing the creek bottom was nearly $10,000. (Another $3,476.65 was spent on "extra work.") Among the day's orators was Mike Murphy, official woodcutter for the City of Dallas, who had overseen much of that task. Echoing Hays' sentiments, Murphy predicted that as soon as the rains came not only would Dallas' water problem be solved but also that there would be "some to spare for Fort Worth."

Although there were some who believed that Dallas' water supply was now assured for at least a century, Water Commissioner R. R. Nelms was much closer to the mark when he predicted in 1911, "there will be no more water question for twenty-five years."

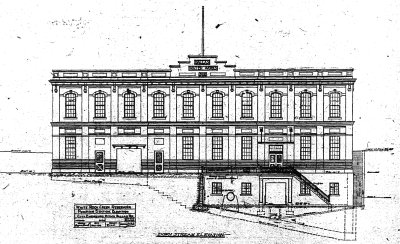

The White Rock reservoir pump house, still in use today by Dallas Water Utilities (although not for its original purpose), was also constructed in 1911. Measuring 116 feet in length and 48 feet in width, the four-story-high, red brick structure was built in the Renaissance Revival style. Decorated with terra cotta embellishments, it is located at the northern end of the dam. In a vast room that is now a huge, empty space, a triple expansion pump with a daily capacity of 20 million gallons was installed. Three large boilers, with sufficient power to drive two pumps of that size, also occupied this space. They were fired by coal brought to the pump house by train, on a spur of the KATY railroad that crossed present-day Lily Pad Bay and T.P. Hill. Concrete piers that elevated the tracks can still be seen in front of the building. Vines now cover these piers.

The White Rock reservoir pump house, still in use today by Dallas Water Utilities (although not for its original purpose), was also constructed in 1911. Measuring 116 feet in length and 48 feet in width, the four-story-high, red brick structure was built in the Renaissance Revival style. Decorated with terra cotta embellishments, it is located at the northern end of the dam. In a vast room that is now a huge, empty space, a triple expansion pump with a daily capacity of 20 million gallons was installed. Three large boilers, with sufficient power to drive two pumps of that size, also occupied this space. They were fired by coal brought to the pump house by train, on a spur of the KATY railroad that crossed present-day Lily Pad Bay and T.P. Hill. Concrete piers that elevated the tracks can still be seen in front of the building. Vines now cover these piers.

About 150 feet out in the reservoir, a steel tower "with a 6 foot square tunnel leading to the pumps" was constructed to serve as a water intake. The pump house was "connected to the city mains by a 36-inch main and 60 ft. standpipe" measuring 16, 701 feet in length.

As White Rock Lake slowly filled, curious Dallasites flocked to see this engineering marvel. At that time (and for several decades afterward), a trip to White Rock Lake was a day's outing. With Dallas being much smaller in size than it is today, the lake was literally "out in the country," on the edge of town. To reach it, people came by carriage, both horse-drawn and horseless, and were encouraged to cross the dam, so as to pack it down and settle the earth of which it was made.

About 150 feet out in the reservoir, a steel tower "with a 6 foot square tunnel leading to the pumps" was constructed to serve as a water intake. The pump house was "connected to the city mains by a 36-inch main and 60 ft. standpipe" measuring 16, 701 feet in length.

As White Rock Lake slowly filled, curious Dallasites flocked to see this engineering marvel. At that time (and for several decades afterward), a trip to White Rock Lake was a day's outing. With Dallas being much smaller in size than it is today, the lake was literally "out in the country," on the edge of town. To reach it, people came by carriage, both horse-drawn and horseless, and were encouraged to cross the dam, so as to pack it down and settle the earth of which it was made.

On Monday, April 27, 1914, a late spring downpour allowed Water Commissioner Nelms to announce that the lake had finally reached capacity. With water "at about fourteen inches over the spillway," he enthusiastically declared: "We now have six billion gallons of water stored in White Rock Reservoir…enough to supply us for two years at least." Assuring Dallasites that "in a very few days" they would be "receiving pure, filtered and softened water at their residences," Nelms humorously added that they could look forward to a summer free of "'mud baths' of city water" and concluded with the news that a "big public opening of the filtration plant [at Turtle Creek]" could be expected as soon as the city added some "little touches" to the building and "had it looking nice." (Note: The White Rock filtration plant was not constructed until the early 1920s.)

Sometime shortly after the completion of the dam, French-born Dallas photographer Henry (or Henri) Clogenson, photographed the newly-constructed dam. In the foreground of the photo is a man in an automobile, who is supposed to be Fred A. Jones. To view a larger version of this photos, you are invited to Take a Look at My Dam Picture!

Picture credits

Contemporary photo of White Rock dam by the author.

Photo of Alice Butler and friend in boats at Bachman's Lake: Personal collection of the author.

White Rock Creek Reservoir Site map: Dallas Morning News, March 21, 1909.

Photo of J. M. Preston: Dallas Daily Times Herald, October 16, 1910.

Photo of W. Barclay Parsons: Wikipedia.

Bid Advertisement: Dallas Morning News, January 23, 1910.

White Rock dam workers and derrick: Dallas Municipal Archives.

Dam Completion Banquet guests photo: Dallas Morning News, Oct. 16, 1911.

Fred A. Jones portrait: Standard History of Houston, Texas (Knoxille, Tennessee: H.W. Crew & Co., 1912), 403.

George B. Dealey photo: Ted Dealey's Diaper Days of Dallas (Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, 1966), inset.

Pump House specifications: Dallas Morning News, Oct. 13, 1910.

Drawing of couple in horseless carriage: Dallas Daily Times Herald, circa 1903.

Dam photo by Henry Clogenson: Courtesy Eliot Greene.

This website copyright © 1996-2011 by Steven Butler, Ph.D. All rights reserved.